In antebellum Liberty County, Georgia — amongst some of the wealthiest slaveowners of the time — Henrietta (“Hetty”) Hamilton, a free woman of color born at the end of the 18th century, lived independently on 50 acres of land given her as a “life estate” by a wealthy white planter and slaveholder named Jacob Wood. When he sold the land, he conditioned the sale on continuation of her life estate. Henrietta Hamilton herself also held at least 12 African Americans enslaved during her lifetime before her death in 1868.

Who was Henrietta Hamilton? How did she come to this position, and what happened to her after the Civil War? Let’s look first at what we know to be true about her from the records, then at what can be conjectured.

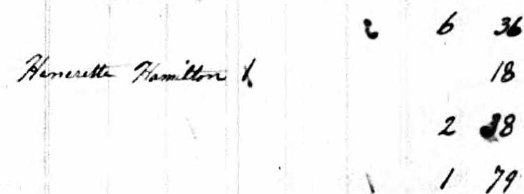

The first mention of Hetty Hamilton found in the records was in the 1830 U.S. federal census for Liberty County, when she was listed by name as a free woman of color between 36-55 years old in the entry for Jacob Wood, who was the only white person in his household. He was also listed with 17 enslaved people: eight men and nine women. She was the only free person of color listed by full name in the 1830 Liberty County census.

To give an idea of how unusual this was, in 1830 Liberty County had the following population statistics:

White Males — 784

White Females — 804

Male Slaves — 2789

Female Slaves — 2836

Free Man of Color — 8

Free Women of Color — 13

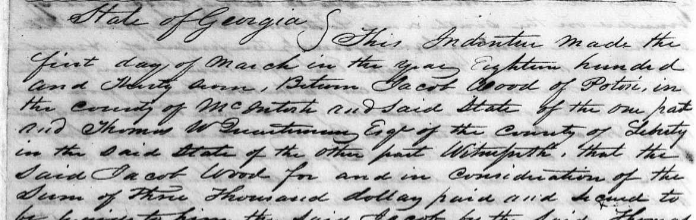

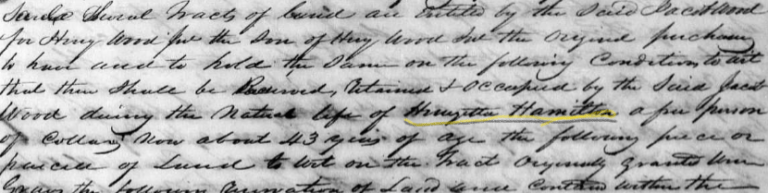

In 1837, Jacob Wood, who had by then moved from Liberty County to Potosi, McIntosh County, sold several tracts of land in Liberty County to Thomas W. Quarterman for $3,000, on the condition that Quarterman honor the “life estate” granted to “Henrietta Hamilton a free person of color now about 43 years of age.” The deed said that the land had originally been granted to William Graves, and gave a detailed description of the boundaries. Wood specified that whomever he allowed to live there (Hamilton) would have the right to cut as much timber as needed for personal use from the nearest and best wood land without obstruction by Quarterman during her life estate.

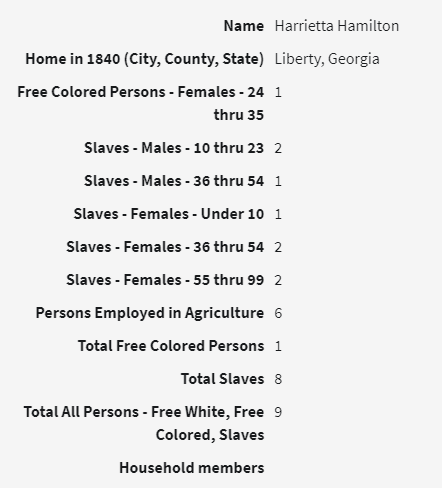

After Jacob Wood moved to McIntosh County, Henrietta Hamilton then received her own entry in the 1840 census, and was listed as owning eight enslaved people: 2 boys 10-23 years old; 1 man 36-54; 1 girl less than 10, 2 women 36-54, and 2 women 55-99 years old. Could one of those have been her mother?

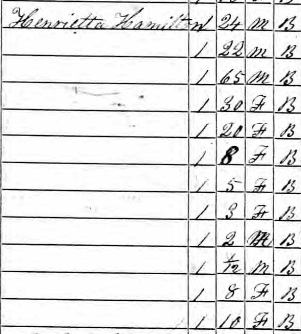

The 1850 census gave further details: she was a free mulatto woman born in South Carolina, living in her own household. In 1850, the “slave schedule” was a separate document, and Henrietta Hamilton was listed with the white slaveholders, now owning a 24-year-old man, 1 22-year-old man, 1 65-year-old man, 1 30-year-old woman, 1 20-year-old woman, one 8-year-old girl, 1 5-year-old girl, 1 3-year-old girl, 1 2-year-old boy, 1 8-month-old boy, 1 8-year-old girl, and 1 10-year-old girl. Were they her relatives? The census is silent on that point.

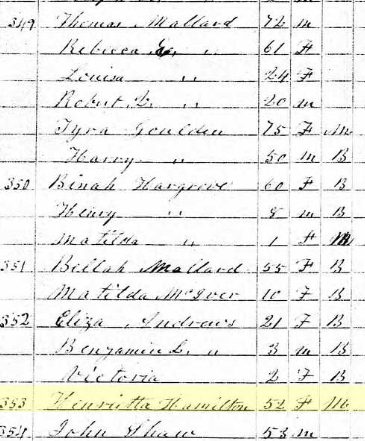

In 1850, Henrietta Hamilton was living within a little cluster of free people of color living near or on land of white Liberty County planter Thomas Mallard. This included Tyra Gaulden, a 75-year-old mulatto woman, and Harry Gaulden, a 50-year-old black man, who were listed within Mallard’s household. Nearby were Binah Hargrove, a 50-year-old black woman who had been manumitted by her previous owner Joseph Hargreaves — also the acknowledged father of her child Shadrach, who had been sent to live in England with Hargreaves’ nephew. Binah was living with Henry Hargrove, 8 years old, and Matilda Hargrove, one year old — perhaps her grandchildren? Matilda was described as mulatto. They were near Bellah Mallard, a 55-year-old black woman, and Matilda McIver, a 10-year-old black girl, listed together, and the household of Eliza Andrews, a 21-year-old black woman, Benjamin L. Andrews, a 3-year-old black boy, and Victoria Andrews, a 2-year-old black girl.

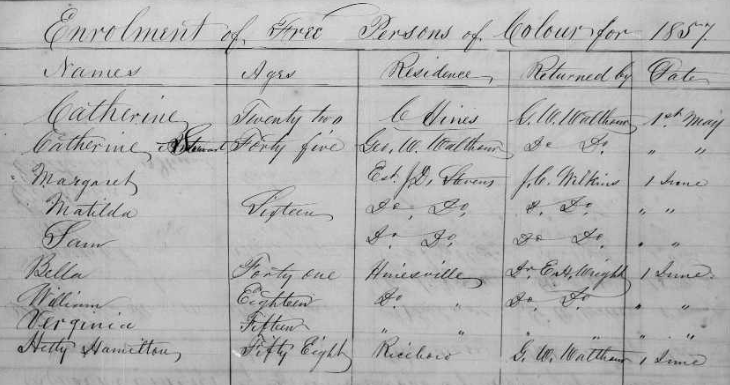

In Georgia after 1819, free people of color had to register annually and have a white “sponsor.” The Liberty County records for this from 1852 to 1864 have survived. In 1852, Hetty Hamilton was listed as a 53-year-old woman living in Riceboro, sponsored by George W. Walthour, one of the wealthiest landowners and slaveholders in Liberty County, whose family name had been given to the city of Walthourville. He continued as her sponsor until 1859. She does not appear in the records after that, but something may have changed in the registry requirements after 1860, because only two people are listed after that.

In 1857, Thomas W. Quarterman of Liberty County, Georgia — honoring his contract with Jacob Wood — noted in his will that Hetty Hamilton, a free woman of color, was living on a 50-acre tract of land within his 450-acre “Wood tract” that was to be hers until she died.

Henrietta Hamilton was not listed in the 1860 census or slave schedule. The reason for this is not known, since in 1857 she was still living on her life estate on the land that had belonged to Wood.

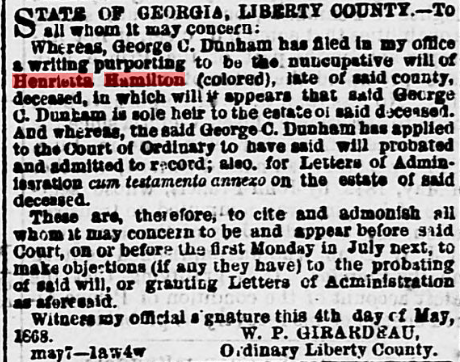

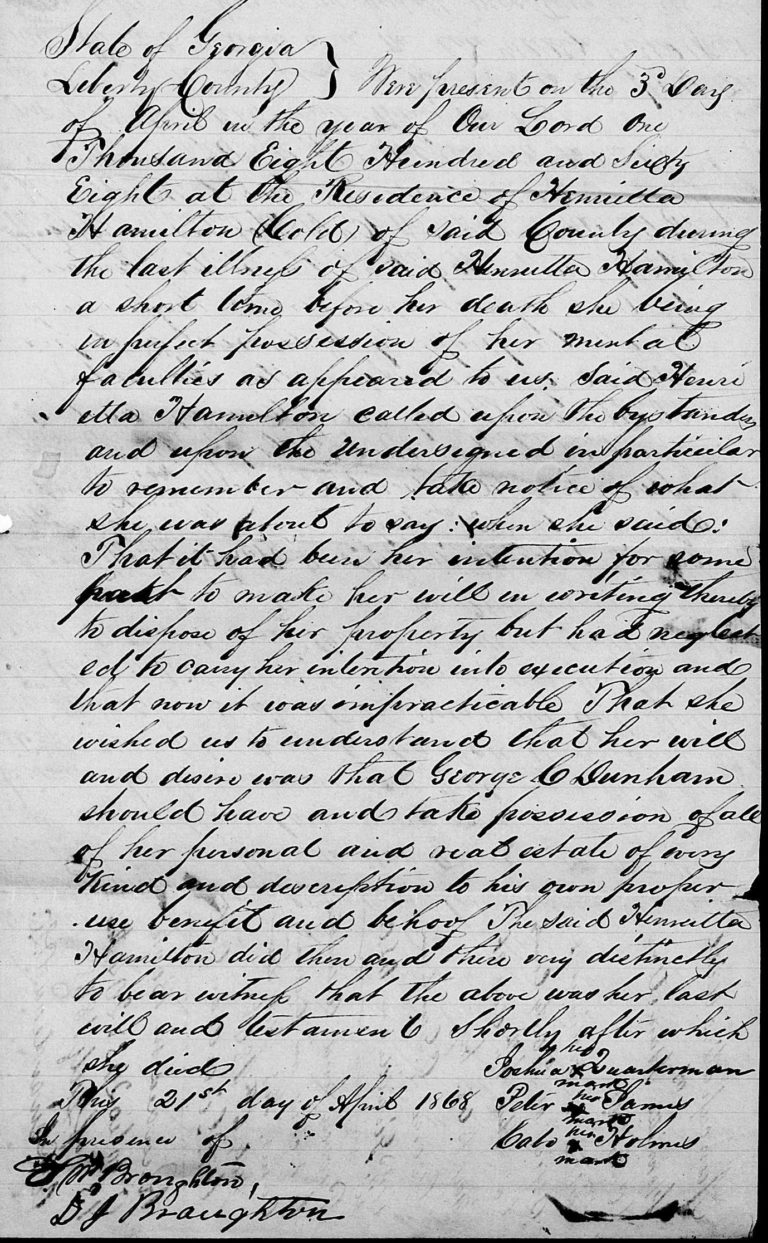

She died at home on April 3, 1868, surrounded by people. She told three of them — formerly enslaved men Joshua Quarterman, Peter James, and Cato Holmes — that she wanted to leave all her possessions to George C. Dunham. This was called a noncupative (oral) will, and it was recorded in Liberty County probate court, and advertised in a Savannah paper, as required by law.

The men at Henrietta’s bedside were listed in the 1870 census: Joshua Quarterman, about 73, Cato Holmes, about 52, Peter James, about 52.

Now for the conjecture, based on facts that came to light during this research.

How did Henrietta come to be free? She could either have been born free to a free mother, or she could have been manumitted. No record was found of her manumission but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Given that she was identified as mulatto, it is most likely that she was the child of a white man and an African American woman born, according to the various records, between 1794 and 1798.

Jacob Wood, the most likely “suspect” to be her father, was born in 1768 in Pennsylvania. His father, Joseph Wood, moved to Georgia around 1774, tried unsuccessfully to get Georgia to join the American Revolution, and returned to Pennsylvania to fight, becoming a full colonel in the Continental Army at the time. When he returned to Georgia this time, he was named a delegate to the Continental Congress and was elected again in 1778. Joseph Wood died at his plantation near Riceboro in Liberty County in 1791, survived by his wife and four children. He and his children were members of Liberty County’s Midway Congregational Church.

His son Henry became the Sheriff of Liberty County and frequently participated in the sale of enslaved men, women and children whose enslavers had lost them to a legal judgement. Wood would seize the enslaved people from their home, put them up for auction at the courthouse, and handle the paperwork to transfer them to the highest bidder. Henry Wood owned at least 40 enslaved people when he died in 1802: Tom, Penda, Monday, Rachel, Sylvia, Caesar, Sancho, Brutus, Elcey, Marcus, Ben, Osmond, Lucy, Ned, Sam, Caesar, George, Charles, Bob, Peter, Hector, Patty and her daughter Chloe, Jeator, Fanny, Betty and her daughter Lucy, Prince, Mira, Hannah and her daughters Betty and Jeany, Harry, Hosey, Peter, Charles, Scipio, Will, Charlotte, Flora, Ben, and Tenah.

Jacob, the son associated with Henrietta Hamilton, lived in Liberty County through his early life, then owned land in McIntosh County, at Potosi Island, just west of Darien, and married a member of an elite McIntosh County family: Elizabeth Jane Brailsford, daughter of William and Maria (Heyward) Brailsford, who died the same year they were married, 1807. Jacob had one daughter, from his previous marriage to Sarah Sanders Smith.

Given his father’s connections, Jacob’s life took an unsurprising trajectory. He was a senator from McIntosh County in the Georgia Legislature and President of the Georgia Senate (1833-34); a judge in McIntosh County’s Inferior Court; and well known and connected across elite white planting families in coastal Georgia. He also was a trustee of Franklin College, which later became part of the University of Georgia, and a founder of the Bank of Darien. In 1820, he owned 104 enslaved people in McIntosh County. In 1830, when he was listed at his property in Liberty County, he was holding 17 people enslaved…and had Hetty Hamilton, free woman of color, living in his household or on his land.

As evidenced by his 1844 will, Jacob Wood did have a surprising interest, however. Florida planter and slaveholder Zephaniah Kingsley, a Quaker born in England who had moved with his family to South Carolina, then later to Florida, believed in interracial relationships, practiced polygamy with the women he was holding enslaved, and allowed his enslaved people to purchase their freedom.

Kingsley reportedly had nine mixed-race children, and no white children. After Florida transferred to American rule, Kingsley established his mixed-race son, George Kingsley, in a plantation in Haiti and transferred some of his enslaved people there in indentured servitude. After his death in 1843, his white relatives fought their mixed-race cousins’ inheritance but lost.

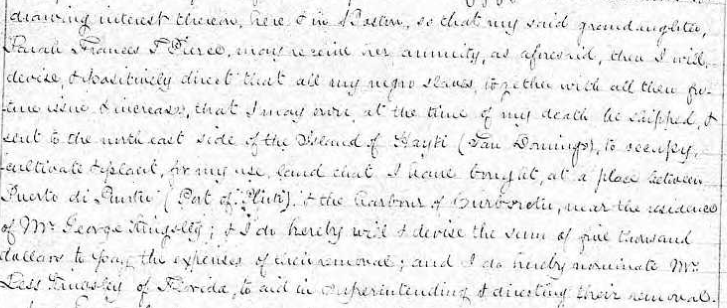

In Jacob Wood’s will, he directed his executors to build up a trust amount of $50,000 to pay for his granddaughter Sarah Frances P. Pierce’s education and maintenance, and if necessary, to put the enslaved people he owned to work on his land on Big Creek in Pulaski and Dooly Counties in Georgia until the amount was earned.

Once the trust money was raised, however, all the enslaved people he still owned at the time of his death were to be shipped to the northeast side of Haiti to land he had bought near the home of George Kingsley, Zephaniah Kingsley’s son. He set aside $5,000 to pay for their move and asked that Zephaniah Kingsley aid in supervising it.

However, Wood apparently had not realized that Zephaniah Kingsley had died in 1843, so was not available to help with the move, and the enslaved people wound up becoming free and moving to Liberia instead. Their fate is beyond the scope of this article, and their names have been transcribed separately.

Why did Wood’s will not include Hetty Hamilton? Did he feel he had already provided for her by ensuring she had a life estate on the land he sold to Thomas W. Quarterman? For a man who appeared deeply committed to Zephaniah Kingsley’s experiment, it seems odd that he did not at least leave her money in the will if he was in fact related to her.

That questions brings us to the elephant in the room. Why did Henrietta have the surname Hamilton? And why was she said to have been born in South Carolina, when it does not appear that Wood had connections there? Where was she before she appeared in the 1830 census in Wood’s household? She was not listed with him in the 1820 census.

The possible answer may be the most surprising twist in Henrietta Hamilton’s remarkable life. No one with the surname Hamilton was found in a search of the Liberty County deed records for this period, but Liberty County Sheriff Henry Wood sold court-confiscated land to the firm of Couper & Hamilton, one of whose directors, John Couper (1759-1850), did live in Liberty County before he moved to Glynn County.

Couper married Rebecca Maxwell in Liberty County, and his son James Hamilton Couper was born in 1794 in Sunbury, Liberty County. John Couper named his son James Hamilton Couper after his close friend and partner, James Hamilton (1763-1829). On St Simons Island in Glynn County, Couper owned the Cannons Point plantation, and James Hamilton the Hamilton plantation, a portion of which was called Gascoigne’s Bluff, where a few of the original tabby slave dwellings still stand.

James Hamilton was born in Scotland in 1763, and moved to the United States in 1784, where he became a merchant in Charleston, South Carolina. He maintained a residence there but also purchased his St. Simons Island plantation in 1800, and co-owned with John Couper the Hopeton (now Altama) Plantation near Darien, McIntosh County, Georgia, which they bought in 1805. James Hamilton was a very wealthy man who eventually sold his properties, mostly to his namesake, James Hamilton Couper, and moved to Philadephia by 1820. Those interested in coastal Georgia history will recognize these names as being of the elite of their time.

What about Hetty Hamilton’s life makes more sense if we explore the possibility that James Hamilton was her father? Certainly, the Hamilton surname and her birth in South Carolina. What about the lack of records of her presence in Liberty County before 1830? In the 1820 census, James Hamilton was listed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In his household were one white boy, 10-15 years old, one white man over 45, one white girl 16-25 years old, and one white woman 26-44. These may have been his son George, born in 1806, himself, his daughter Agnes Rebecca Hamilton. One record said his wife had died by 1818, so this was either some other woman, probably a relative, or the record was mistaken.

Also listed were free people of color: one man 26-44 years old, two girls under 14, and one woman 26-44. Hetty would have been about 22 to 28 in 1820. Given the vagaries of birth records of the time, it is possible this was her. It was certainly unusual that Hamilton had free people of color living with him.

If Hetty was James Hamilton’s daughter, why would she have shown up in Liberty County in the 1830 census, living with Jacob Wood? James Hamilton died in April 1829. His will divided his estate among his white heirs, and it took more than 40 years for his affairs to be sorted out. It would make sense that either by arrangement before his death or after his death, Hetty would have been sent to a trusted friend, given that his white heirs were probably little interested in her. We know that Jacob Wood had sympathies with a man, Zephaniah Kingsley, who advocated interracial marriages and relationships, caring for one’s interracial children, and manumission. Wood was also a widower, and prominent enough not to care what others thought.

Although James Hamilton apparently did not live in Liberty County, he likely had visited his friend and business partner John Couper there frequently before Couper’s move to Glynn County in the early 1800s, especially because Couper & Hamilton had bought land in Liberty County. He and Couper would also have known the Wood family well, both because of their business dealings with Sheriff Henry Wood, and because of Jacob Wood’s prominence as a planter and a legislator in McIntosh County, and the proximity to the Hopeton (now Altama) plantation purchased by Couper & Hamilton in 1805.

When in 1837 Jacob Wood decided to sell his Liberty County land to Thomas W. Quarterman, a white land- and slaveowner, Wood described himself as being of McIntosh County, living at Potosi, and sold to Quarterman for $3000 several tracts of land. As mentioned earlier, a condition of the sale was that fifty acres of one of the tracts was to be allowed to be “occupied by the said Jacob Wood during the natural life of Henrietta Hamilton a free person of collar now about 43 years of age.”

Quarterman evidently accepted and honored the contract. When he died, in 1857, his will stipulated that his son Robert Y. Quarterman was to receive “my Wood tract of land adjoining my NewPort plantation divided from it by and lying east of, the Barrington road, containing four hundred and fifty acres more or less, including a fifty acre tract upon which Hetty Hamilton, a free person of colour [color], now lives and which at her death reverts to me…”

If the hypothesis holds that Henrietta was Hamilton’s daughter, and that Wood allowed her to live on his land after Hamilton’s 1829 death, whether out of friendship or some other motivation, it would make sense that he would make provision for her during the sale of the land, but not in his own will.

However, it is evident that James Hamilton did not provide for Henrietta in his own will. Contrast this with the treatment of his white daughter from his London-born wife. Agnes Rebecca Hamilton (1801-1894) married Francis Porteus Corbin. She was wealthy, due to her inheritance from her father, and she and Corbin moved to Paris, where two of their daughters married into the French nobility. Elizabeth married the Vicomte de Dampierre; Isabella married the Marquis de Montmort. Interesting to think that if James Hamilton were in fact Henrietta Hamilton’s father, she was related to the French nobility.

Henrietta Hamilton’s life story deserves to be told, whatever the connection with these wealthy white men, but exploring the connections, and possible connections, reveals perhaps unexpected complexity in coastal Georgia social attitudes towards race, status, and slavery.

The search in this article has been for Henrietta’s father. However, it is certainly possibly that she had a different relationship with any of the wealthy white men who took this documented interest in her, despite the age differences, given that they would have considered they had a right to exploit her in whatever way they chose.

Where might the answer to Henrietta Hamilton’s origins lie? James Hamilton’s letters, business documents, and personal records are held at several institutions, including Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. A thorough search of these records may turn up the answer.

Research Sources:

Jacob Wood, John Couper, and James Hamilton were well known historical figures, and details about their lives and their families are readily available in online repositories, including Google Books, Wikipedia, and Ancestry.com. “Early Days on the Georgia Tidewater: The Story of McIntosh County & Sapelo,” by Buddy Sullivan was also very helpful.

For more information about Zephaniah Kingsley, see Mark J. Fleszar’s works “The Atlantic Legacies of Zephaniah Kingsley: Benevolence, Bondage, and Proslavery Fictions in the Age of Emancipation” and “The Atlantic Mind: Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World.” Fleszar refers to extensive correspondence between James Hamilton and Zephaniah Kingsley contained in Hamilton’s papers.

Documented Sources:

1830 Census showing Henrietta Hamilton in Jacob Wood’s household:

1830 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, alphabetical order, Jacob Wood household, Series: M19; Roll: 19; Page: 54; Family History Library Film: 0007039; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed 6/13/2021, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8058/images/4409522_00106?pId=1850237).

1837 Sale of Land by Jacob Wood to Thomas W. Quarterman

Liberty County Superior Court, “Deeds & Mortgages v. K 1831-1838 ,” p. 447-9, Jacob Wood to Thomas W. Quarterman; digital image, FamilySearch.org, “Deeds & Mortgages, K-L 1831-1842 ” within “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” image #276-7, (accessed on 6/13/2021 at https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T9KV-R?cat=292358)

1840 Census showing Henrietta Hamilton in own household with enslaved people

1840 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Roll: 45; Page: 192; Family History Library Film: 0007045, Henrietta Hamilton household, digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8057/images/4411334_00396?pId=1791421, accessed 6/13/2021)

1850 Census showing Henrietta Hamilton in own household and living in cluster of free people of color:

1850 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, District 15; Roll: 75; Page: 331a; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8054/images/4193244-00398?pId=18776351, accessed 6/13/2021)

1850 Slave Schedule

1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules Record, District 15, Liberty County, Georgia, enumerated October 4, 1850 by john Shaw. Digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8055/images/GAM432_92-0292?pId=92523506, accessed 6/13/2021)

Liberty County Free People of Color Registry, 1852-1864: https://theyhadnames.net/2019/04/05/free-persons-of-color-1852-1864/

Transcript and sourcing for 1857 Thomas W. Quarterman will: https://theyhadnames.net/2018/05/09/liberty-county-will-thomas-quarterman-2/

1868 probate documents for Henrietta Hamilton

“Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9QW-7QKK?cc=1999178&wc=9SBJ-K6D%3A267679901%2C268030501 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills 1925-1957 Deen, Thomas-Miller, E. C. > image 350 of 1300.

Jacob Woods 1844 will

Suffolk County (Massachusetts) Probate Records, 1636-1899; Author: Massachusetts. Probate Court (Suffolk County); Probate Place: Suffolk, Massachusetts; digital image in “Massachusetts, U.S. Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 -> Suffolk -> Probate Records, Vol 147, 1848-1849,” image 135 Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9069/images/007703195_00135?pId=580475, accessed 6/13/2021). See transcript of the will at: https://theyhadnames.net/2021/06/14/mcintosh-county-will-jacob-wood/.

1820 James Hamilton census

1820 U.S. Census, Philadelphia Pennsylvania, population schedule, alphabetical order, James Hamilton household, Census Place: Philadelphia Locust Ward, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; NARA Roll: M33_108; Image: 063; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed 6/13/2021, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7734/images/4433234_00063?pId=1503662).

1829 James Hamilton will

Ancestry.com. New York, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

Original data:New York County, District and Probate Courts. Digital Image (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8800/images/005518067_00103?pId=842218, accessed 6/13/2021)

1868 newspaper clipping

The Daily News and Herald, Savannah, Georgia, May 7, 1868. Courtesy of the Digital Library of Georgia, Georgia Historic Newspapers.