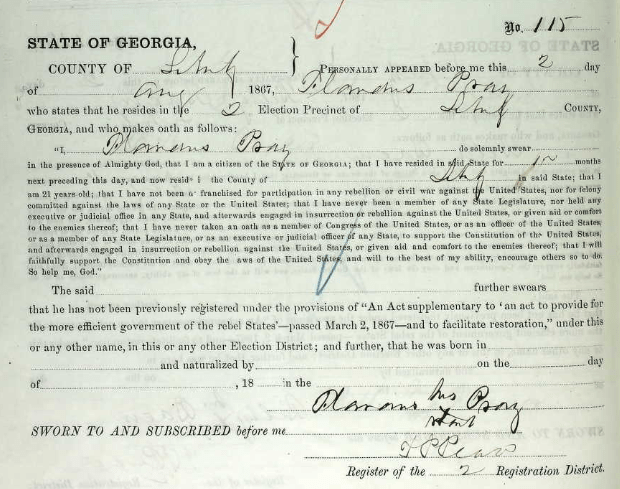

Flanders Pray registered to vote for the first time in his life at the age of 30, on August 2, 1867. He registered in Hinesville, Liberty County, in the 2d Election District.[1] From birth until only two years earlier, he had been held as a slave, legally forbidden to learn to read. Two years later, he became a schoolteacher. One might say he “became” a leader in his community, but the likelihood is that he was a leader all along, just without the records of it that came to exist after Emancipation.

Leadership Roles

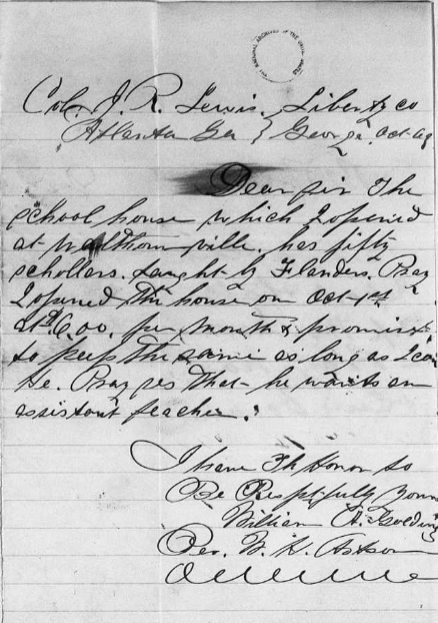

He clearly must have already been literate when Emancipation came. William A. Golding hand-picked him to head a school for freed people in Walthourville in 1869[2]. Golding opened the school on October 1, 1869, with 50 pupils and reported that Mr. Pray was paid $6.00 per month and wanted an assistant teacher.

That year Mr. Pray was a founding member of the Baconton Missionary Baptist Church: “In 1869, a God-fearing group, led by founding pastor Reverend W.M. Quarterman, five deacons (Will Bacon, Joe Howell, P.M. McIver, Flanders Pray Sr., Julius Rogers), and thirty-five members, desired a church and a school, possibly named for Will Bacon, under a bush arbor and a framed structure was completed later in 1876. The Baconton School, supported by the Freedmen’s Bureau and the community, was a two-room wooden schoolhouse on the church property, Flanders Pray Sr., was the first teacher.”[3]

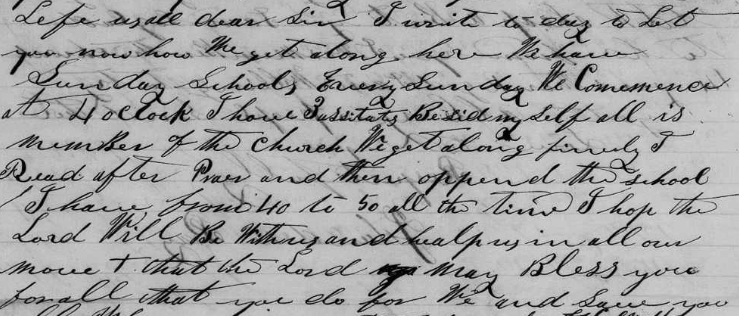

In a March 1870 letter, Mr. Pray reported to the American Missionary Association, which was funding the school, that “here we have Sunday Schools every Sunday. We commence at 4 o’clock. I have 3 assistants beside myself, all is members of the church…I have from 40 to 50 all the time. I hope the Lord will be witness and help us in all…The day school will stop after March but the night school will go on.” He added that the day school had had to stop because the children were needed for planting.

The Freedmen’s Bureau reported that his school was supported by the American Missionary Association and gave the number of his students for the period from October 1869 to June 1870[4]. (The period ended for all the schools that summer of 1870, likely showing the end of Bureau support, not the end of Pray’s work.)

|

Oct ‘69 |

Nov ‘69 |

Dec ‘69 |

Jan ‘70 |

Feb ‘70 |

Mar ‘70 |

Apr ‘70 |

May ‘70 |

June ‘70 |

|

27 |

27 |

57 |

54 |

57 |

41 |

44 |

47 |

24 |

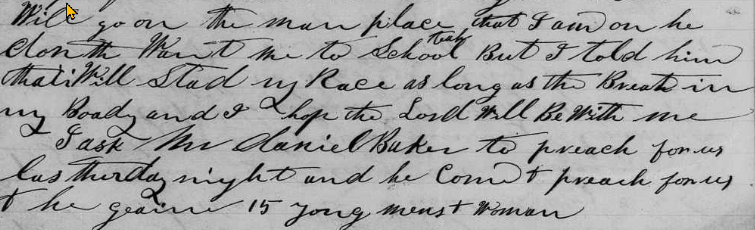

The new freed people’s schools had the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau and organizations such as the American Missionary Association, but the remaining White power structure within the County continued to resist the new order. In that same March 1870 letter, Mr. Pray reported, “The man[‘s] place that I am on he don’t want me to teach school but I told him that I will [word] my race as long as the breath [is] in my body and I hope the Lord will be with me.” He added that he had asked Daniel Baker to preach recently and that the sermon gained 15 young men and women.

William A. Golding had already reported to the Freedmen’s Bureau in November 1869 that “a Methodist Preacher told him [Flanders Pray] that if he don’t close his school they will whip him to death that they wont be intruded on by nigras teaching.”[5]

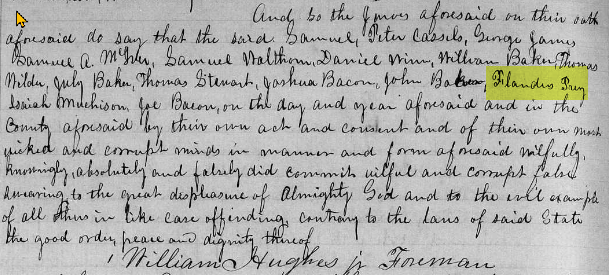

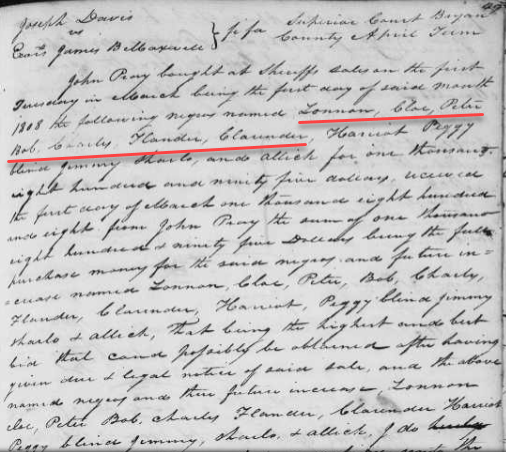

Mr. Pray’s leadership and resistance extended into the political realm. Liberty County since its founding had been a majority African American community, but that community was not able to exercise political power until after Emancipation. In the short period of Reconstruction, Flanders Pray was a leader in this effort. In November 1868, White court officials attempted to suppress the Black vote by refusing to open the Riceboro precinct polling place. Black leaders opened the polling place anyway and many Black voters, including Flanders Pray, voted. Their votes were not counted, and the Black voters, including Mr. Pray, were indicted by the Liberty County Grand Jury.[6] Nothing seems to have come of the case, but the underlying threat must have been evident.

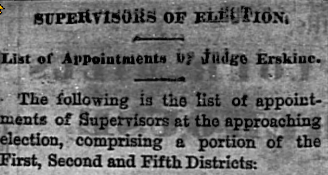

Undeterred, in 1874, Flanders Pray was appointed as the Republican Election Supervisor for Liberty County’s 16th G.M. District.[7] Each district had both a Republican and Democrat election supervisor.

In 1880, Flanders Pray was also the coroner of Liberty County[8], serving alongside White officials who had been Confederate officers.[9]

Personal Life

In the 1870 census, Flanders Pray was listed as a schoolteacher living with his wife, Affy (37), and presumably his children, Flora (13), Moses (10), Flanders (7), Carolina (3), Louisa (8 months).[10] Affy Pray probably died before 1878, when Flanders Pray married Miss Peggy Wood.

In the 1880 census, Flanders was listed as a laborer, and he and Peggy had with them their children Moses (21, employed as a laborer), Flanders J. (13, a laborer), Caroline (14, washing), Louisa (9), Sallie (7), William (3), and grandson Charles[11]. Based on the ages and the marriage date, it appears that Sallie may have been Affy’s child, born since the 1870 census, and William possibly also was Affy’s child. They were living near Abner and Annette Hargraves, Peter and Fanny Barnard, Cudjo and Ellen Norman, Richard and Renchi Barnard, and Moses and Patty Wood.

Flanders Pray does not appear to have owned land during his life[12]. However, as of 1878, he owned at least eight head of stock cattle, marked with a crop in one ear and a hole in the other, and four head of hogs.[13] By 1888, he and his wife Peggy owned a 3-year-old white heifer, which they used as security on a promissory note to James E. Hines for $10.[14]

In 1887, he and his daughter, Caroline Lee, purchased a Singer sewing machine, style C.O.L. No 3478070, on credit. To secure the loan, he mortgaged “seven (7) head of cow, marked crop in left ear, underbit and crop in right ear all on place of F. Pray and valued at seventy five dollars.”[15]

By the 1900 census, Flanders and Peggy Pray were said to have been married for 19 years, and she had had 9 children, 8 of them living[16]. He was about 64 and she was about 40. In their household were Frank (18, farm laborer), Albert (15, at school), James (13, at school), Julia (Julius) (11, at school), Patty (9), Dafney (7), Lawrence (3), and Phoebe (1). Mr. Pray was listed as a farmer.

Flanders and Peggy Pray may have both died before 1910, as five of their youngest children were found living on their own then by the census taker. Patsey Pray was listed as the head of a household that included her siblings Julius (20), Daphney (17), Laurence (13), and Phoebe (12). Rebecca Wade (25) was living with them as a boarder[17]. Unfortunately, Georgia did not start keeping death records until about 1919 so no death records were found for them.

Before Emancipation – Flanders Pray and His Family

Pray was not a common surname in Liberty County. There was only one other African American Pray in Liberty County in 1870 and no white Prays.

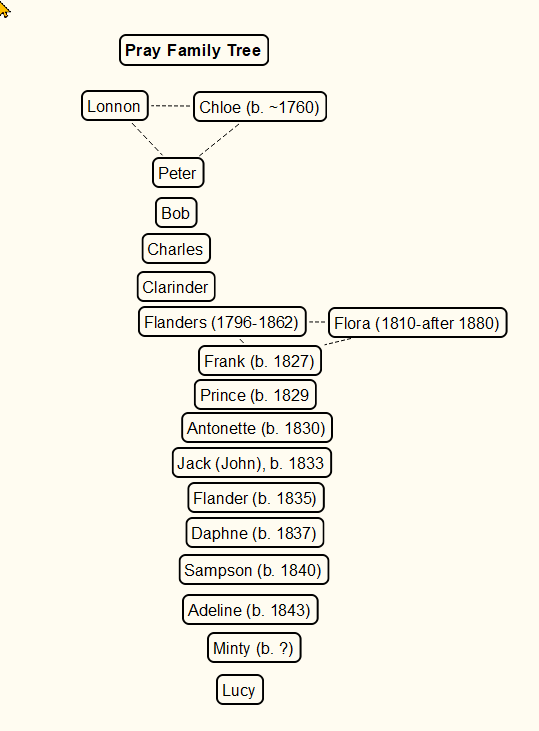

It turns out that Flanders Pray was actually from Bryan County, Georgia, which borders Liberty County. His parents were Flora and Flanders. His father’s parents were Lonnon (a version of London) and Chloe, who also had children Peter, Bob, Charles, and Clarinder. Flanders Sr was born around 1796 and died around 1862. His mother Chloe was born around 1760. Flora survived to Emancipation. Lonnon and Chloe were held in slavery by John Pray of Bryan County, who died in 1819, but were originally purchased by him from James B. Maxwell at a Sheriff’s Sale in 1808.

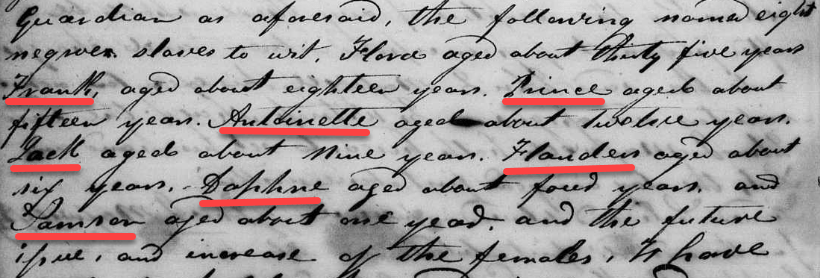

Flanders Pray’s mother Flora had at least eight other children: Frank (b. 1827), Prince (b. 1829), Antonette (b. 1830), John (Jack) (b. 1833), Daphne (b. 1837), Sampson (b. 1840 or 1841, Adeline (b. 1843), and Minty.

Flanders Pray, his parents and his siblings were held in slavery by Lewis and Mary Jane Hines, and then by Charlton Hines.

How do we know these facts? The same documents used to document the lives of their enslavers reveal at least the bare bones facts of their lives.

Timeline and Details

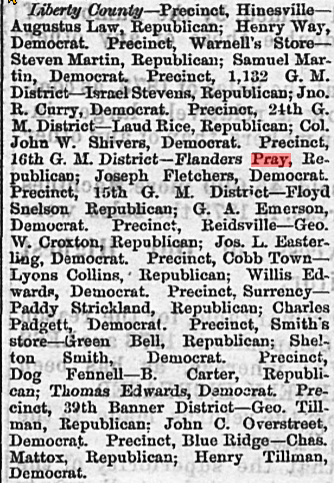

In 1808, John Pray, a white slaveowner and planter of Bryan County, purchased as a family Lonnon, his wife Cloe, and their children Peter, Bob, Charles, Flander, and Clarinder, as well as Harriot, Peggy and blind Jimmy, Sharlo, and Allick[18]. He paid $1895 for the group as the highest bidder at a Bryan County Sheriff’s Sale. They were being auctioned off as the property of James B. Maxwell’s estate based on a lawsuit against the estate in Bryan County Superior Court. Unfortunately, Bryan County probate records appear to no longer exist, so no records were found that might give more information about their history with the Maxwell family.

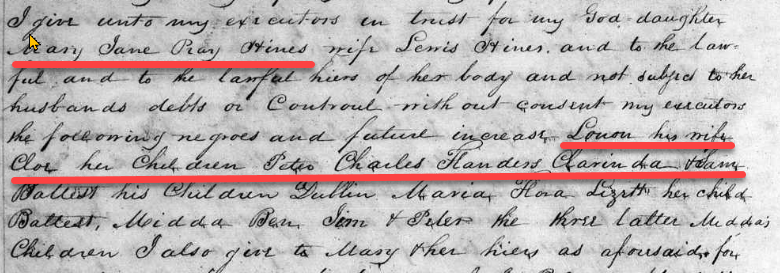

In 1819, Col. John Pray wrote his will in Chatham County.[19] He owned real estate and enslaved people in Bryan, Liberty and Wilkes Counties. He took unusual care to name the relationships of the people he was holding in slavery; most enslavers only named the relationship of mothers to young children but he named entire family groups.

John Pray did not appear to have children living at the time of his will or death, and so all his property was left to relatives and friends (mostly women). He gave to his goddaughter Mary Jane Pray Hines, wife of Lewis Hines of Bryan/Liberty County, and to her heirs, “the following negros & future increase Lonnon [alt: London] his wife Cloe her children Peter Charles Flanders Clarinder [alt: Clarinda] & Sam.” Sam appears to have been born after the 1808 Sheriff’s Sale.

This Flanders could not have been the Flanders Pray who was a teacher in Liberty County after the Civil War, as he was born in the 1830s. Thus the question arises: what relationship was this Flanders to Flanders Pray?

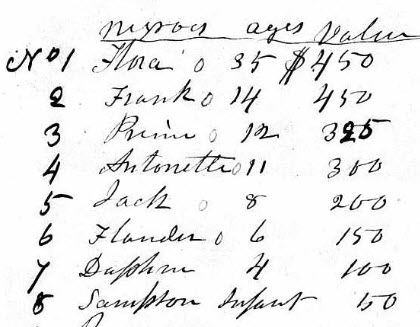

Although no records of the transfer from John Pray’s estate to Lewis Hines were found, Lewis Hines died in 1840, and we find two people by the name of Flanders in his 1841 Bryan County estate inventory, one a 6-year-old Flander at Hines’ Silk Hope Plantation[20].

The other was 45-year-old Flander, also at Silk Hope Plantation. Based on this age, he was born around 1796.

It seems very likely from this record that Flora was young Flander’s mother, and that Frank, Prince [or Prime], Antonette, Jack, Daphne and Sampson were his siblings. These children had all been born after John Pray’s 1819 will. Again we wonder: what relationship was the 45-year-old Flander to young Flander?

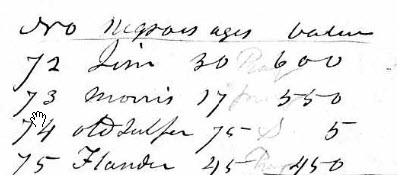

“Old Cloe”, 80 years old, and presumably Flander Senior’s mother based on the 1819 John Pray will, was listed at Bellmont Plantation. Based on this age, she was born around 1760.

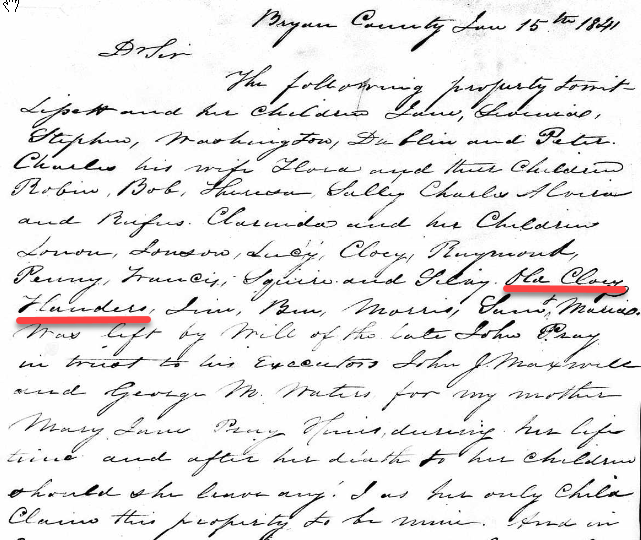

There was a family dispute over Lewis Hines’ estate. Remember that John Pray had left these enslaved people to Lewis Hines’ wife, Mary Jane Pray Hines, and after her death to her heirs. For that reason, her son, John Pray Hines, argued in court in Bryan County in 1841 that the surviving enslaved people affected by John Pray’s will should come directly to him and not be considered as part of Lewis Hines’ estate.[21] He named the following people who were affected: “Lissett and her children Jane, Lavinia, Stephen, Washington, Dublin and Peter, Charles his wife Flora and their children Robin, Bob, Theresa, Sally, Charles Alvira and Rufus, Clarinda and her children Simon, Jonson [or Johnson], Lucy, Cloey [or Chloe], Raymond, Perry, Francis, Squire and Silvy, Old Cloey, Flanders, Jim, Ben, Morris, Sam & Maria.”

Old Cloey and Flanders were clearly Flanders Senior and his mother Chloe, as Flanders Junior was not alive at the time of John Pray’s will.

John Pray Hines clearly won his suit, because in May 1842 he used the people named, including Flanders Senior, as collateral for a loan he had received from the trustees of the “Meeting House on the Neck Road near Hardwick” in Bryan County[22]. The record actually gave the ages of the enslaved people named: Clarinda (40) Lonon (18) Johnson (16) Lucy (14) Chloe (12) Reymond alt: Raymond Peney (18) Frances (16) Squire (3) Sylvia (1) Charles (45) Flora (40) Robin (19) Bob (17) Theresa (14) Sally (11) Charles (6) Elvira (4) Rufus (2) Flanders (42) Tamar (46) Darby (21) Caroline (19) Caller or Coller Cornelia (11) Hetty (4) Ben (23) Morris (20) Sam (28) John (40) Ben (45) Abby (45) William (22) Amas (17) Emmick (15) Lissett (49) Stephen (17) Washington (12) Dublin (8) Peter (5).

Although the lawsuit had only argued that he was entitled to the people inherited by his mother in 1819, in 1842 John Pray Hines also used Flanders Senior’s wife Flora and her children as collateral for a loan he received from Sophia A. Lindel, the guardian of William J. Harrison’s minor children[23]. This follows the principle, if it may be called that, that enslaved people were inherited, sold and gifted with the unborn children of the women.

The deed record provided their ages at the time: “the following named eight negroe slaves to wit, Flora aged about thirty five years, Frank, aged about eighteen years, Prince aged about fifteen years, Antoinette aged about 12 years, Jack aged about nine years, Flanders aged about six years, Daphne aged about four years and Samson aged about one year.”

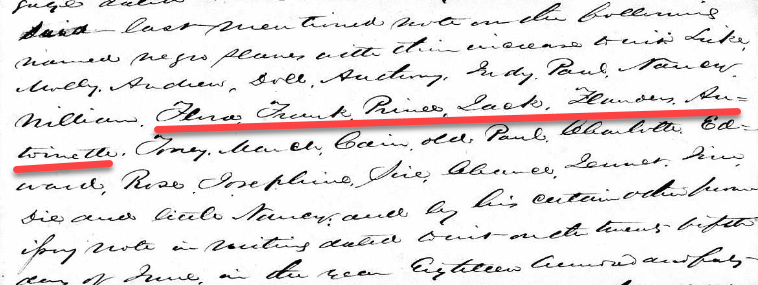

Flanders Junior was mentioned in a separate court case in 1842, when a Michael Prendergast had attempted to attach part of Lewis Hines’ estate because he said Hines had owed him money.[24] In his response, Charlton Hines, the estate’s executor, named the enslaved people who had been used as collateral for these promissory notes to Prendergast, including “the following named negro slaves with their increase to wit Luke, Molly, Andrew, Doll, Antiny [alt: Anthony], Judy, Paul, Nancy [or Nancy], William, Flora, Frank, Prince, Jack, Flanders, Antoinette, Toney, March, Cain, old Paul, Charlotte, Edward, Rose, Josephine, Sue, Clarinda, Jennet, Jim, Die [alt: Dye] and little Nancy…”

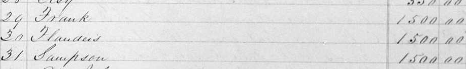

In 1864, when Charlton Hines, Lewis Hines’ brother, died, his estate inventory included Flora and her children: Flora, Daphne, Frank, Flanders, Sampson, Prince, Jack and Annette (possibly Antoinette?).[25] There were several Floras, but one was listed as “old Flora.” So it appears that they wound up in Charlton Hines’ hands.

![]()

What happened to John Pray Hines? He was the executor of Charlton Hines’ will and was to be his two youngest sons’ guardian. However, the month after Charlton Hines’ estate was inventoried and appraised, in June 1864, Captain John Pray Hines died at the Battle of Trevilian Station while commander of Company B, Hardwick Mounted Rifles, C.S.A. (Hines had been one of two delegates from Bryan County to the Georgia Secession Convention, where he voted in favor of secession.)

The surviving children of Lonnon and Chloe then became free when Sherman’s Army arrived in Liberty County in December 1865.

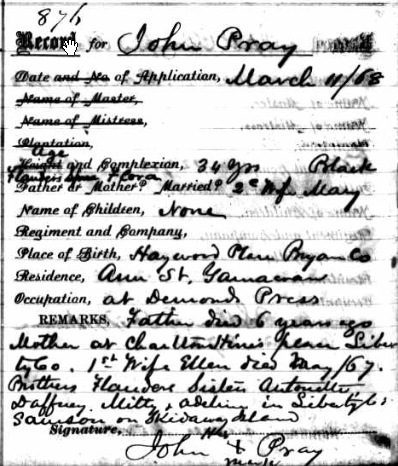

The above documents clearly lead to the conclusion that Lonnon and Chloe were Flanders Pray’s grandparents, and that Flanders and Flora were his parents, but a post-Civil War document makes it explicit. On March 11, 1868, John Pray, age 34, John Pray, age 34, married to Mary, listed his parents as Flanders and Flora in his Freedman’s Bank application in Savannah[26].

He said he had no children, and was born at Haywood Place in Bryan County, and was then living on Ann St in Yamacraw. He was working at Demond Press.

The account application’s remarks section said that his father had died 6 years previously and his mother was living at Charlton Hines’ place in Liberty County. His 1st wife, Ellen, had died in May 1867.

His brother, he said, was Flanders, and his sisters were Antonette, Daffney, Milty (probably Minty) and Adeline, all in Liberty County, and he had another brother, Samson, living on Skidaway Island. Their last names were not specified.

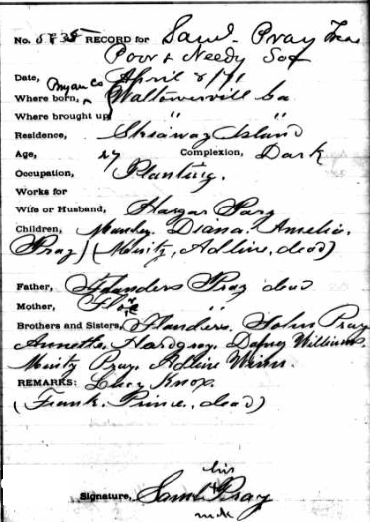

Another Freedman’s Bank record, this one from April 8, 1871, provides additional information[27]. Sam’l Pray was identified as the treasurer of the Poor Saints Society (also known as the Poor & Needy Society) of Skidaway Island. At that time, he was 27 years old and married to Hagar Pray. He identified his father as Flanders Pray, deceased, and his mother as Flora Pray. He identified his sisters as Annette Hargray, Dafney Williams, Minty Pray, Adline Winn, and Lucy Knox, and his brothers as Flanders Pray, John Pray. He said that his brothers Frank and Prince were dead. His children were identified as Manley, Diana, Amelia, with ?Kenity? and Adline deceased.

This Samuel Pray is presumably the brother who was identified as Sampson (or Samson) in earlier records.

This record confirms that Flanders (Sr) and Flora were the parents of Flanders (Jr), Antonette, Daffney, John (“Jack”), Sampson, Minty and Adeline. and that Flanders Sr was deceased and Flora was still living, at the Charlton Hines plantation, as of 1868. The records previously cited show that Lonnon and Chloe were the parents of Flanders Sr and that he had siblings named Peter, Bob, Charles and Clarinder (Clarinda).

Thus Flanders Pray’s family line can be traced as follows:

1808

–his grandparents Lonnon and Chloe and their children Peter, Bob, Charles, Flander (Flanders Pray’s father), and Clarinder purchased by John Pray at a Sheriff’s Sale in Bryan County (original owner James B. Maxwell)

1819

–his grandparents Lonnon and Cloe and their children Peter, Charles, Flanders, Clarinder and Sam bequeathed by John Pray to his goddaughter Mary Jane Pray Hines, wife of Lewis Hines of Bryan/Liberty County

1841

–In Lewis Hines’ estate inventory, Flanders Pray’s grandmother Chloe said to be at Bellmont Plantation; his father Flander, mother Flora, and her children Frank, Prince, Antonette, Jack, Flander, Daphne, and Sampson said to be at the Silk Hope Plantation in Bryan County

–Chloe and her son Flanders named in a lawsuit over Lewis Hines’ estate and said to be the lawful property of John Pray Hines

–Flora, Frank, Prince, Jack, Flanders, and Antoinette named in a lawsuit over Lewis Hines’ estate

1864

–in Charlton Hines’ estate inventory, Flora, Daphne, Frank, Flanders, Sampson, Prince, Jack and Annette (probably Antoinette) named

1868

–John Pray’s Freedman’s Bank account named his parents and Flanders and Flora and his siblings as Flanders, Antonette, Daffney, Minty, Adeline and Samson

1871

–Sam’l Pray’s Freedman’s Bank account named his parents as Flanders and Flora, and his siblings as Annette Hargray (probably Hargreaves), Dafney Williams, Minty Pray, Adline Winn, Lucy Knox, Flanders Pray, John Pray, and Frank and Prince (deceased)

-

“Georgia, Returns of Qualified Voters and Reconstruction Oath Books, 1867-1869,” Liberty County, Georgia, Precinct 2, Election District 2, entry for Flanders Pray, voter #115; database images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1857/images/32305_1220705227_0257-00041 : accessed 11 May 2024), image 71 of 100. ↑

-

Jennifer Carol Lund Smith, “’Twill take some time to study when I get over”: Varieties of African-American Education in Reconstruction Georgia, Ph.D. thesis at University of Georgia, 1997. Also, letter from William A. Golding to Col. J.R. Lewis in Atlanta, Georgia, Freedmen’s Bureau Records (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9TH-K95S-B : accessed 12 May 2024 via experimental full-text search). ↑

-

“Baconton Missionary Celebrates 150 Years,” Coastal Courier, May 27, 2029, online at https://coastalcourier.com/news/baconton-missionary-celebrates-150-years/. ↑

-

U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878, for Flanders -> Superintendent of Education, NARA series M799, Roll 28; indexed digital database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/62309/images/007675840_00149 : accessed 12 May 2024), image 149 of 154. ↑

-

Jennifer Carol Lund Smith, “’Twill take some time to study when I get over”: Varieties of African-American Education in Reconstruction Georgia, Ph.D. thesis at University of Georgia, 1997. ↑

-

“A Study in Courage: Liberty County’s African American Voters in 1868,” by Stacy Cole on the They Had Names website. See https://theyhadnames.net/2023/10/18/a-study-in-courage-liberty-countys-african-american-voters-in-1868/. ↑

-

“Supervisors of Elections: List of Appointments by Judge Erskine,” Savannah Morning News, October 28, 1874, page 3. ↑

-

Georgia State Gazetteer, Business and Planter’s Directory, Vol. II, 1881-82, A.E. Scholes & Co., Publishers, Offices: Augusta, Macon, Atlanta, Savannah, Columbus. Copied in 1976 by Joe Baggett from the originals at the Carnegie Library, Atlanta, Ga. ↑

-

Two of those were County Ordinary Joseph Ashmore and Court Clerk J. Sloeman Ashmore, both of whom had been officers in the C.S.A. 25th Infantry Regiment. ↑

-

The 1870 census did not list relationships. 1870 U.S. census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Subdivision 180, page 23, dwelling 225, family 225, enumerated in November,1870, by Robert Q. Baker, entry for Flanders Pray household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7163/images/4263491_00403 : accessed 11 May 2024). ↑

-

1880 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, District 15, enumeration district 67, page 66, dwelling 712, family 716, entry for Flanders Pray household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6742/images/4240148-00466 : accessed 11 May 2024). ↑

-

Based on a search of the Liberty County Superior Court deed record indexes found online at FamilySearch.org and on the property tax records found, which only show him paying tax on personal property from 1878-1885.. ↑

-

Flanders Pray put up this property as security as a bond for his neighbor, Abner Hargraves, in a domestic violence case. “Georgia Probate Records, 1743-1990” > Liberty County > “Estates 1775-1892 Goulding, Peter-Harris, Ann” image 840 of 1101; digitized folders, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9Q4-Z62X : 11 May 2024). ↑

-

Liberty County, Georgia, Deeds & Mortgages, 1885-1886, Book X, pages 200-1 ; digitized microfilm accessed through catalog, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-R9T8-D : accessed 11 May 2024), Family History Library microfilm 008564338, image 109 of 448; citing original records of Liberty County Superior Court, Georgia. ↑

-

Liberty County, Georgia, Deeds & Mortgages, 1885-1886, Book W, pages 454-5; digitized microfilm accessed through catalog, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-GJ3R: accessed 12 May 2024), Family History Library microfilm 008564337, image 460 of 525; citing original records of Liberty County Superior Court, Georgia. ↑

-

The 1900 census asked participants how long they had been married and how many children a woman had had. 1900 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Militia District 1458, enumeration district 87, sheet 3, line numbers 13-22; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7602/images/4120072_00081 : accessed 11 May 2024). ↑

-

1910 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Militia District 1458, enumeration district 121, sheet 4A, line numbers 18-23, family #61; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7884/images/31111_4327500-00847 : accessed 11 May 2024). ↑

-

Bryan County, Georgia, Deeds & Mortgages, v. A-D 1796-1829, Book C (1807-1815), page 49-50; digitized microfilm accessed through catalog, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4K-KSKG: 26 May 2024), image 289-90 of 600; microfilm #007899046, citing original records of Bryan County Superior Court. ↑

-

For a transcribed copy of John Pray’s 1819 will, see https://theyhadnames.net/2024/08/14/chatham-county-will-john-pray/. Three recorded copies of John Pray’s will were found: Chatham County, Georgia, Court of Ordinary, Probate Records, probate records for John Pray, folder 66; Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/705489:8635 : accessed 14 Aug 2024), “Georgia, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1742-1992” -> “Chatham” -> “Probate Records, Page-Putman, Folder 1-103,” images 1057-1071. Chatham County, Georgia, Court of Ordinary, Wills, Book F (1817-1827), Will of John Pray, pages 72-95; FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L93G-F9F2 : accessed 14 Aug 2024), Chatham County Wills v. E-F (1807-1827), Book E, images 291-302; from Family History Library Film #005759792 of original records at the Chatham County Courthouse, Savannah, Georgia. The third copy can be found at an be found in Pray et al. V. Belt in Baltimore County Court 1821 (https://www.google.com/books/edition/PRAY_et_al_v_BELT_et_al_26_U_S_670_1828/ZNbtS8BLfAMC : accessed 14 Aug 2024). Suit by George Gordon Belt trustee for Jas. P. Heath pro ami against John Pray’s executors.] ↑

-

“Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-GC4N?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 583 of 689 ↑

-

Loose Papers in folders by surname, Liberty County Court of Ordinary, 1841 estate papers for Lewis Hines; digitized images with typewritten indexes, FamilySearch.org (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8635/images/005764238_00645 : accessed 22 Aug 2023), “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990 -> Liberty -> Estate Records 1775-1892 Harris, Isaac-Hornby, Phillip, image 636 of 1188. ↑

-

Bryan County, Georgia, Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1830-1853, Book F (1840-46), page 133-4; digitized microfilm accessed through catalog, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4K-VSLD-L : 6 Sep 2024), image 317-8 of 682; microfilm #007899047, citing original records of Bryan County Superior Court. ↑

-

Bryan County, Georgia, Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1830-1853, Book F (1840-46), page 150-2; digitized microfilm accessed through catalog, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4K-VSLX-9 : 6 Sep 2024), image 327-8 of 682; microfilm #007899047, citing original records of Bryan County Superior Court. ↑

-

Loose Papers in folders by surname, Liberty County Court of Ordinary, 1841 estate papers for Lewis Hines; digitized images with typewritten indexes, FamilySearch.org (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8635/images/005764238_00647 : accessed 22 Aug 2023), “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990 -> Liberty -> Estate Records 1775-1892 Harris, Isaac-Hornby, Phillip, image 637 of 1188. For a transcription of the court case, see https://theyhadnames.net/2023/08/23/court-case-against-lewis-hines-estate-naming-numerous-enslaved-people-1841/ ↑

-

Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L93L-RJ96: 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills 1863-1942 vol C-D > image 43 of 430. For an abstract listing all the names in the inventory, see https://theyhadnames.net/2019/03/18/liberty-county-estate-inventory-charlton-hines/. ↑

-

U.S. Freedman’s Bank Records, March 11, 1868, for John Pray; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8755/images/GAM816_8-0135 : accessed 9/4/2024), “U.S., Freedman’s Bank Records, 1865-1874” -> “566522 – Registers of Signatures of Depositors, 1865-1874”-> “Roll 08: Savannah, Georgia; Jan 10, 1866-Dec 17, 1870,” image 135 of 689. ↑

-

.S. Freedman’s Bank Records, March 11, 1868, for John Pray; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8755/images/GAM816_8-0135 : accessed 9/4/2024), “U.S., Freedman’s Bank Records, 1865-1874” -> “566522 – Registers of Signatures of Depositors, 1865-1874”-> “Roll 09: Savannah, Georgia; Dec 17, 1870-Oct 22, 1872,” image 132 of 686. ↑