Jacob Dryer submitted a claim under the U.S. Southern Claims Commission in 1877, after being held in slavery most of his life by George W. Walthour. He became a prosperous farmer after the Civil War. (For the full transcription of his claim and research into his life after the War, click here.) Transcribed deed and probate records have allowed research into his life before the Civil War and his family lineage, tracing back into the 1790s.

Family Lineage of Jacob Dryer

Summary

Jacob Dryer and his wife Maria, formerly enslaved, lived in Liberty County all their lives. Jacob Dryer was a “very prosperous and thrifty man,”[1] who bought and sold land after the Civil War and lived into the early part of the 20th century. Maria survived him.

“He is said to have feared the slavery of debt as much as he did the old slavery. Ask anyone in his vicinity how Jacob Dryer is getting on and the reply is splendid.” ~U.S. Southern Claims Commission Special Agent R.B. Avery, 1878

Jacob Dryer’s parents were Jacob and Celia, whose other children as of 1830 were Maryland, Linda, Delia, Adam, and Chloe. Jacob was the youngest, born around 1832-1833. Jacob and his wife Maria named two of their daughters, Lindy and Delia, after his sisters.

Jacob Dryer’s possible grandparents were Lancaster and Affey, who also had a child named Lancaster. Jacob Dryer named his son Lancaster.

Jacob Dryer’s surname came from an early enslaver of his family, Nathan Dryer, who died in 1808 while owning Lancaster, Affey, and Jacob Sr. Lancaster and Affey had come into Dryer’s possession through his wife, Elizabeth Hext Dryer, who inherited them from her father, John Hext at his death in the mid-1790s. (John Hext had come to Liberty County from Charleston, South Carolina, where he was a member of a prominent family.)

Lancaster, Affey and Jacob Sr passed into the possession of William Ward when Eliza Hext Dryer married him after Nathan Dryer’s death. During this time, Jacob Jr married Celia. After William Ward’s death in 1830, Lancaster, Affey, Jacob Sr and his wife Celia, and infant Jacob (Dryer) were inherited by Ward’s widow, Sarah C. Ward. Jacob Sr and Jr were sold by Ward’s widow in 1837 to George W. Walthour, where they remained until the Civil War.

Evidence

Jacob Dryer testified in his 1877 petition to the U.S. Southern Claims Commission[2] that he had been held in slavery on George W. Walthour’s Westfield plantation in Liberty County. It appeared that he had been there since at least 1841, because Walthour’s son Russell, who was born in 1841, testified that he had known Dryer all his life.[3]

Which Jacob?

In George W. Walthour’s 1859 estate inventory, four enslaved men named Jacob were listed[4].

–Jacob, valued at $250, 60 years old, on Richland Plantation [imputed birth year 1799]

–Little Jacob, valued at $900, 33 years old, Richland Plantation [imputed birth year 1826]

–Jacob, valued at $850, 45 years old, Westfield Plantation [imputed birth year 1814]

–Jacob, valued $1000, 28 years old, Westfield Plantation [imputed birth year 1831]

Jacob Dryer testified in 1877 that he was 40 years old at that time, which would put his birth year at around 1837. Census records from 1870-1900 put his birth year between 1820-1830[5]. When registering to vote in August 1867, he stated that he had lived in the precinct, county, and state for 40 years, indicating a birth year of around 1827[6]. No other Jacob Dryer was registered to vote in Liberty County that year.

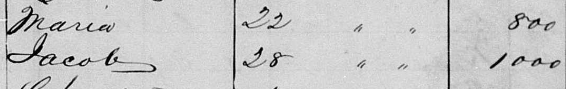

The wild variation in birth years is not particularly unusual for this time period and these records, but still leaves only 45-year-old Little Jacob on Richland plantation and 28-year-old Jacob on Westfield plantation as possibilities for Jacob Dryer. Jacob Dryer had said he was on Westfield plantation, leaving only one possibility. Further reinforcing this is the fact that Jacob Dryer had married Maria around 1860[7], and a 22-year-old Maria was listed next to Jacob in this inventory.

Jacob and Maria shown at Westfield Plantation of George W. Walthour, 1859

Jacob Dryer testified in his Southern Claims Commission petition that his father had given him a colt, further evidence that they lived on the same plantation and knew each other.

Why Dryer?

Why did Jacob Dryer adopt the surname Dryer at Emancipation? Why not Walthour?

Let’s go back farther in time and examine the possibility that Jacob had that surname because of an earlier enslaver of his family.

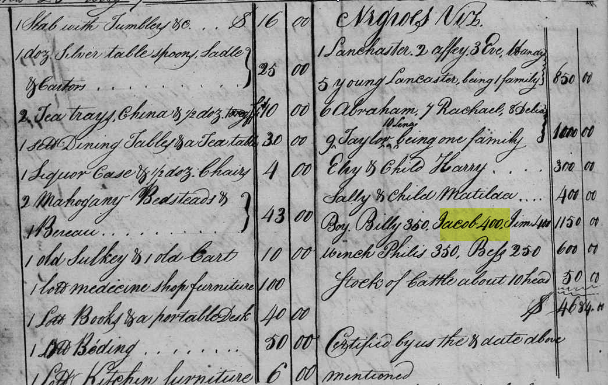

In March 1808, an estate inventory was performed for Dr. Nathan Dryer of Liberty County[8]. Dryer’s widow, Mrs. Eliza Dryer, formerly Elizabeth Hext, was the estate administrator. Five enslaved people were listed separately (i.e., not as part of a family) in the inventory: Billy (a boy), Jacob, Jim, Philis, and Bess. The estate inventory also listed four families of enslaved people.

| Lanchaster | Abraham | Elsy | Sally |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affey | Rachael | Harry (a child) | Matilda (a child) |

| Eve | Delia | ||

| Handy | Taylor | ||

| Lancaster | Lena |

1808 Nathan Dryer estate inventory

1808 is too early for the Jacob in this estate inventory to be Jacob Dryer; however, remember that there were two older men named Jacob in the George W. Walthour estate inventory. The Jacob who was 60 years old could have been this Jacob. Could it have been Jacob Dryer’s father or other relative named in the Nathan Dryer estate inventory? And perhaps this was why Jacob Dryer took that surname?

1808: Jacob (Sr) in Nathan Dryer’s estate inventory. Also Lanchaster and Affey and their child Lancaster.

John Hext

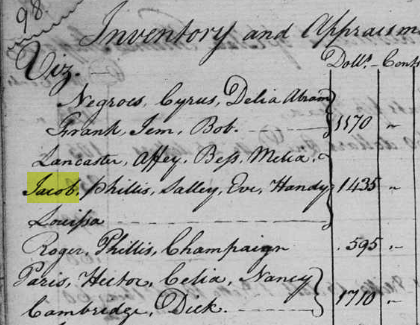

Let’s step further back into time. Dr. Nathan Dryer had married Elizabeth Hext on September 1, 1801.[9] In the mid-to-late 1790s, her father, John Hext, had died. His Liberty County estate inventory[10] listed in enslaved people in groups, which were likely family groupings:

–Cyrus, Delia, Abram, Frank, Jem, Bob

–Lancaster, Affey, Bess, Melia, Jacob, Phillis, Salley [alt: Sallie], Eve, Handy, Louissa [alt: Louisa]

–Roger, Phillis [alt: Phyllis], Champaign

–Paris, Hector, Celia, Nancy, Cambridge, Dick

–Isaac Bob

–Quash, Rinah, Joe, Jem, Patty, Elsey, June, Peggey [alt: Peggy], Bess, Hannah

–George, Jack

–George, Prissey, Primus, Lindy, Abram, Tena, Delia, Lucy, Caroline

–Nancey [alt: Nancy], Betty, Sarah, Sam, Myra, Louissa [alt: Louisa], Eward [Edward], Polly, Celia

–Jenny, Cudjo, Hannah, Nelley, Wallace, Shadwell

Estate Inventory, John Hext, mid-to-late 1790s

Note that Lancaster, Affey, Bess, Melia, Jacob, Phillis, Salley, Eve, Handy, and Louissa are grouped together in Hext’s estate inventory. In Dryer’s 1808 inventory, Lancaster, Affey, Eve, Handy, and young Lancaster were explicitly named as a family, although Jacob was not included in the group that time. The Jacob who was 60 years old in 1859 would not have been born at the time of Hext’s estate inventory; however, it appears very likely that there was a family connection with Lancaster because in 1866, Jacob Dryer named his son Lancaster[11].

Hext’s 1787 will[12], made in Charleston, South Carolina, named his daughters as Eliza and Maria Hext. Hext apparently had debts when he died, because in 1798 the Liberty County sheriff seized George, Cudjo, Peggy, Celia, Lindy, Carolina, Prissy, Lucy, Lydia and Polley from the estate administrators and sold them at auction to Samuel Proctor Bayley[13], who had married Maria Hext earlier that year. At the same time, George, Nancy, Sarah, Myra, Louisa, Edward, Romeo, Delia, and Shadwell were also seized and sold, this time to Elizabeth Farrar[14].

Although records were not found to show which enslaved people Elizabeth Hext Dryer had inherited, it is evident from the names in her father’s estate inventory and names in her husband’s estate inventory that many of the people named were the same.

Mid 1790s: Lancaster, Affey, Jacob in John Hext’s estate inventory

After Nathan Dryer’s death

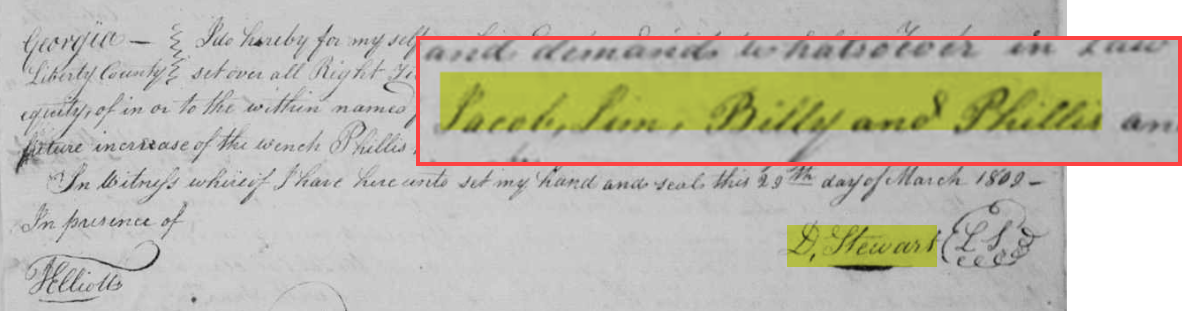

Nathan Dryer appeared to have also had some debts prior to his death, as several enslaved people in his estate were seized by court order and sold at the courthouse steps in Hinesville to pay his debts. On March 28, 1809, Jacob, Jim, Billy, and Phillis were sold in this way to General Daniel Stewart[15]. The next day, Stewart transferred his rights to them back to Elizabeth Dryer.

Jacob seized and sold to pay Nathan Dryer’s debts, 1808

In April 1809, Elsy and Harry were seized and sold at auction to James E. Morris[16]. On October 2, two enslaved people not named in the estate inventory, Amelia and June, were seized as a result of lawsuits against Dryer and sold at a Sheriff’s sale. They were purchased by Stephen S. Wing, who was one of the parties bringing the lawsuits. He then sold them back to Mrs. Dryer[17]. The court record noted that they had been the property of her late husband Nathan Dryer and that she was the natural guardian of her children named Edmund and Elizabeth.

William Ward

No records were found to show which enslaved people from Nathan Dryer’s estate were inherited by Eliza Dryer and her children Edmund and Elizabeth, but on February 4, 1810, Eliza Hext Dryer married William Ward[18], and on February 5, they entered into a marriage contract that stipulated that any property she brought into the marriage was to be put into trust for her[19]. Included in this trust were Jacob, Jim, Billy and Phillis, whom she appears to have inherited from Dr. Dryer. It is likely that the other people were put into trust for her children.

William Ward was appointed guardian to Edmund and Elizabeth Dryer on January 28, 1811, and thus probably controlled the trust. This may actually have been due to Elizabeth’s death, because William Ward entered into a marriage contract with Miss Euphemia McIver on February 13, 1812[20]. The contract created a trust, and placed in the trust were the enslaved people and land Euphemia was bringing into the marriage.

1810: Jacob in Eliza Hext Dryer’s marriage contract with William Ward

Elizabeth Hext Dryer Ward’s 1823 estate inventory

It is likely that the trust Ward had created for Elizabeth and probably for her children was maintained until her children, Elizabeth and Edmund, were of age. It was the usual practice to re-inventory the estate when an heir became of age and then divide the estate among the eligible heirs. This was done with Elizabeth’s estate on March 31, 1823, when the enslaved people in the estate were valued and divided among William Ward, Edmund Dryer and Elizabeth (now) Broadmax[21].

Because Lancaster (now spelled Lanchester) and Affy were named in Elizabeth’s estate but not in the marriage contract, it appears likely that they were in trust for her children.

| Enslaved | Value | Description | Lot # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jim | 250 | 1 | |

| Jacob | 450 | 1 | |

| Billy | 450 | 2 | |

| Philis | 400 | [alt: Phyllis] | 3 |

| Lanchester | 400 | 3 | |

| Stephen | 250 | 2 | |

| Affy | 225 | [alt: Affee] | 2 |

| Eliza | 150 | 1 | |

| Charles | 100 | 3 | |

| June | 450 | “This negro left to Edmund Dryer & Elizabeth his sister by Mr. Richard B. Law, as per bill of sale” |

Unfortunately, although the lots were numbered in the division, the estate inventory did not say who received which lot. Lot numbers were normally written on a piece of paper and put into a hat to be drawn at random by the heirs.

Eliza Hext Dryer Ward’s 1823 estate inventory

1823: Lancaster, Affey, and Jacob in Eliza Ward’s estate inventory

William Ward’s 1830 Death

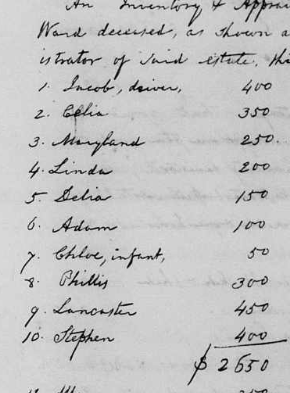

William Ward, who was astonishingly unlucky in marriage, having married in rapid succession Elizabeth Hext (1810), Euphemia McIver (1812), Sarah Ann McIntosh (1813), and Sarah C. Maxwell (1826), died in 1830[22]. His estate was inventoried shortly after his death, on July 24, 1830, as was customary[23]. The first seven people listed in the inventory were listed in order by valuation, normally indicating a family:

Jacob ($400 and a driver)

Celia ($350)

Maryland ($250)

Linda ($200)

Delia ($150)

Adam ($100)

Chloe ($50, “infant”).

1830 William Ward estate inventory

Also in the inventory was another individual named Jacob (valued at $250 so either young or old), as well as Billy ($400), Billy ($400), Jim ($200), Phillis ($300), Lancaster ($450), Affy ($350). Only Bess of the individuals inherited by Eliza Dryer from Nathan Dryer appears to be missing.

It can be seen that Jacob Sr appears to have married Celia, and that Maryland, Linda, Delia, Adam, and Chloe were their children. Remember that there was two Celias in John Hext’s estate inventory, one in the family grouping of Paris, Hector, Celia, Nancy, Cambridge and Dick, and the other in the family grouping of Old Nancey, Betty, Sarah, Sam, Myra, Louissa, Edward, Polly, and Celia. It is likely that Jacob’s wife Celia was one of these Celias, and thus her ancestry could also potentially be traced back further.

Note also that there were individuals named Lindy and Delia in Nathan Dryer’s estate. (And in 1804, Nathan Dryer had gifted a boy named Adam to his son John Edmund Hext Dryer.[24]) These are not uncommon names; however, it appears evident that they were important names within Jacob Dryer’s family, because he named two of his daughters Lindy and Delia.

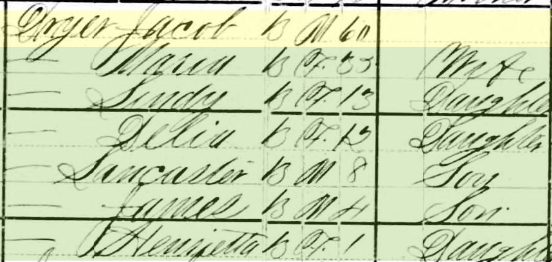

1880 census record for the Jacob and Maria Dryer household

Naming patterns were very important in both White and Black families of the time. It was common to name children after grandparents, and also after aunts and uncles.

1830: Lancaster, Affey, and Jacob in William Ward’s estate inventory. Jacob now married to Celia

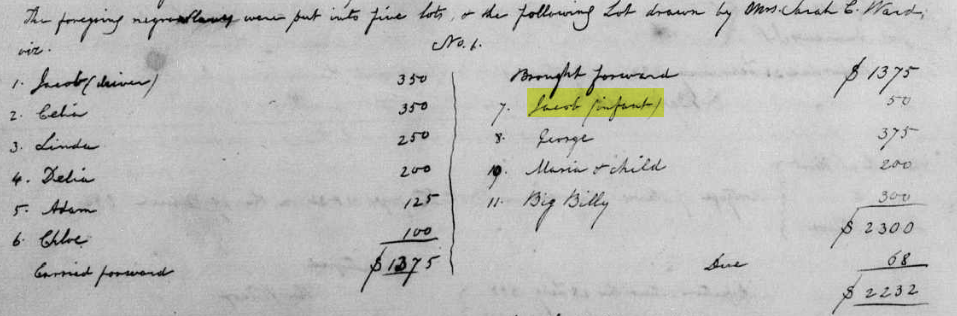

William Ward’s Estate Divided in 1833 – Infant Jacob

William Ward’s estate was appraised and divided on February 13, 1833, because his widow, Sarah C. Ward had petitioned the court for “a division of the negro slaves belonging to the estate of William Ward, her deceased husband, in behalf of herself.”[25] Everyone was valued and divided into five groups, and Sarah Ward drew lot number 1, comprised of:

Jacob, $350, “driver”

Celia, $350

Linda $250

Delia $200

Adam $125

Chloe $100

Jacob $50, “infant”

William Ward estate inventory, February 1833

It appears obvious that Jacob and Celia were the parents of the others, based on the descending order of value of the people listed after their names. Jacob had been born since the previous inventory, so was evidently born in late 1832 or early 1833.

William Ward’s estate was inventoried and divided again on March 7, 1833[26], and the remaining enslaved people named in the inventory were divided into four lots and drawn by William Maxwell, guardian of John C. and Louisa V. Ward, and John S. Maxwell, guardian for William Wallace Ward and Georgia Elizabeth Ward[27].

It appears that Celia and Adam may have passed away by this time as they were not included.

1833: Lancaster, Affey, Jacob, Celia, and infant Jacob in William Ward’s estate inventory & division

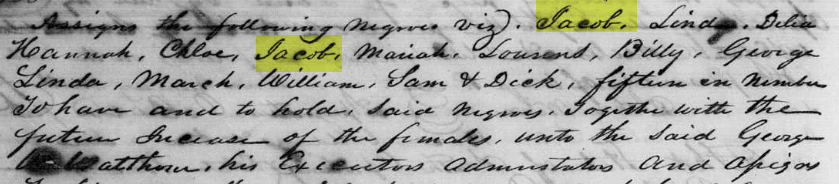

Sold to George W. Walthour

In February, 1837, Sarah C. Ward sold to George W. Walthour for $9000 “the following negroes viz. Jacob, Lindy, Delia, Hannah, Chloe, Jacob, Mariah, Lourens [?, maybe Laurens or Laurence, Lawrence?], Billy, George, Linda, March, William, Sam & Dick, fifteen in number…”[28]

Thus Jacob (Sr) and children Linda, Delia, Hannah, Chloe, and Jacob, came to the George W. Walthour plantation.

1837 sale by Sarah C. Ward to George Walthour

By July, 1847, Sarah C. Ward, guardian of Wallace and Georgia Ward, had moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where she applied to the Liberty County Superior Court for permission to have 29 more enslaved people sold at auction at the Hinesville courthouse on April 6. They were also sold to George W. Walthour.[29] This group also did not include Celia or Adam, supporting the idea that they may have died prior to this. (The 29 people were Nancy, Joe, Phoebe, Jack, Cato, Betsy, Paul, Flora, Nancy, Ginny, Dianna, Jacob, Patty, Abby, Forty More, Sarah, ? Nan ?, Mary, Margaret, Sam, Sambo, Clarissa, William, Rose, Toney, John, Peggy, Cristena [alt: Christina] and Harriet.)

1837: Jacob (Jr), Jacob (Sr) sold to George Walthour by William Ward’s widow

George Walthour’s 1859 Death

As has been seen, when George W. Walthour died in 1859, his estate included Jacob (Sr), now 60 years old and on the Richland plantation, and Jacob, now listed as 28 years old, on the Westfield plantation. Jacob Dryer married Maria around 1860, and in fact, 28-year-old Jacob on the Westfield plantation is listed next to a Maria, further reinforcing the idea that he was Jacob Dryer.

When Walthour died, he still had four minor children[30], so his estate would have been held together until they came of age. No further records were found. The Civil War is likely to have intervened, and so Jacob and Maria Dryer passed from slavery into freedom.

- “U.S. Southern Claims Commission Allowed Claims, 1871-1880,” Liberty County, Georgia, case file of Jacob Dryer, #20685; indexed database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1217/images/RHUSA1871A_118421__0039-01447 : accessed 16 May 2023), image 101 of 147; citing National Archives Microfilm Publication M1658, Settled Case Files for Claims Approved by the Southern Claims Commission, 1871-1880; citing Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, Record Group 217; National Archives, Washington, D.C. For complete transcription of case file and research on the claimant, see: https://theyhadnames.net/2020/05/16/jacob-dryer-southern-claims-commission/. ↑

- Ibid (Southern Claims Commission). ↑

- Indicating that Jacob had been on the plantation since at least the time Russell Walthour was old enough to recognize him. ↑

- ”Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-993T-XTF2?cc=1999178&wc=9SB7-6T5%3A267679901%2C268014801 : 16 May 2023), Liberty > Miscellaneous probate records 1850-1863 vol C and L > image 231 of 703. ↑

- The 1870 and 1880 federal census records stated he was born 1820 or 1821. The 1900 census record stated he was born in 1830. Other identifying data remained the same. Such a wide swing was not unusual. ↑

- “Georgia, Returns of Qualified Voters and Reconstruction Oath Books, 1867-1869,” Liberty County, Georgia, Precinct 2, Election District 2, entry for Jacob Drier [Garrison crossed out and Drier written over it], voter #54; database images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1857/images/32305_1220705227_0257-00039: accessed 16 May 2023), image 69 of 100. ↑

- 1900 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Militia District 15, Riceboro town, enumeration district 80, sheet 13, line numbers 67-70, Jacob and Mariah Dryer household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7602/images/4120071_00570 : accessed 16 May 2023). ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-893L-PR5?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 16 May 2023), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 291 of 689. ↑

- Ancestry.com, Georgia Marriages, 1699-1944, Nathan Dryer to Elizabeth Hext, September 1, 1801, no image available (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/89354:7839 : accessed 16 May 2023). ↑

- ”Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-P931?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 16 May 2023), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 221 of 689. ↑

- 1870 U.S. census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Subdivision 180, page 9, dwelling 92, family 92, enumerated on November 16, 1870, by Robert Q. Baker, entry for Jacob and Maria Dryer household; digital image, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7163/images/4263491_00389 : accessed 16 May 2023); citing NARA microfilm publication M593_162, page 192A. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-P9L5?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 16 May 2023), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 59 of 689; county probate courthouses, Georgia. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. C-D 1793-1801,” Record Book D, 1798-1801, p. 86. Image #630 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-5BZ7?i=629). ↑

- Based on other records, Elizabeth Farrar appears to have been related to the Hext family. It is possible that she was Hext’s wife and that she had remarried shortly after his death. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1801-1816,” Record Book F (1804-1809), p. 226. Image #280 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QL-J982-V?i=279) ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1801-1816,” Record Book G (1809-1816), p. 65. Image #332 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QL-J9ZY-5?cat=292358). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1801-1816,” Record Book G (1809-1816), p. 37. Image #318 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QL-J9DW-B?i=317&cat=292358). ↑

- Liberty County, Georgia, Court of Ordinary Marriages White & Colored, Book A, 1819-1896, indexed by men’s names, entry for William Ward to Mrs. Eliza Dryer, February 4, 1810, marriage performed by Revd. Charles O. Scriven, Liberty County, Georgia; database images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/4766/images/40660_307901-00152 : accessed 16 May 2023); citing County Marriage Records, 1828-1978, Georgia Archives, Morrow, Georgia. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1801-1816,” Record Book G (1809-1816), p. 103-4. Image #352-3 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QL-J9ZR-9?i=351&cat=292358). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1801-1816,” Record Book G (1809-1816), p. 187-91. Image #398-400 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QL-J9DX-1?i=397&cat=292358). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, p. 35. Image #319 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSRC-Y?i=319&cat=292358). ↑

- William Ward’s death must have occurred between a deed of gift to his daughter Louisa dated December 3, 1829 and his July 1830 estate inventory. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-PV?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 16 May 2023), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 485 of 689. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1801-1816,” Record Book F (1804-1809), p. 30. Image #179 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QL-J96N-Y?i=178). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, p. 69-70. Image #71-2 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T9VR-L?i=70&cat=292358). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, p. 73-4. Image #74-5 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T9K8-C?i=73&cat=292358) ↑

- William Ward’s children by other wives. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, 1831-1838, pp. 364-5. Image #233-4 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T9K8-K?i=232&cat=292358). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. M-N 1842-1854,” Record Book M, pp. 644-5. Image #373 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-5ZM5?i=372&cat=292358) ↑

- ”Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-993T-XTZT?cc=1999178&wc=9SB7-6T5%3A267679901%2C268014801 : 16 May 2023), Liberty > Miscellaneous probate records 1850-1863 vol C and L > image 235 of 703. ↑