Research performed by Stacy Cole (updated as of 2/5/2023)

On July 4, 1889, when Georgia’s new Capitol Building was dedicated, there was just one African American member of the Georgia General Assembly. He was Samuel A. McIver, representing Liberty County.

How did he get there?

Early Life

Samuel A. McIver was born into slavery in Liberty County, around November 1816.[1] It appears likely that his early enslavers were Major John Stevens and later Stevens’ son Dr. James D. Stevens, descendants of one of the first European settlers of the Midway area.[2]

In 1847, an inventory was performed of the estate of James D. Stevens showing that he owned an enslaved man named Sam who held the position of “driver,” a supervisory position of trust on a plantation.[3] Stevens’ children were all minors; as will be seen later, his widow held the estate together until 1859 so it appears likely that Sam continued in that location until then.

James D. Stevens was the son of John Stevens (1777-1832), who was likely Sam’s previous enslaver. John Stevens was collector of the port of Savannah, director of the Bank of the State of Georgia, and a member of the state legislature.[4] He died in Savannah in 1832, and his widow returned to Liberty County to their plantation Palmyra,[5] where she died in 1859.[6]

Meanwhile, Margaret McIver and two children, Sam Jr. and Matilda, were listed in “free persons of color” registers in Liberty County from 1852-1859.[7] Her residence was listed as the estate of J.D. Stevens and her sponsor (required to be a white man) was Joseph C. Wilkins, a relative of Stevens through marriage. Matilda later testified that her mother Margaret was born free.[8]

As will be seen later, Margaret and Sam McIver left Liberty County for Chatham County in 1859, which explains why she was not listed in the Liberty County register after that year.

The enslaved man Sam who belonged to Dr. J.D. Stevens was admitted into membership in the Midway Congregational Church on August 16, 1846.[9] Margaret, listed as a free woman, was readmitted to the same church on the same day.[10] She had previously been excommunicated for adultery on February 27, 1841, and had applied to readmittance in 1845.[11] At that time, the Church noted that she was “entirely released from her former husband Isaac.”

It therefore seems likely that Margaret and Sam had been together as a couple since around 1841.The Midway Congregational Church has had both White and Black members since at least 1756, with all members going through the same admittance process.[12]

In 1859, Dr. James D. Stevens’ widow, Jane M. Stevens,[13] petitioned the Liberty County Superior Court, sitting in equity, to sell land and enslaved people from his estate, saying that although she had paid most of the debts, his 956-acre Oakland plantation was too small for the “number of hands.”[14] She said in her petition that she had purchased a 3000-acre plantation from Valentine Grest called the Bidiford Plantation, formerly owned by Joseph Maxwell, but poor crops, the low prices of Sea Island cotton, “the many casualties & expenses attending the management of negroes,” and the great expense of her children’s education and support had motivated her to sell Oakland and 28 named enslaved people.

Although Sam was not listed among this number, it is likely that she sold him privately, since in November 1859, the Midway Congregational Church granted letters of dismission to “Sam servant of Mr. Green of Savannah, for Margaret a free woman & Matilda a free woman” as “they desire to unite with the Independent Ch[urch] of Savannah.”[15]

Savannah and the Civil War

Charles Green, the English cotton merchant who later became President of the Savannah Bank and Trust Company and owner of the historic home now known as the Green-Meldrim House in Savannah, had purchased Sam as his personal driver.[16]

Samuel McIver testified in 1872 before a U.S. Southern Claims Commission officer about his time in Savannah.[17] He said that he and Margaret had lived in Savannah until the end of the Civil War, and while there, he was allowed by Green to hire out his time. He paid Green $12 a month and was able to make as much as $15 a day through driving a wagon. He said he had managed to buy two horses, a wagon and harness, two cows, and some hens and hogs.[18]

During the Civil War, McIver said, he was taken off his wagon in the street, and forced to help build fortifications for the Confederate Army. His horse and wagon made its way safely to his home, and he deserted after three days and never went back.[19] He said that Green was an Englishman and was “in Europe” at the time[20]; McIver appealed to his agent for protection from the Army but said he was ignored.

As Sherman’s army approached Savannah in December 1864, McIver was witness to one of the iconic events of the Civil War. In his own words[21]:

“I left Savannah & went out on the road the very morning I was captured. I went out on the road on business for myself expecting to return according to an engagement, and not expecting to meet the federal army. I fell into their hands & was captured. I was not held as a prisoner but went immediately into Col. Oliver’s service as a guide. I did it willingly & would do so again tomorrow if need be….after I was captured by Sherman’s Army I piloted the General [probably General Belknap] to Fort McAlister. I was there & witnessed the surrender of the Fort to Col. John Oliver of the Federal Army of the 3d division of the 14 corps… I was in the Federal lines & serving them as guide from the 8[th] of December, during the operations around Savannah till Dec 24th when I returned to my home in the City….when the Army came into Savannah I lived on Hall St. in North West part of the city. I kept my own house. Mr. Geo. Gardner & family lived next door to me. The army was encamped within about 30 yrds from my house. The headquarters of Genl. Belknap was about 60 or so yards from my house.”

McIver testified that when Sherman’s Army entered Savannah, they took most of his possessions, including the horses, the wagon, and the cows.[22] He sued the U.S. government for compensation via the U.S. Southern Claims Commission. Although a Southern Claims Commission investigator later cast doubt on his ownership of the property,[23] McIver was awarded $300 by the Southern Claims Commission.[24] Charles Green wrote a letter on his behalf in 1877, attesting that he did allow him to work for himself. He said, “I do know he was considered ‘well to do’ and from his more than average intelligence and industry I should think property to the extent [of] eight hundred to a thousand dollars a reasonable accumulation for his ability and opportunities.”[25]

According to McIver’s testimony before the Commission, his son S.A. McIver Jr, born a free man because his mother was free, had been pressed into service for the Confederate Army; McIver had opposed his going, but was unable to stop it. His daughter, Matilda Roberts, also testified for his SCC claim, stating that she was free born, lived in Savannah, and hired out as a washerwoman in addition to keeping house for her husband.[26]

In 1861, both Margaret (listed as age 50) and Matilda McIver (age 20) had been listed in the Savannah register for free persons of color, both as nurses.[27] Their white “guardian” was Charles Colcock Jones, Jr, then the Mayor of Savannah and also the son of Charles Colcock Jones Sr, a prominent Liberty County pastor and planter and a neighbor of Dr. James D. Stevens.

Back in Liberty County

After the end of the War, now in his late 40’s, McIver returned to Liberty County, where he rejoined the Midway Congregational Church. The Church was in disarray following the War, with many of the white members having moved to “offshoot” churches.[28] It attempted to keep going with the remaining White members and Black members, but in August 1867, McIver and another elder of the community, Tony Goulding, were deputized to tell the Church leadership that the African American members wanted to form a separate church and that they wanted to use the Midway Church building.[29] The structure, which dates to 1792, still stands today.

McIver’s early activism within his community is evidenced by his attendance at the Georgia Educational Convention, held in Macon, Georgia, on May 1-2, 1867. He and W.A. Goulding were the delegates from Liberty County.[30]

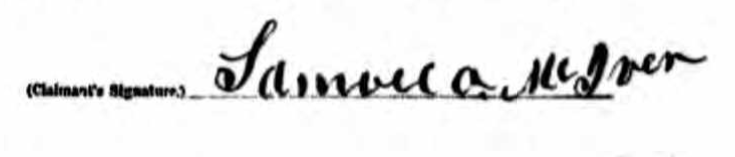

Despite the restrictions placed on enslaved people’s learning to read and write, McIver was literate, with beautiful penmanship, as evidenced by his signature on his 1871 Southern Claims Commission petition:

McIver took up farming in an area between Midway Church and Shavetown, with his wife and daughter. By 1880, he was renting 18 improved acres, and had an estimated farm production of $175, as much as some of his white neighbors.[31] By 1884, he owned a horse, mule, and 11 head of cattle that he ranged in Arcadia, Liberty County.[32] Margaret McIver appears to have died before 1889.[33] Her daughter, Matilda Proctor (who married Seaborn Proctor[34]), had died in 1876 and had been buried in Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah.[35] Matilda’s daughter Margaret Proctor was living with her grandparents in 1880.[36]

In the Georgia Assembly

Samuel A. McIver was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives in 1888. His election was bitterly contested, as his opponent, Newton J. Norman, charged that there had been illegal voting in the Riceboro precinct, where no white election managers had turned up on election day. Rev. Floyd Snelson and two others had sworn themselves in, opened the polls, and proceeded to administer the election, which went overwhelmingly in favor of McIver. Norman charged that the other two men were not freeholders and thus not qualified to administer the election and that many voters had not met the qualification requirements. McIver and Norman took the case to the Georgia General Assembly on November 24, 1888, where Committee on Privileges and Elections considered the charges point by point and decided in favor of McIver.[37]

McIver was considered “the most influential black leader in the [Liberty County] community” next to the Reverend Floyd Snelson; however, he was also said to be closely associated with the “conservative white power structure.”[38] While in the state legislature, he introduced a bill in the House proposing that a state university be established for the education of Georgia’s African Americans. It was to include a central college, four branches, and a school of technology, and the number of branch colleges was to be increased whenever the number of branch colleges reserved for white students was increased.[39] He also introduced a bill titled “A bill to establish an Industrial College for the colored girls of Georgia,” and was assigned to the insane asylum committee.[40]

By 1889, now elderly and the only remaining African American representative in the Georgia legislature, Representative McIver was referred to mockingly by the Georgia newspapers. Because of the tone and obvious racism of these articles, it is difficult to discern what parts of these stories are true. In one article, Representative McIver allegedly said he told visiting New York officials of his support for the South, including that he “served for Col. Jones of Augusta before the war, and when the southern troops marched to the field I went with them; I went with Col. Dick Aiken, and was with him at Fort Pulaski. Clear to the end of the war I fought for my people and was captured by Sherman in Georgia.”[41] This clearly contradicts his U.S. SCC testimony, which was much closer to the time in question, contains elements of this story, and was sworn testimony.

Final Chapter

McIver served one term (1888-1889) in the Georgia legislature. In the 1900 census, McIver was an 83-year-old farmer, a widower who had been married for 45 years and (according to the enumerator) with only one child living. He was not found in records after 1900, so presumably died before the 1910 census. In his household were his granddaughter Margaret J. Roberts, her husband Joseph W. Roberts,[42] and their children Celia (8), Josephine (6) and Willie (4) Roberts.[43]

Endnotes:

- The 1900 U.S. federal census gave the most specific date for McIver’s birth: November 1816. The 1870 and 1880 census records gave his age, which put his approximate birth year as 1816-1817. In his November 21st, 1872, testimony before a U.S. Southern Claims Commission official, McIver himself gave his age as 55. When McIver registered to vote in Liberty County, Georgia, in 1867, he swore that he had lived in the precinct, county and state for 49 years, indicating that he had been born in Liberty County; many other individuals who registered to vote in Liberty County were listed with varying numbers in the three columns, indicating that Liberty County officials were not just randomly filling out the form with the same number across the line.1870 U.S. census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Subdivision 181, page 39 (handwritten), dwelling 372, family 372, enumerated on November 22, 1870, by W.S. Norman, entry for Samuel and Margaret McIver household; digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7163/images/4263491_00474 : accessed 2/4/2023); citing NARA microfilm publication M593_162, page 234A.

1880 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, District 15, enumeration district 66, page 12 (handwritten), dwelling 122, family 124, entry for Samuel A. and Margaret McIver household; digital database, Ancestry https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6742/images/4240148-00368: accessed 2/4/2023), citing NARA microfilm publication T9, roll 155, page 6D.

1900 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Militia District 1476, enumeration district 88, sheet 1, line number 1; digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7602/images/4120072_00095: accessed 2/4/2023), citing Family History Library microfilm 1240209. .

- “Georgia, Returns of Qualified Voters and Reconstruction Oath Books, 1867-1869,” Liberty County, Georgia, Precinct 1, Election District 2, entry for Saml A. McIver, voter468; digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1857/images/32305_1220705227_0257-00027: accessed 2/4/2023), image 57 of 100; citing Georgia, Office of the Governor, Reconstruction registration oath books, 1867, Georgia State Archives, Morrow, Georgia.

“U.S. Southern Claims Commission, Allowed Claims, 1871-1880,” Chatham County, Georgia, case file of Samuel A. McIver, case #6609; indexed digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1217/images/RHUSA1871A_118415__0023-00888 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 12 of 257. ↑

- For further information on early Liberty County history, and the role of the Stevens family as early settlers, see: James Stacy, History and Published Records of the Midway Congregational Church, Liberty County, Georgia (Spartanburg, South Carolina: The Reprint Company, 2002). ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-GHVS?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 654 of 689. ↑

- Robert Manson Myers, The Children of Pride (Clinton, Massachusetts : The Colonial Press, Inc., 1792), page 1687. ↑

- The land on which Palmyra stood is currently owned by Meredith B. Devendorf, a direct descendant of the Stevens family. ↑

- Robert Manson Myers, The Children of Pride (Clinton, Massachusetts : The Colonial Press, Inc., 1792), page 1687. ↑

- These “free persons of color” registers for Liberty County were only found for the time period 1852-1864, although registration requirements had been on the books since 1819. See transcript of this “free persons of color” register at https://theyhadnames.net/2019/04/05/free-persons-of-color-1852-1864/, based on “Free persons of color 1852-1864,” Liberty County Superior Court, Liberty County, Georgia; unindexed digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C34P-NWJ6-B : accessed 2/4/2023), images 251-257 of 330. ↑

- “U.S. Southern Claims Commission, Allowed Claims, 1871-1880,” Chatham County, Georgia, case file of Samuel A. McIver, case #6609; indexed digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1217/images/RHUSA1871A_118415__0023-00888 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 25 of 257. ↑

- “Midway Congregational Church Records,” quarterly session records, Liberty County, Georgia, 1762-1867, Sam belonging to Dr. J.D. Stevens admitted to membership, August 16, 1846, page 589; digital images, FamilySearch ((http://familysearch.org : accessed 5/14/2020); image 585 of 899. Note: Records abstracted at https://theyhadnames.net/midway-church-records/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- “Midway Congregational Church Records,” quarterly session records, Liberty County, Georgia, 1762-1867, Sam belonging to Dr. J.D. Stevens admitted to membership, August 16, 1846, page 589; digital images, FamilySearch ((http://familysearch.org : accessed 5/14/2020); images 455-6, 478, 481, 484 of 899. Note: Records abstracted at https://theyhadnames.net/midway-church-records/. ↑

- Based on the author’s research. See https://theyhadnames.net/midway-church-records/. ↑

- In 1889, a newspaper article mentioned that Representative McIver had gone to visit “his Old Marster” in Rome, presumably Georgia. Mrs. Jane M. Stevens, widow of Dr. James D. Stevens, was living in Rome, Georgia, with her daughter at that time. August Chronicle, November 3, 1889, page 3. ↑

- Superior Court proceedings, Vol. 6, 1855-1864, Liberty County, Georgia, pp 339-40; database with images, “Liberty County Superior Court Proceedings, Vols 6-7 1855-1885,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3H3-7B1 : accessed 4 Sep 2022), Family History Library Film 175262 (DGS 008628086), images 197-8 of 702. ↑

- “Midway Congregational Church Records,” quarterly session records, Liberty County, Georgia, 1762-1867, Sam belonging Mr. Green of Savannah and Margaret and Matilda, both free women, granted letters of dismission, November 1859, page 616; digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9XF-HND7?i=610: accessed 2/4/2023); image 611 of 694. Note: Records abstracted at https://theyhadnames.net/midway-church-records/. ↑

- Charles Green testified to U.S. Southern Claims Commission officers in 1872 that he had purchased Samuel A. McIver prior to the Civil War. “U.S. Southern Claims Commission, Allowed Claims, 1871-1880,” Chatham County, Georgia, case file of Samuel A. McIver, case #6609; indexed digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1217/images/RHUSA1871A_118415__0023-00888 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 42 of 257. ↑

- “U.S. Southern Claims Commission, Allowed Claims, 1871-1880,” Chatham County, Georgia, case file of Samuel A. McIver, case #6609; indexed digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1217/images/RHUSA1871A_118415__0023-00888 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 1 of 257. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid, image 18. ↑

- This does not appear to have been true, as Green seems to have been in Savannah at this time. General Sherman wrote in his memoirs, “While waiting there, an English gentlemen, Mr. Charles Green, came and said that he had a fine house completely furnished, for which he had no use, and offered it as headquarters. He explained, moreover, that General Howard had informed him, the day before, that I would want his house for headquarters.” General William T. Sherman, Sherman’s Memoirs, pp 494-495. ↑

- “U.S. Southern Claims Commission, Allowed Claims, 1871-1880,” Chatham County, Georgia, case file of Samuel A. McIver, case #6609; indexed digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1217/images/RHUSA1871A_118415__0023-00888 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 18 of 257. ↑

- ↑

- The SCC investigator, R.B. Avery, interviewed one Grant Simpson, who testified under oath on May 16, 1878, that he had never known of McIver owning a horse and wagon prior to the arrival of the U.S. army. “U.S. Southern Claims Commission, Allowed Claims, 1871-1880,” Chatham County, Georgia, case file of Samuel A. McIver, case #6609; indexed digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1217/images/RHUSA1871A_118415__0023-00888 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 38-39 of 257. ↑

- Ibid, image 3. ↑

- Ibid, image 42. ↑

- Ibid, image 25. ↑

- “Savannah, Georgia, U.S. Registers of Free Persons of Color, 1817-1864,” Chatham County, Georgia, volume 6, 1860-1863, listings for Margaret and Matilda Mciver, 1861; digital database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8969/images/42454_331858-00242 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 31 of 47; citing City of Savannah, Research Library & Municipal Archives, Registers of Free Persons of Color, Roll: 5600cl-130-02, volume 6, 1860-1863. ↑

- For more about the immediate postwar history of the Midway Congregational Church, see https://theyhadnames.net/midway-church-sessions-1865-1867/ and Stacy, History and Published Records of the Midway Congregational Church, Liberty County, Georgia. ↑

- For McIver’s and Goulding’s petition to the Church, see “Midway Congregational Church Records,” quarterly session records, Liberty County, Georgia, 1762-1867, Sam McIver and Tony Goulding petition, August, 1867; unindexed digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9XF-HNZB: accessed 2/4/2023); image 637 of 694. ↑

- “U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878” -> “Superintendent of Education”-> “M799” -> “28,” “Delegates to the Georgia Educational Convention held in Macon, May 1-2, 1867”; indexed digital database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/3625889:62309 : accessed 2/5/2023), image 123 of 154. ↑

- “Georgia, U.S., Property Tax Digests, 1793-1892,” Liberty County, Georgia, 1878-1885, District 15, entry for Samuel A. McIver, 1880; digital database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1729/images/40881_1220705227_0839-00677 : accessed 2/4/2023), image 536 of 702. ↑

- Liberty County, Georgia, Deeds and Mortgages, 1884-1885, Book U, pages 193-4; digitized microfilm accessed through catalog, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-R9D5-L: accessed 2/4/2023), Family History Library microfilm 008564336, image 378 of 593, item 1 of 2; citing original records of Liberty County Superior Court, Georgia. ↑

- This article refers to McIver’s seeking a new wife. Margaret McIver was also not listed with McIver in the 1900 census. The Augusta Chronicle (Augusta, Georgia), November 3, 1889 edition, page 3. ↑

- The 1915 death certificate of Matilda’s daughter, Margaret J. Roberts, listed her parents as Matilda McKiver and Seaborn Proctor. “Georgia, Death Index, 1914-1940,” entry for Margaret J. Roberts, March 25, 1915, Savannah, Chatham County, Georgia, State File 6661; database images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2562/images/004178777_00237 : accessed 2/5/2023), image 237 of 1519. ↑

- “Savannah, Georgia, U.S. Cemetery and Burial Records, 1852-1939,” Laurel Grove Cemetery interments, 1870 Jan-1878 Sep, entry for Matilda Proctor, Sec C, date of death July 15, 1876, date of burial July 15, 1876, 41 years old; indexed digital database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2770/images/40153_B013355-00449 : accessed 2/5/2023), image 444 of 632. ↑

- 1880 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, District 15, enumeration district 66, page 12 (handwritten), dwelling 122, family 124, entry for Samuel A. and Margaret McIver household; digital database, Ancestry https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6742/images/4240148-00368: accessed 2/4/2023), citing NARA microfilm publication T9, roll 155, page 6D. ↑

- Journal of the Georgia General Assembly, House of Representatives, November 1888, pages 242-244. Also see Savannah Morning News, November 6, 1888, page 2, and Savannah Mornings News, October 30, 1888, page 8. ↑

- George A. Rogers and R. Frank Saunders, Jr., Swamp Water & Wiregrass: Historical Sketches of Coastal Georgia,” (Macon, Georgia : Mercer University Press, 1984), page 118. ↑

- The Augusta Chronicle (Augusta, Georgia), July 26, 1889 edition. ↑

- The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), September 5, 1889 edition, page 2. ↑

- Savannah Morning News (Savannah, Georgia), October 26, 1889, edition, page 3. ↑

- Margaret and Joseph Roberts were married in Liberty County, Georgia, on February 7, 1900. “Georgia, U.S. Marriage Records from Select Counties, 1828-1978” -> “Liberty” -> “Marriages (White and Colored), Book B, 1897-1909,” marriage entry for Joseph Roberts and Miss Margaret G. Proctor, February 7, 1900; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/4766/images/40660_307901-00276 : accessed 2/5/2023), image 104 of 276. ↑

- 1900 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, Militia District 1476, enumeration district 88, sheet 1, line number 1; digital database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7602/images/4120072_00095: accessed 2/4/2023), citing Family History Library microfilm 1240209. ↑