Ever have an item on your “to-do” list that stays there for years because you know it will open up a time-consuming can of worms?

I got to cross one of those off recently. Not because I did it. Because it turns out it didn’t need doing.

Several years ago I ran across an article in the Liberty County Coastal Courier that claimed the existence of antebellum Liberty County tax records that contained the names of enslaved people. The only antebellum tax records for Liberty County I’ve found online (at FamilySearch and Ancestry) are tax digests, which give numbers of enslaved people but no names.

Records with names would be an absolute gold mine.

I poked around a bit. The article mentioned Sampie Smith, who at the time was the “Hinesville archivist,” according to the article. I tried to see if I knew anyone who knew him and could put me in touch with him. No luck. I called the Courthouse. They said tax records would be with the tax authority.

I knew that if these records existed, they would need to be digitized. FamilySearch will digitize records like that for free, but it’s a time-consuming process to get all the necessary local permissions.

I’m embarrassed to say I put it on my “to-do” list and moved on. Every so often I’d look at it, languishing there on the to-do-list, silently reproaching me…and I’d move on to the next project.

Finally, finally, I decided it must be done. In the meantime, Sampie Smith had died. Before I approached the tax authority, I re-read the article to remind myself the details about the records.

That’s when I realized the records don’t exist. The article was mistaken. It showed two images. One was indeed a tax record, but it listed only the aggregate number of people being held in slavery and their value — no names — just like the ones online.

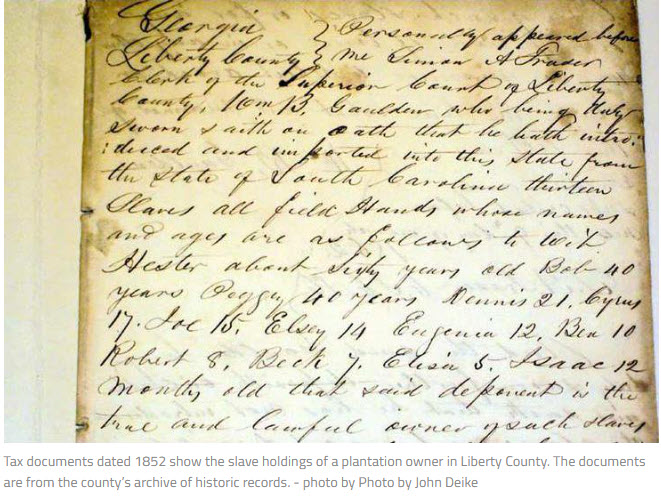

The other image did name enslaved people but it was not a tax record, even though the caption claimed it was. It was an 1852 Liberty County Superior Court record. William B. Gaulden — a complex, controversial figure in Liberty County history — had executed a document stating that he had brought the following enslaved people into Georgia from South Carolina: Hester, about 60 years old; Bob, 40 years old; Peggy, 40 years old, Dennis 21; Cyrus, 17; Joe, 15; Elsey 14; Eugenia, 12; Bea, 10; Robert, 8; Beck, 7; Elisa, 5; Isaac, 12 months. (Image below is a snapshot of the record from the Coastal Courier website with their original caption.)

So I can check this task off the to-do list, right? I was a little sad about that because if there had been tax records with names, they really would have been an amazing resource. But I have plenty of other things to do.

First, though, I needed to make sure I have that record in my database. I have previously gone through the Superior Court deed records and abstracted all the ones that contain the names of enslaved people, so I checked to see if I have this one. I do not. I do have a record that William B. Gaulden purchased these people from the executors of James David Mongin’s estate and paid for them over time, using them as collateral for payment of the purchase price. I checked the link for that one to make sure I didn’t just miss this record in the series of records about that sale. It wasn’t there.

Why would Gaulden have needed to swear that he had brought these people into Georgia from South Carolina? Imported enslaved people from Africa to the United States was banned in 1809 so interstate transfers needed to be recorded to prove that they had not been illegally imported. Obviously, those records are hugely valuable, and I have not found many of them.

So where might this one be? The genealogical arm of the Church of the Latter Day Saints (now known as FamilySearch.org) long ago digitized county court records across the United States. They can also be found on Ancestry. They have nine digitized record sets for the Liberty County Superior Court. One contains the deed records I have already processed, so we can set that aside. Six others either don’t cover the right time period or contain unrelated records (divorces, land surveys and grants, etc).

Of the two remaining sets, one contains Court proceedings from 1826 to 1922, and the other contains Court minutes from 1784 to 1935. In fact, these record sets are also on my to-do list and I have completed the time periods 1804-1865 for the minutes and 1842-1864 for the proceedings, so in theory I would have already found it if it was there. I checked again just to be sure. No luck.

Where else could it be? Most courthouses have what are called “loose records.” For example, there might be a folder for William B. Gaulden into which would be stuffed various records that applied to him. In Liberty County, there are two sets of these online at FamilySearch: one for records pertaining to estates (Administration records) and another that has all kinds of records, including many criminal court records (misnamed Estate records). There are tens of thousands of pages of images in those records, so I have only gone through a few folders as I’m researching particular people.

Fortunately, there are typed indexes scattered through the images, and I’d previously made a working aid for those so I could check quickly for Gaulden records. There were none.

So what does this mean? Either I missed it in the deed records or there’s another set of records at the courthouse that hasn’t been digitized. I’m trying to think of a third possibility because both of those seem unlikely, but haven’t come up with anything yet. (It’s not unlikely that I could have missed it but I’d expect it to be with the sale records in the deed book and it’s not.)

Looks like I have a new to-do list item: visit the courthouse with a copy of the image to see if I can find it. At least I know it’s an 1852 Superior Court record.

Lesson learned: read everything carefully! If I had looked more carefully at those images, I could have come to this conclusion years ago.