The Liberty County Martin Luther King Jr Observance Association put on a wonderful series of events in January. During their awards ceremony, Flanders Pray, a freedman who was one of Liberty County’s first African American teachers after the Civil War and an inspirational community leader, was given the Lifetime Achievement Award. A large group of his descendants accepted the award on his behalf, and to my complete surprise, the family called me up to the stage to give me their own award for the research I did to uncover additional details of his life. I was so moved by their kindness and thoughtfulness.

Thank you to my good friend Hermina Glass-Hill, executive director of the Susie King Taylor Women’s Institute and Ecology Center and president of the Liberty County Historical Society, for taking this photo of the Flanders Pray family and me at the awards ceremony!

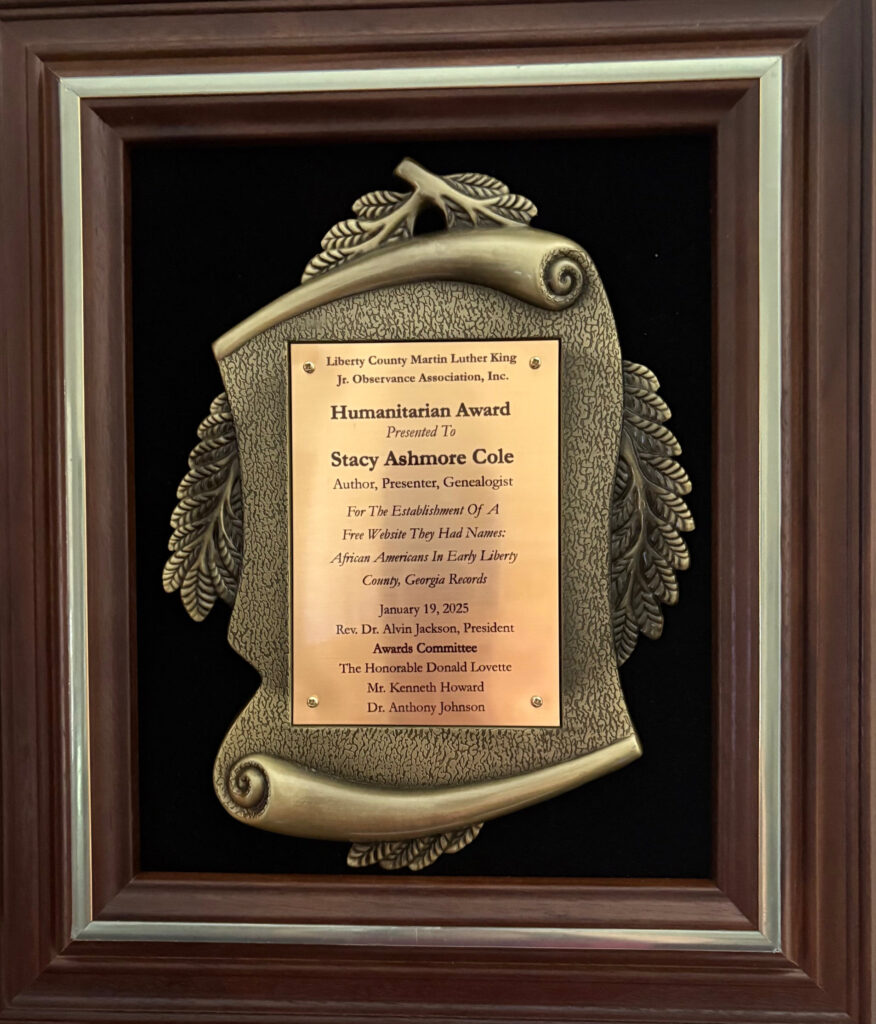

I was there to receive the Association’s Humanitarian award for my work on the They Had Names website. I am deeply grateful to Liberty County Chairman of the Board of Commissioners Donald Lovette, who put me in for the award. This is by far the most meaningful of the awards the website has received, because it came from descendants of the people whose names are in the records that TheyHadNames.net memorializes.

So what’s the plan for the website in 2025? Well, first and foremost is preparing the major record sets to be put into downloadable books. I turned 66 last year. You may also have noticed that there’s a new administration in Washington. It’s time to start making sure that the work put into the website cannot just disappear. I’m currently compiling the estate inventory records, and hope to have free, downloadable PDF versions on the website within the next six weeks. There will probably be four books of those because of the volume of those records.

Next will come the wills and the deed records, then other records. For example, I have a list of 1100+ enslaved and free African Americans who were full members of the white Midway Congregational Church from 1756 to 1867, as well as more than 70 fully transcribed Southern Claims Commissions petitions, a large number of which were made by freedmen and women in Liberty County.

I plan to apply for grants to put these books in Georgia libraries. The website itself is included in a Library of Congress project to make available small sites like mine in perpetuity. Unfortunately, I now worry about the “in perpetuity” part of that, given events in Washington. The International African American Museum in Charleston has reached out to me about hosting my data (which would be in addition to my site, not instead of it) so that may be a possibility, and I’m continuing to investigate other ideas for making the work sustainable in its current form as a searchable database.

The books will at least ensure availability for the immediate future. I hope to have them all done by the end of the year.

The Flanders Pray research made me realize that Bryan County’s records are an integral part of Liberty County’s history, since many of the enslavers from both counties were intermarried. Flanders Pray was a prominent community leader in Liberty County, but he and his family were held in slavery in Bryan County. Bryan County’s probate records (wills and estate inventories) from before the Civil War seem to have disappeared, but the deed records (bills of sale, chattel mortgages, deeds of gift, marriage contracts, etc) remain. Last year I started work abstracting all the Bryan County deed records that name enslaved people and have completed the records from after the Revolution to 1854, with more than 2500 references to named enslaved people. I’ll complete the rest (through 1865) over the next few months, and that will also become a downloadable book.

I’ve been engaged during the past few months creating a list of all the known enslavers from Liberty County. After going through census records, I now have 583 enslavers on the list, and there are many others to add who were named only in documents between censuses or in colonial records.

As the work progresses, I plan to correlate the names with the records I have, with the goal of making it much easier for descendants of people held in slavery in Liberty County to break through the 1870 barrier to find the enslaving families, which unfortunately is necessary to uncovering their family histories.

Right now users of the website have to do those correlations themselves because of the difficulty I’ve had in distinguishing between enslavers of the same name. I hope it will become possible to link the records to the correct slaveowner as a result of having the list.

A central goal of that project is also to link names on the 1870 census to their last enslaver. Thanks to the work of Dr. Peggy Hargis, retired from Georgia Southern University, we already have that information for about 275 freedpeople, based on Southern Claims Commission records. I hope to extend this to hundreds more.

Of course, I’ll still be happy to help any descendants who reach out for assistance in putting the records together to find their family histories.