Have you heard of FamilySearch’s experimental search feature that allows searching the full text of U.S. county land, probate and court records? It’s definitely a game-changer but how well is it working now in November 2024?

I have a website where I put abstracts of Liberty County, Georgia, records naming enslaved people. I’ve gone page by page through through all the antebellum Liberty County deed, wills and estate inventory records available on FamilySearch, abstracting any relevant records, so I used my very large data set to see if the full-text search would find these records I already knew existed.

To learn how to use the full-text search and get some great examples

of its usefulness, check out

Jennifer Dunn’s Copper Mine Genealogy short Youtube video:

https://youtu.be/KE7065tCaPI?si=XMncNiGMgxBpPUFr.

I chose at random 20 deed records I had already abstracted. Here’s an example from the website:

Enslaved Persons Named: Tom, Bess, Affy, Jacob, Nancy

Type: marriage contract

On May 30, 1822, Mary Ann Girardeau and Benjamin Fuller entered into a marriage contract, with Major Andrew Maybank as her trustee, all of them in Liberty County. As part of the contract, the following were put into trust for Mary Ann Girardeau: “personal property, namely, to one negro man slave, named Tom, one negro woman slave named Bess, one other negro woman slave named Affy, one small negro boy slave named Jacob, and one other negro woman slave named Nancy…” Witnessed by John Girardeau, and William P. Girardeau, who probated it on May 17, 1823. Recorded in Liberty County Superior Court on May 29, 1823.

Source: Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, 1822-1831, pp. 40-1. Image #322 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSRC-5)

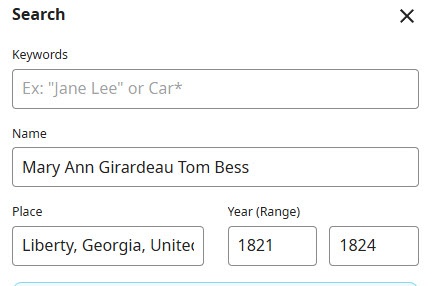

Then I searched for this record in the FamilySearch labs experimental section, selecting a couple of the enslaved people’s names to use as search terms:

(I also tried putting Tom and Bess in the keyword section and it worked equally as well.)

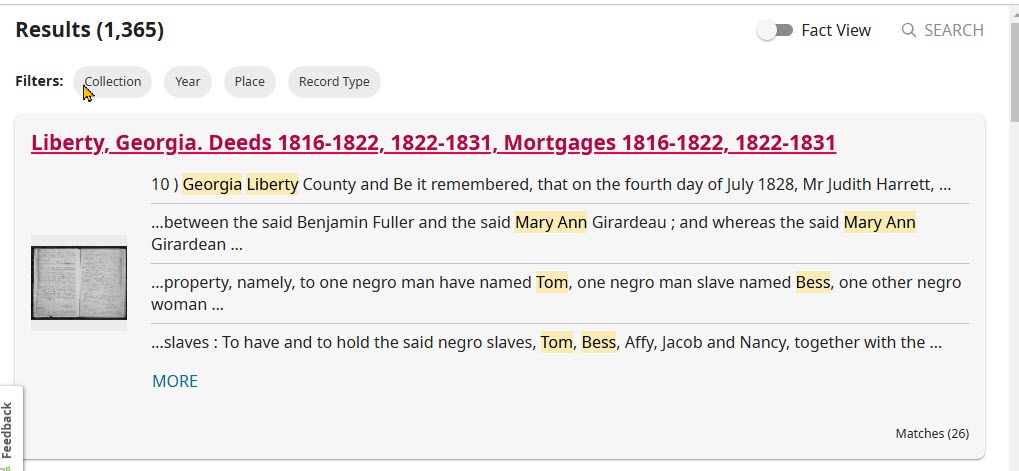

Success! It was the first record in the results:

How well did it transcribe the record?

Whereas & marriage intended to be shortly had and solemnized between the said Benjamin Fuller and the said Mary Ann Girardeau ; and whereas the said Mary Ann Girardean is entitled to a steen estate , consisting of personal property , namely , to one negro man have named Tom , one negro man slave named Bess , one other negro woman slave named Afty , one small negro boy slave named Jacob , and one other negro woman slave named Nancy

Mary Ann Girardeau’s surname was transcribed correctly the first time, but not the second time. Of the five enslaved people, Affy’s name was mistranscribed (Afty).

When I tried the search again, this name using the name “Affy” instead of “Tom” and “Bess,” the record was not found, so the search algorithm does not appear to be searching for variants.

The errors are not at all surprising. It is actually amazing that it got so much correct. A year ago, I would have said that we wouldn’t see this kind of automated transcription of handwritten documents in my lifetime.

But if you’re looking for Affy, you’re not going to find this record this way.

Results with the other records I tried were similar. Overall, the full-text search with handwritten, relatively clean documents written in paragraph style was successful with about 85% of the names of the enslaved. When I threw in a more faded document and one that had handwriting over the top of the document (stating that the mortgage had been satisfied), the success rate was closer to 45% and 25%, respectively.

This is much better than I had expected, but still worrisome if you are looking for the names that were mistranscribed.

Using the full-text search on columnar data — in this case, estate inventories — was a complete failure. I wasn’t surprised that it couldn’t handle the columns, but the mistranscription rate also rose dramatically. Less than half of the names were transcribed correctly in one example, and less than one-third in another.

The lesson?

I count FamilySearch’s full-text transcriptions as one of the great blessings in genealogy. It has made it possible to find your ancestor whether s/he was a witness in a record or in a county you weren’t expecting. I hope it will continue to improve.

But you probably won’t be surprised to learn that for now, you’re still going to have to go through the record set page by page to make sure you’ve found everything, and for descendants of enslaved people, who are searching for a first name only, the task is harder still, as always.