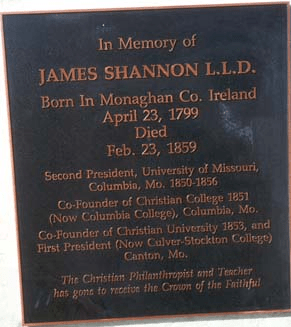

Reverend James Shannon, who immigrated from Ireland to Liberty County, Georgia, in 1820, was an influential clergyman, educator and college administrator in Georgia, Louisiana, Kentucky and Missouri. His early experiences in Liberty County, where he married a woman who had inherited enslaved people, resulted in his becoming an outspoken and fiery proponent of slavery.

As head of the University of Missouri at Columbia and the first president of Culver-Stockton College in Missouri, his pro-slavery advocacy propelled him into the heart of the debate over slavery in the border states before his death in 1859.

Documents about his life reveal the names of the people he held in slavery, some of whom were forced to leave Liberty County and accompany him in his travels.

Throughout his adult life, he was both an academic and a clergyman. A Presbyterian when he came to the United States, he became a Baptist a few years after arrival, and then a leader in the Disciples of Christ movement.

Shannon was part of the impetus behind the establishment of Mercer College in Georgia and was chair of Ancient Languages at Franklin College (later University of Georgia) in 1830. He became Dean of the College of Louisiana, President of Bacon College in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, and head of University of Missouri at Columbia.

He helped establish Christian Female College in Missouri (now Columbia College) and was the first president of Christian University (now Culver-Stockton College) in Missouri, where he died in 1859.[1]

Immigration to Liberty County, Georgia

Shannon, born in Monaghan County, Ireland, in 1799, traveled aboard the brig George from Belfast to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1820.[2] Educated at the University of Belfast,[3] he had been recruited by Dr. William McWhir, a very well known educator and Presbyterian clergyman of the time, to teach at the Sunbury Academy in Liberty County, Georgia. Dr. McWhir paid his passage to Georgia, and apparently had traveled to Ireland to recruit him, as he accompanied him on the passage to America.[4] The two later fell out after Shannon, originally a Presbyterian, became a Baptist shortly after arrival.[5]

Dr. McWhir was a fellow Irishman who had moved to the United States at the end of the Revolutionary War. He had married a well connected, local woman from whose enslaved property he derived a major portion of his livelihood. He was known for his strict physical discipline of school children.[6] Dr. McWhir and Rev. Shannon had many similarities: both Irishmen, clergymen, and prominent educators of their time who married women who brought enslaved people into their personal lives.

Marriage to a Slaveholder’s Daughter

In 1823, James Shannon married Evalina Dunham, whose birth to Charles and Ann Dunham in 1797 had been recorded in the local Midway Congregational Church.[7] Their marriage was not recorded in Church records, even though Evalina had become a member just the year before,[8] presumably because Shannon had become a Baptist while in Sunbury, though he arrived as a Protestant. The Dunham family had deep roots in Liberty County and held extensive enslaved human property. Liberty County had been named for its spirited support of the American Revolution, and had been settled in the mid 1750s by European-descended planters from mostly South Carolina, who came when the Province of Georgia legalized slavery, bringing with them a culture steeped in use of enslaved humans.

In October 1823, Shannon and Evalina entered into a marriage settlement, with Col. Joseph Law and Major Samuel S. Law as her trustees.[9] The Law family were prominent Baptists in Sunbury and are believed to have been instrumental in Shannon’s conversion.

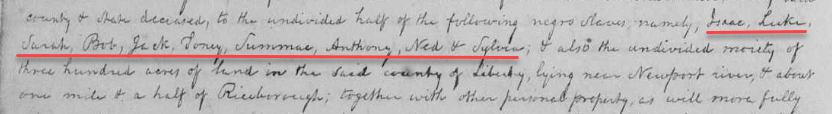

The settlement noted that under the last will & testament of her Aunt Martha Carter,[10] she was entitled to the undivided half “of the following negro slaves namely, Isaac, Luke, Sarah, Bob, Jack, Toney, Summer, Anthony, Ned & Sylvia, and also the undivided half of a 300-acre tract of land in Liberty County, lying near the Newport river & about one mile & a half from Riceborough (Riceboro), the county seat at the time.

In the settlement, Shannon committed to turn over any property Evalina had or would receive in the future to the trustees upon and after their marriage. They agreed that she would have the use and benefit of the property during her lifetime and that any children she might have would inherit. Often these settlements contained a clause stating that if the woman did not have children and predeceased her intended husband, he would inherit, but this settlement did not contain that clause.

Martha Carter, nee Martha Dunnom (another spelling of Dunham), had died earlier that year. After giving an enslaved girl named Rachel to her grand-niece, Amanda Mara, she left the remainder of her estate to her niece Evelina Dunham and her nephew William C. Way. James Shannon had been one of the witnesses to the will.

Martha Carter expressed the desire that “the negroes be kept together on the plantation where they now are, unless one of both of the parties should marry, and wish a division, which shall take place only with the consent, and at the discretion, of the Trustees.”

Martha Carter’s estate was appraised later that year, and included the following people being held in slavery: Anthony, Chloe, Sary, Patience, Summer, Jack, Toney, Derry, Rachel, Patty, Jacky, Luke, Pricey, Ned, Sylvia, Little Chloe, Bob, and Isaac.[11]

At the time of Evalina’s marriage the estate would have been divided, and this revealed more information about the history of these enslaved people. It appears that they were to be held by Martha Carter only during her lifetime, and in fact had been the property of her husband James Carter. Thus the division of her estate occurred under his name in late 1823, and William Way and Evalina Dunham together drew lot #1: Isaac, Luke, Sarah, Bob, Toney, and Summer. Anthony, Ned and ⅗ of Sylvia were not part of the division but evidently ended up with Evalina Dunham.[12]

It was noted in the division that care had been taken not to separate families; however, this was apparently not entirely successful because James Shannon purchased Chloe, a 45-year-old woman said to be Anthony’s wife, from Ann E. Mara.[13] In addition, Ann E. Mara inherited ⅖ of Sylvia; presumably the other ⅗ were inherited by William C. Way and Evelina Dunham.

James Carter’s estate was first appraised in 1804, presumably shortly after his death, and the names Prince, Toney, Isaac, Rachel, Chloe, Luke, Sary, Patience, and Patty appear in it, among others.[14] The others were likely born after that. In his will, he gave his wife Martha an undivided half of his enslaved people with the other half to his nephew James Carter Bowles [or Bowler] and to Ann Peacock.[15]

The marriage settlement between Evalina Dunham and James Shannon was a way of preserving for her the ownership of the property she brought into their marriage, though it technically now belonged to her trustees. She also only owned the undivided half of these people, the other half being owned by William C. Way. The “undivided half” meant that she and William Way each owned half shares in the entire group.

Given that Evalina did not own these people outright, and with Rev. Shannon being newly arrived in the United States, it is likely that he did not assume their management at that time.

Shannon Embraces Slavery

In 1826, Shannon purchased Peggy, Rose, Bella, David and Derry from Samuel S. Law, one of Evalina’s trustees, in two transactions,[16] and Tamar from William Ward.[17] He would have owned these people outright, rather than through his wife.

A copy of the Shannon family bible was obtained from the State Historical Society of Missouri (SHSMO) and it had the birth dates of the people he held in slavery.[18] There were 12 people listed whose births occurred before Shannon married Evalina, and many of their names match the people she inherited and that he purchased:

| Name | Birth Date | 1823 marriage settlement | 1826 purchase by Shannon | 1826 Martha Carter estate division | 1804 James Carter estate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloe | 1777 | Chloe | Chloe | ||

| Isaac | 5/1789 | Isaac | Isaac | Isaac | |

| Luke | 8/19/1793 | Luke | Luke | Luke | |

| Dary [Derry] | 12/29/1797 | Derry | Derry | ||

| Sampson | 11/2/1802 | ||||

| Jack | 7/30/1808 | Jack | Jack | ||

| Toney | 9/3/1810 | Toney | Toney | ||

| Bob | 12/1821 | Bob | Bob | ||

| William | 3/1824 | ||||

| Hannah | 9/5/1824 |

Teaching School in Georgia

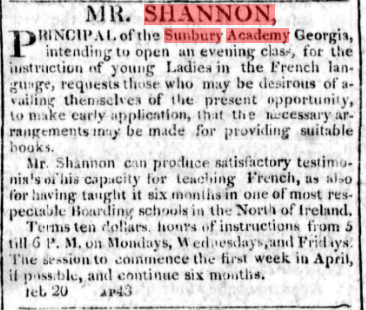

Shannon appeared to have become the principal of Sunbury Academy in 1822, as he began sending advertisements to Savannah newspapers.[19]

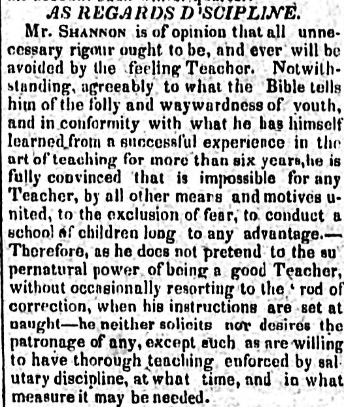

In 1826, Shannon, describing himself as the “late principal of the Sunbury Academy,” advertised in a Savannah newspaper that he was planning on opening a “Classical and English Seminary” in Augusta, Georgia for both female and male instruction. He devoted a lengthy section of the advertisement to explaining that he did not want any patrons who would not allow their children “to have thorough teaching enforced by salutary discipline, at what time, and in what measure it may be needed,” adding that he was convinced that it was impossible for any teacher “by all other means and motivated united, to the exclusion of fear, to conduct a school of children long to any advantage.”[20] He stated in the advertisement that he had been principal of Sunbury Academy for four years.

As with Dr. McWhir, his strict physical discipline (“spare not the rod”) raises the question of whether he would have been any less discipline-oriented toward the people he and his wife held in slavery. Although that kind of discipline may have been common at the time, it is noteworthy that he felt the need to discuss it at length in a paid advertisement and to warn parents not to bring him their children unless they were willing to accept it, implying that some, at least, would not be willing. In Dr. McWhir’s case, his cane is still held in a local museum, and a student of his who later became a well known clergyman, Rev. Charles Colcock Jones, commented that his discipline was considered somewhat excessive even for the time.

Move to Augusta, Georgia

In 1826, Shannon had been called to become pastor of the Augusta Baptist Church, presumably the reason he moved to Augusta.[21] Upon the resignation of their current pastor, Dr. Brantly, the Augusta Baptist Church had offered Rev. Shannon a salary of $1200 per year, “being at the time probably the largest salary paid to any minister in the State.”[22]

During his time at Sunbury and in Augusta, Rev. Shannon apparently was influential in the education and mentoring of many students who later became prominent Baptist ministers in Georgia.[23]

Although he was now resident in Augusta, fifteen people being held in slavery by him remained in Liberty County, where they were enumerated under his name in the 1830 census, which did not provide their names.[24] It seems that he likely left the people inherited by his wife and William C. Way on the plantation where they had been living.

Given the previous records, it would have appeared likely they were Isaac, Luke, Sarah, Bob, Jack, Toney, Summer, Anthony, Ned, Sylvia, Peggy, Rose, Bella, David, Derry, and Tamar: the 10 people his wife inherited from her aunt, the four he bought from her trustee, and the woman he bought from William Ward.

However, the 1830 census described these people as follows and the genders do not match:

-4 boys under the age of 10

-2 youths between 10-23

-3 men between 24-35

-2 men between 55-99

-1 girl under the age of 10

-2 girls between 10-23

-1 woman aged 36-54

Without further records, this discrepancy has to be left as it is for now. It is likely there were other transactions that may not have been recorded in court.

Shannon paid taxes in Augusta, Richmond County, from 1826-1829 but his only property was listed as being in Liberty County.[25]

Move to Athens, Georgia, and Further Dealings in Slavery

In 1830, Shannon and his wife were in Athens, Clarke County, Georgia.[26] Shannon had become the chair of Ancient Languages at Franklin College of the University of Georgia[27].

According to census records, two young White men between the ages of 20-29 were living with them, and they now had a child, presumably their daughter, under five years old. They also had with them two enslaved men, aged 10-23 and 55-99, and three enslaved women between the ages of 10-23, 36-54, and 55-99. It seems very possible that these are the people James Shannon purchased from Samuel S. Law in 1826: Bella, David, Derry, Peggy and Rose.

In 1832, James Shannon sold Tamar (previously purchased from William Ward) and Peggy (inherited by his wife) to the children of Benjamin King of Twiggs County: William Thomas King, James Benjamin King, and King’s stepdaughter Hetty W. Cauley, to be held by their trustee James C. Bryan of Twigg County. The purchase was recorded in Liberty County Superior Court.[28]

An 1834 record likely revealed the names of the people inherited by Evelina after division of her aunt’s estate.[29] Her co-inheritor, William C. Way, used the people who had been divided to him as security for James Shannon on a promissory note made by his brother, Joseph Shannon of Richmond County, Georgia. Shannon was standing as security for Joseph’s note, and Way was backing him up in case of default.

Way said in that record that the following people had been divided to him of the people co-inherited from Martha and James Carter: Isaac, Jack, Ned, Sarah and her child Bob, “together with all the increase or children of Sarah.” Since Isaac, Luke, Sarah, Bob, Jack, Toney, Summer, Anthony, Ned & Sylvia were the people co-inherited, this appears to indicate that Evelina’s portion was Luke, Toney, Summer, Anthony and Sylvia. The record was recorded in Richmond, Clarke and Liberty Counties.

Now Head of College of Louisiana and Loss of His Wife

Between 1835 and 1840, Shannon lived in Jackson, East Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, where he was in charge of the College of Louisiana (now Centenary College).[30] His wife, Evelina, carried on correspondence with friends left behind, and one of those letters, to Frances Carey Moore on February 18, 1836, carried news of some of the enslaved people who had accompanied them there. She wrote, “Tell Grandmother Smith she has made a case of Mima [or Mimy]. She has not been sick but once since we left Athens, and then she had the mumps. She hires out by the day at [amount]…there has not been any sickness among black or white since we have been in the place…Tony says tell Miss Frances to tell his father and mother howde [howdy] for them all that he has a son and has called him Anthony.”

Despite her talk of how healthy the climate was, Evelina died in Jackson later in 1836,[31] and in 1837 James Shannon married her friend Frances Carey Moore.[32]

The 1840 census listed Shannon as owning one male child under 10 years old, one man aged 24 to 35, another man aged 36 to 54, a girl aged 10 to 23, and a young woman aged 24 to 35.[33] The male child under 10 years old was presumably Tony’s son Anthony, mentioned in Evalina’s letter, and the young man and woman aged 24 to 35 were presumably Anthony’s parents.

Shannon appeared to have continued to have business in Georgia. While resident in Louisiana, on June 29, 1837, Shannon gave his brother, Joseph Shannon, who was living in Richmond County, Georgia, power of attorney to conduct any business necessary for him in the State of Georgia. One Charles Dougherty signed the power of attorney as witness.[34] On January 1, 1840, James Shannon revoked this power of attorney in Athens, Clarke County, still citing his residence as Louisiana and stating that Joseph Shannon was “formerly” of Richmond County.[35] The same day, he signed power of attorney over to Charles Doughterty of Clarke County.[36]

Moving West to Kentucky and Missouri

In 1840, Shannon became president of Bacon College in Harrodsburg, Mercer County, Kentucky, and remained there until 1850, when he moved to Columbia, Boone County, Missouri to become president of the University of Missouri at Columbia.[37] While there, he helped establish the Christian Female College (now Columbia College). He and Frances were there for the 1850 federal census, where he was listed as owning the following 14 people, identified only by gender and age:[38]

Man aged 61

Woman aged 53

Man aged 40

Man aged 28

Man aged 26

Woman aged 30

Man aged 17

Girl aged 14

Boy aged 10

Girl aged 8

Boy aged 6

Girl aged 5

Boy aged 3

Girl aged 1

Shannon was a controversial figure, given his adamant pro-slavery views and the climate in Missouri at the time. He was said to have claimed during a speech, “Convince me that slavery is a moral wrong, and I pledge myself to preach infidelity all the rest of my life and to prove that God is an imposter.”[39] A newspaper stated about him, “…forgetful of all his ministries–careless of the one college which he had ruined, and the other which he is fast destroying–regardless of his half-finished scriptural commentaries, and unmindful of the proprieties of his station, he has launched into the sea of bitter politics.”[40]

One newspaper possibly revealed the fate of one of the enslaved men inherited by Shannon’s wife. In 1854, a staunchly anti-slavery (and anti-Shannon) newspaper described Shannon as follows: “James Shannon, President of the State University, (and as much the owner and master of Adams Peabody, ostensible editor of the Journal, as he is the owner and master of Tony, the colored bell-ringer of the College)…”[41] Tony could have been the Tony who sent greetings to his parents and announced the birth of his son Anthony via Evalina’s letter to Frances Carey Moore in 1836.

In 1856, Shannon declined reappointment as the president of the University of Missouri, and was given an honorary LL.D. degree.[42] Shannon became instead the first president of the Christian University (now Culver-Stockton College) in Canton, Lewis County, Missouri. In 1858, however, the University’s trustees “suspend[ed] their control of the business of Instruction by the general failure of the subscribers to the endowment fund to pay their accruing installments as they fell due,” forcing Shannon, as president, and other faculty members to open classes “on their own responsibility.”[43]

Shannon was active in fields other than the ministry and academia. In 1858, he was appointed secretary of the stockholders of the Southern Pacific Railroad at a meeting in Louisville, Kentucky.[44]

He died in Missouri, at the age of 59 in February 1859, and is buried there in Columbia Cemetery in Columbia, Boone County.[45]

In March 1859, because Shannon had died without a will, Alexander Douglass and Walter S. Lenoir were appointed administrators of his estate.[46] It can be assumed that they conducted an estate inventory and appraisement and there should be further paperwork related to this. However, it seems likely that his wife, Frances Carey Moore Shannon, would have inherited or managed his estate for his children, who were all minors at his death. She died just before the end of the Civil War, on March 16, 1865, and is buried in the same cemetery[47]. Because of the timing of her death, any surviving probate papers are unlikely to have named enslaved people.

Liberty County, Georgia, was where James Shannon first encountered slavery in a personal sense, rather than as a theory. His experiences there likely informed the opinions he espoused so passionately throughout his life. To the extent that he influenced the march toward civil war, it is worth knowing that his formative period was in Liberty County.

There is much further research to be done to determine what happened to the people held in slavery by James Shannon.

Avenues for further research:

- Louisiana probate documents for Evalina Dunham (including a May 22, 1839, record of a Shannon family meeting regarding the estate, recorded in Book H, pages 34-35 – apparently not available online)

- Were enslaved people brought into the marriage by Shannon’s second wife, Fanny?

- Documentation of the names of the the people he held in slavery in Missouri

- Any probate records for James Shannon in Missouri that named enslaved people

- What happened to them at Emancipation?

My thanks to Kevin George, senior librarian, Center for Missouri Studies, The State Historical Society of Missouri, who kindly went well out of his way to assist me in finding the Shannon Family Bible and family letters.

FOOTNOTES

- Biographical Sketch of Dr. James P. Shannon by Scott Harp, “History of the Restoration Movement” website, https://www.therestorationmovement.com/_states/missouri/shannon.htm (accessed 28 Oct 2024). ↑

- The National Archives, Washington, D.C., Copies of lists of passengers arriving at miscellaneous ports on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and at ports on the Great Lakes, 1820-1873, series number M575, Record Group 287, passage for James Shannon (22) and Wm. McWhir (64) aboard the Brig George; database with images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8758/images/USM575_2-0041 : 28 Oct 2024), “U.S., Atlantic Ports Arriving and Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1959” -> M575-Atlantic, Gulf and Great Lakes, 1820-1873” -> Roll 2, image 41 of 792. ↑

- “James Shannon’s Search For Happiness,” Missouri Historical Review, Volume 73, Issue 1, October 1978, pp 71-84; State Historical Society of Missouri (SHSMO) digitized collections ((https://digital.shsmo.org/digital/collection/mhr/id/38153 : accessed 28 Oct 2024). ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Harrell, David E., “James Shannon: Preacher, Educator, and Fire-Eater,” Missouri Historical Review, January 1969, pp. 135-170 (https://digital.shsmo.org/digital/collection/mhr/id/32333 : accessed 9 Oct 2023). ↑

- For more about Dr. McWhir, see “Slaveholder Series: William McWhir,” by Stacy Cole, blog post on the They Had Names website (https://theyhadnames.net/2021/03/29/slaveholder-series-william-mcwhir/ : accessed 10 Oct 2023). ↑

- James Stacy, History and Published Records of the Midway Congregational Church, Liberty County, Georgia, The Reprint Company, Spartanburg, South Carolina, 2002, page 97. ↑

- Ibid, page 161. ↑

- Liberty County Superior Court, Deed Book I (1822-1831), page 52; digital database, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSRW-5 : 28 Oct 2024), “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” -> “Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” -> Record Book I, image #329. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L93L-P98H : 28 Oct 2024), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 149 of 689. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-PH4 : 28 Oct 2024), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 412 of 689. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, p. 53-4. Image #328-9 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSRW-5) ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, 1822-1831, p. 171. Image #287 (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSBH-18) ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-P9MC : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 288 of 689. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-P9FP : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 92 of 689; county probate courthouses, Georgia. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, 1822-1831, p. 188. Image #396 (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSBR-V) and Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, 1822-1831, p. 171-2. Image #387 (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSBH-1). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, 1822-1831, p. 172. Image #387 (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSBH-1) ↑

- James Shannon Family Bible, State Historical Society of Missouri (SHSMO), Shannon Family Papers, 1845-1960, collection # C0933; donated to the SHSMO-Columbia by Elizabeth Shannon on October 2, 1962. ↑

- Savannah Daily Republican, March 12, 1822, No 60, Vol. XX, page 1 (and others, accessed through the Georgia Historic Newspapers (gahistoricnewspapers,galileo.usg.edu) project. ↑

- Savannah Georgian, September 14, 1826, page 1. ↑

- Harrell, David E., “James Shannon: Preacher, Educator, and Fire-Eater,” Missouri Historical Review, January 1969, pp. 135-170 (https://digital.shsmo.org/digital/collection/mhr/id/32333 : accessed 9 Oct 2023). ↑

- History of the Baptist Denomination in Georgia, Atlanta, Georgia : Jas. P. Harrison & Co, 1881, p. 52. ↑

- See: History of the Baptist Denomination in Georgia, Atlanta, Georgia : Jas. P. Harrison & Co, 1881. ↑

- 1830 U.S. Census, Liberty County, Georgia, population schedule, page marked “52” in handwriting, James Shannon; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8058/images/4409522_00102 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 21 of 30. ↑

- Property Tax Digest, Richmond County, Georgia, 1829; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1729/images/40141_1220705227_0575-00052 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 53 of 105. Property Tax Digest, Richmond County, Georgia, 1827; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1729/images/40141_1220705227_0564-00071 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 165 of 245. Property Tax Digest, Richmond County, Georgia, 1828; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1729/images/40141_1220705227_0574-00055 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 132 of 182. ↑

- 1830 U.S. Census, Athena, Clarke County, Georgia, population schedule, page marked “327” in handwriting, James Shannon; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8058/images/4409522_00102 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 7 of 10. ↑

- Biographical Sketch of Dr. James P. Shannon by Scott Harp, “History of the Restoration Movement” website, https://www.therestorationmovement.com/_states/missouri/shannon.htm (accessed 28 Oct 2024). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, 1831-1838, pp. 27-8. Image #48-49 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T92T-S) ↑

- Richmond County, Georgia, Superior Court, Deed Book W, page 180, dated August 5, 1834; digital images, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-KG8T : accessed 9 Oct 2023), image 123. Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, 1831-1838, pp. 184-5. Image #133 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T921-L). ↑

- Biographical Sketch of Dr. James P. Shannon by Scott Harp, “History of the Restoration Movement” website, https://www.therestorationmovement.com/_states/missouri/shannon.htm (accessed 28 Oct 2024). ↑

- Find A Grave, memorial page for Evalina G. Dunham Shannon (d. 22 Nov 1836), Memorial # 152162234; database index with grave marker images, FindaGrave (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/152162234/evelina-g.-shannon : accessed 28 Oct 2024); citing Old Jackson Cemetery, Jackson, East Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. ↑

- Clarke County, Georgia, Marriage Records, Book B. page 308, marriage between James Shannan and Frances C. Moore, June 28, 1837; database with images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/4766/images/40660_303208-00341 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), “Georgia, U.S. Marriage Records from Select Counties, 1828-1978” -> Clarke -> Marriage Records (White and Colored), Book B, 1821-1838,” image 184 of 197. ↑

- 1840 U.S. Federal Census, Jackson, East Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, Jas. Shannon, page 3 (handwritten); database with images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8057/images/4409671_00510 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 6 of 11. ↑

- Richmond County, Georgia, Superior Court, Deed Book X, pp. 358-9, power of attorney from James Shannon to Joseph Shannon; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-KG5K : accessed 9 Oct 2023), image 514. ↑

- Richmond County, Georgia, Superior Court, Deed Book Y, p. 527, revocation of power of attorney from James Shannon to Joseph Shannon; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-N3QL-Q : accessed 9 Oct 2023), image 299. ↑

- Richmond County, Georgia, Superior Court, Deed Book Y, p. 567-8, power of attorney from James Shannon to Charles Dougherty; digital images, Ancestry.com (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-N39T-F : accessed 9 Oct 2023), image 319. ↑

- Glasgow Weekly Times, September 20, 1849, page 2. ↑

- 1850 U.S. Federal Census, Slave Schedules, District 8, Boone County, Missouri, for James Shannon, enumerated on 19 October 1850, marked 136 (handwritten); database with images, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8055/images/MOM432_422-0074 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 42 of 44. 1850 U.S. Federal Census, Population Schedule, District 8, Boone County, Missouri, for James Shannon household, enumerated 19 Sept 1850, marked 763 (handwritten); Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8054/images/4195942-00308 : accessed 28 Oct 2024), image 108 of 271. ↑

- Columbia Herald-Statesman, August 10, 1855, page 4. ↑

- St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 20, 1855, page 2. ↑

- Columbia Herald-Statesman, November 17, 1854, page 3. ↑

- Missouri State Times, July 26, 1856, page 1. ↑

- The Louisville Daily Courier, August 4, 1858, page 2. ↑

- The Louisville Daily Courier, August 30, 1858, page 2. ↑

- Find A Grave, memorial page for James Shannon (b. 23 Apr 1799, d. 23 Feb 1859), Memorial #6284079; database index with grave marker images, FindaGrave (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6284079/james-shannon : accessed 28 Oct 2024); citing Columbia Cemetery, Columbia, Boone County, Missouri. ↑

- Boone County, Missouri, Probate Court, Record of Wills, Vol. C, page 364; digital images, FamilySearch.org, “Missouri Probate Records, 1750-1998” -> Boone -> “Wills, 1850-1870, col C-D” (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9LH-33NH : accessed 9 Oct 2023), image 217. ↑

- Find A Grave, memorial page for Frances Cary Moore Shannon (b. June 1818, d. March 16, 1865)), Memorial # 6429462; database index with grave marker images, FindaGrave (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6429462/frances-cary-shannon : accessed 28 Oct 2024); citing Columbia Cemetery, Columbia, Boone County, Missouri. ↑