As the Civil War ground to an end, Liberty County, Georgia, was in disarray. It had been raided by Sherman’s Army, white families had fled their homes, and people held in slavery had been moved to other locations or left to fend for themselves. Many had scattered to follow the Army or find their own ways.

Leaders — like young Flanders Pray, a formerly enslaved man — stepped up into the chaotic post-war environment to provide the most important requirement for moving forward into a new life: education. Freed people throughout the South had an overwhelming hunger to gain the knowledge that had been denied them by law. Older people, like Windsor Stevens, sat in classrooms with children without shame. Others who had managed to gain the ability to read and write during slavery, like Flanders Pray, became their teachers.

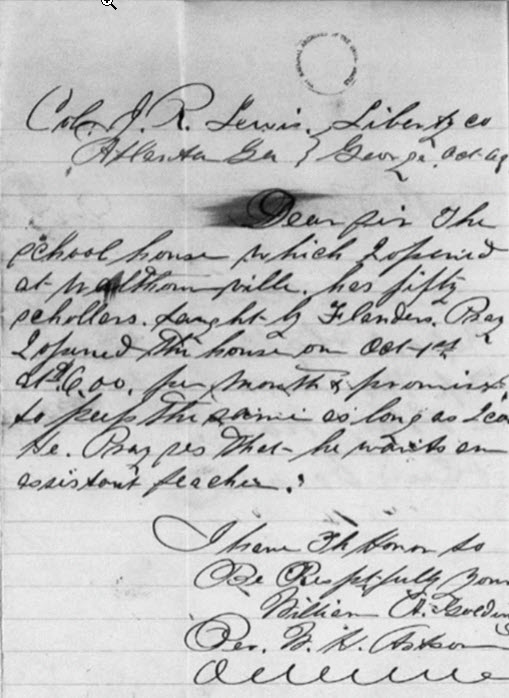

At the end of the war, Flanders Pray was being held in slavery by Charlton Hines, for whom Liberty County’s county seat, Hinesville, is named. In 1867, now a free man, he registered to vote for the first time in his life at the age of 30. Two years later, when educator and politician William A. Golding opened schools for the freedmen supported by the Freedmen’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association, he hand-picked Flanders Pray to head a school in Walthourville. Golding opened the school on October 1, 1869, with 50 pupils and reported that Mr. Pray was paid $6.00 per month and wanted an assistant teacher.

That year Flanders Pray had also been a founding member of the historic African American Baconton Missionary Baptist Church, which still exists today, and the two-room Baconton School was located on the church grounds.

The new schools faced significant backlash from the remaining white power structure within Liberty County. In November 1869, William A. Golding reported to the Freedmen’s Bureau that “a Methodist Preacher told him [Flanders Pray] that if he don’t close his school they will whip him to death that they wont be intruded on by nigras teaching.” Flanders Pray’s response? He told the man that he would support his race “as long as the breath [is] in my body and I hope the Lord will be with me.”

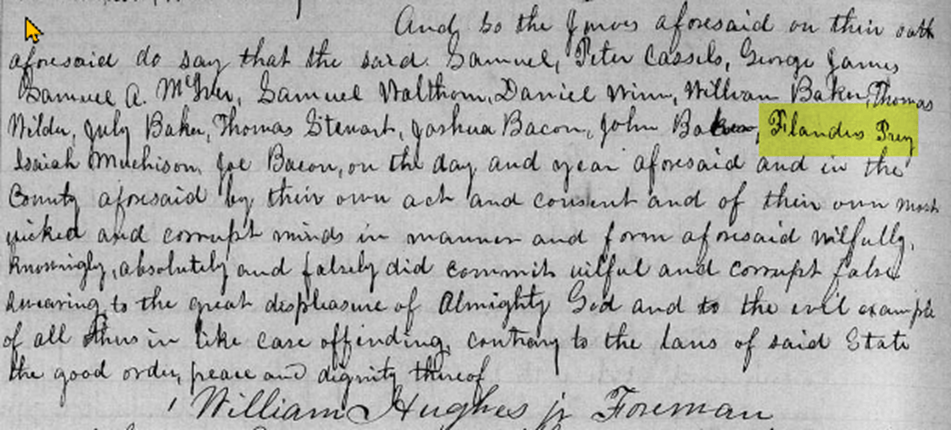

Mr. Pray’s leadership and resistance extended into the political realm. Liberty County since its founding had been a majority African American community, but that community was not able to exercise political power directly until after Emancipation. In the short period of Reconstruction, Flanders Pray was a leader in this effort. In November 1868, white court officials attempted to suppress the Black vote by refusing to open the Riceboro precinct polling place. Black leaders opened the polling place anyway and many Black voters, including Flanders Pray, voted. Their votes were not counted, and the Black voters, including Mr. Pray, were indicted by the Liberty County Grand Jury. Nothing seems to have come of the case, but the underlying threat of retribution must have been evident.

Undeterred, in 1874, Flanders Pray was appointed as the Republican Election Supervisor for Liberty County’s 16th G.M. District. Each district had both a Republican and Democrat election supervisor. He continued to act as a leader of the community after Reconstruction. In 1880, he was the elected coroner of Liberty County, serving alongside White officials who had been Confederate officers, two of whom were my ancestors.

Flanders Pray, a married schoolteacher with a young family, does not appear to have profited greatly from his leadership roles. No records were found of him owning land. In 1887, however, he was able to help his daughter, Caroline Lee, buy a Singer sewing machine on credit. To secure the loan, he mortgaged seven cows valued at $75.

He and his wife Peggy both may have died before 1910, when five of their youngest children were found in that year’s federal census living together on their own.

If Flanders Pray was “owned” by Charlton Hines at Emancipation, where did the surname Pray come from? The answer revealed his family lineage back to 1808, when one John Pray bought his grandparents, Lonnon and Cloe, and father, also named Flanders, at a public auction. They had belonged to the James B. Maxwell estate.

John Pray was a prominent land- and slave-owner of neighboring Bryan County. He saw himself as a benevolent slaveowner, and in his 1819 will he was unusually careful to describe the family relationships of the more than 120 enslaved people he named. He left Lonnon, Cloe, Flanders (Sr) and the rest of the family to his goddaughter, Mary Jane Pray Hines, wife of Lewis Hines, who was Charlton Hines’ brother.

Mary Jane Pray Hines died and the enslaved people she had inherited then belonged to her son John Pray Hines, who was a minor at the time.

Lewis Hines died in 1841, and in his estate inventory , Flanders Pray’s grandmother Chloe was said to be at Bellmont Plantation; his father Flanders, mother Flora, and her children Frank, Prince, Antonette, Jack, Flanders (Pray), Daphne, and Sampson were at the Silk Hope Plantation in Bryan County.

After an 1841 court battle with Lewis Hines’ other heirs, John Pray Hines managed to take possession of Flanders Sr, his siblings, and his mother Cloe. He promptly used them all as collateral to secure a loan he had received from the local church. If he had defaulted on the loan, they would have been sold at auction to pay his debts. Fortunately, that did not happen.

Both John Pray Hines and Charlton Hines died in 1864. Captain John Pray Hines died at the Battle of Trevilian Station in Virginia while commander of Company B, Hardwick Mounted Rifles, C.S.A. (He had been one of two delegates from Bryan County to the Georgia Secession Convention, where he voted in favor of secession.)

Charlton Hines had died a few months earlier, and John Pray Hines had been executor of his estate. Flanders Sr and his family evidently had passed into Charlton Hines’ hands at some point because they were listed and their “values” appraised in Charlton Hines’ estate.

The surviving children of Lonnon and Chloe then became free when Sherman’s Army arrived in Liberty County in December 1865.

Flanders Pray’s mother, Flora, survived to freedom and was still living on Charlton Hines’ land in 1868, when Flanders Pray’s brother John Pray opened a Freedman’s Bank account and said that his father, Flanders Sr, had died six years earlier. Another brother, Samuel Pray, was also a leader. He was the treasurer of the Poor Saints Society, also known as the Poor & Needy Society, of Skidaway Island near Savannah in 1871.

People like Flanders Pray often do not get named in the history books but their efforts on behalf of their communities to lead in every way open to them deserve to be remembered. Flanders Pray is a shining example of bravery and determination in the face of physical, emotional and intellectual oppression, intimidation and discrimination.

Want to learn more about Flanders Pray? You can find a much more detailed account of his life (with footnotes!) at the They Had Names website. You’ll also find a transcribed copy of John Pray’s 1819 will and the other documents mentioned in this account.

In January 2025, Flanders Pray was posthumously awarded the Liberty County Martin Luther King Jr. Observance Association “Lifetime Achievement Award” in the presence of many of his local descendants.