These “research snippets” are correlations found while documenting references to named African Americans in Liberty County, Georgia, probate, court, and church records. This is analysis and not confirmed. Please refer to the original documents referenced below to compare these speculations with your own research.

Liberty County documents and a complicated web of white planter family relationships revealed the family history of Silla, an enslaved woman, and her children Amy, Champion (“Champ”), Rose, Cate, Dinah, and Betty.

In 1769, in St. Johns Parish in what was then colonial British Georgia (now Liberty County), Audley Maxwell wrote his will[1]. He named his son James Maxwell and his sons-in-law John Sandiford and Andrew Elton Wells, his wife Hannah, and his grandchildren Audley Maxwell, son of his deceased son Audley Maxwell Jr, and his granddaughter Elizabeth Maxwell. John Sandiford was married to Maxwell’s daughter Mary Esther, and Andrew Elton Wells was married to Maxwell’s daughter Jane[2].

In this will[3], Audley Maxwell left to John Sandiford, presumably as the representative of his wife, Maxwell’s daughter Mary Esther, “one half of a Tract of Land Situated on Newport Adjoining Lands of John Mitchell Mathew Smallwood and John Davise also one Negro girl named Beck also Eleven Cows and Calves, the said wench and Cattle being deliver’d [sic] to him and his Heirs forever.”

John Sandiford died in 1784, and Mary Esther (Maxwell) Sandiford then married Joseph Law. On November 30, 1803, she wrote her will[4]. She left Beck to her daughter Elizabeth, John Sandiford’s daughter, who had married James Wood. The will also identified a family of enslaved people: Sillah and her eldest daughter Amy, her eldest son Champion, her daughters Rose, Cate, Dinah, and her youngest child Betty[5].

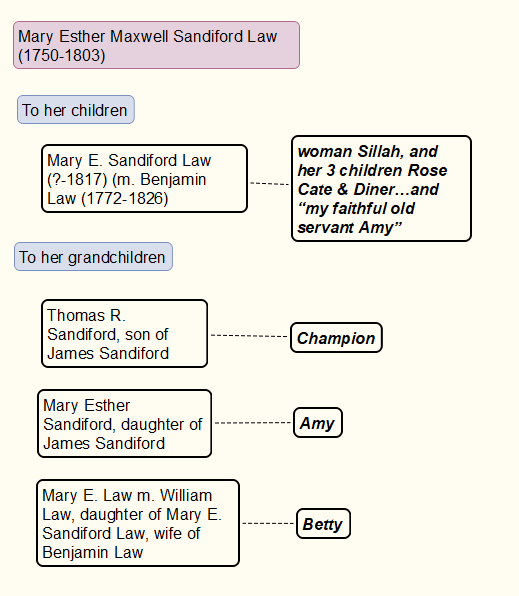

Mary Esther (Maxwell Sandiford) Law divided this family in her will as follows:

Sillah ($500) -> daughter Mary Law

Amy (eldest daughter) ($380) -> Mary E. Sandiford

Champion (eldest son) ($470) -> Thomas R. Sandiford

Rose ($250) -> daughter Mary Law

Cate ($200) -> daughter Mary Law

Diner/Dinah ($100) -> daughter Mary Law

Betty ($60) (youngest child) -> granddaughter Mary E. Law

Old Amy -> daughter Mary E. Law

Nimrod -> grandson John Sandiford

Moses -> son James Sandiford

Beck -> daughter Elizabeth Wood

Following is a visual depiction of the division of Sillah’s family’s division:

Fig. 1 Division of Silla’s Family, 1803

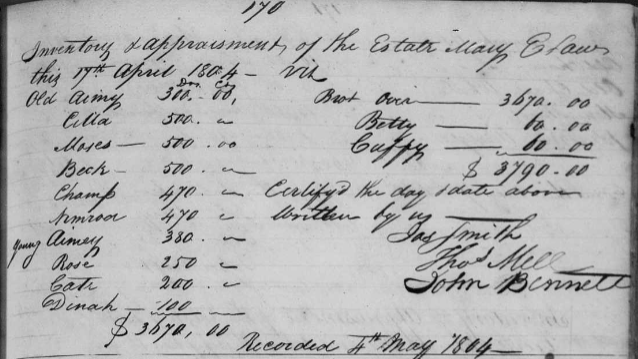

On April 17, 1804, Mary E. Law’s estate was inventoried and appraised[6].

Fig. 2. Inventory of Mary E. Law’s estate, 1804

The fact that Silla (Cilla) named her daughter Amy (Aimey) suggests that perhaps Old Amy (Aimy) was a relative of hers, possibly even her mother, but no proof of this was found during this study. Also, Cuffy was not named in Mary E. Law’s will. That and the low value placed on him (equal to the value placed on Silla’s youngest daughter, Betty) suggest that he might have been born between November 30, 1803 (Mary Law’s will) and April 17, 1804 (the estate inventory), and that he could have been Silla’s son.

Silla’s family was now divided. However, although no documents were found naming them again until 1827-1828, those documents revealed that the family appeared to have been reunited, now owned by Mary E. Law’s son-in-law Benjamin Law, who was married to her daughter Mary Sandiford, who had inherited Willa, Rose, Cate, Dinah, and Old Amy. Unless legally documented otherwise, normally at that time a woman’s property became her husband’s property upon their marriage.

On January 30, 1827, Benjamin Law, still living in Liberty County, used as collateral on a set of promissory notes “the following negro slaves, viz. Balaam, Cubit [alt: Cupid?], Boston, April, July, Rose, Kate, Dinah, Sylvia, Sam, Bess, Silla, Champ, Sambo, Amy, Cadmus, Monday, Bess, Nat, Dinah, Silla, Bob, Sally, Frank, Sabine, Beck, together with the future issue & increase of the said female slaves.” Nathaniel Law and William Law, Benjamin’s son, had acted as security for promissory notes by Benjamin Law, and he used these enslaved people as collateral to ensure them against loss.

Thus it appeared that Champ and Amy had joined their siblings under the ownership of Benjamin Law and Mary E. Law. Or had they? It is definitely possible that there was a deed of conveyance that was not recorded in court from Mary Esther Sandiford and Thomas R. Sandiford, the children of James Sandiford who had inherited Amy and Champ, respectively, from Mary E. Law. Such deeds might be written between family members but not recorded in court until, or unless, needed.

It is also possible, however, that this Champ and Amy are not the same people as in the Mary E. Law will and estate inventory. They could conceivably have been Silla’s grandchildren who had received their aunt’s and uncle’s names. One way to determine this would be to look for estate inventories for Mary Esther Sandiford or Thomas R. Sandiford to see if Champ or Amy were named.

In 1815, James Sandiford “delivered up to Andrew F. Fraser…my son Thomas Rivers Sandiford, and given said Fraser full power to bind said Thomas to a trade, or bring him up in any moral occupation, he thinks proper,” until he became 21[7]. By 1830, Thomas R. Sandiford appeared to have moved to Twiggs County. No estate inventory was found in a quick search, but more research would need to be done. If the 1830 census[8] was indeed referring to this Thomas R. Sandiford, that man owned two male slaves under two years old, two female slaves under 10, and 1 female slave between 24-35, so it would appear that the man named Champ who was named in Mary E. Law’s 1803 will was not there, which might be an indicator that Champ had been left in Liberty County and thus the Champ in Benjamin Law’s possession was Silla’s son Champ. More research needs to be done to establish whether this is likely.

It was not possible to research Mary Esther Sandiford, the daughter of James Sandiford who inherited Amy, within the scope of this study.

Benjamin Law, who had used Silla’s family as collateral in early 1827, died on March 12, 1827[9]. The February 1828 estate inventory and appraisement[10] listed, among others:

| Name | Appraised Value | Comments |

| Rose | $400 | “Rose + infant” |

| Kate | $350 | |

| Champ | $300 | |

| Amy | $200 | |

| Dinah | $200 | |

| Silla | $150 |

On April 1, 1828, following foreclosure of what appears to be the 1827 mortgage to Nathaniel Law and William Law, all the people named in Benjamin Law’s estate inventory, including Silla’s family, were sold at a Sheriff’s Auction to William Law, Benjamin Law’s son[11].

William Law was born in Sunbury, Liberty County, in 1793, but moved to Savannah around 1812, where he was a prominent lawyer. He also represented Chatham County in the state legislature in 1823-5. He died after the Civil War (1874) so no estate inventory was found that could have named members of Silla’s family who were still living, but he did use them and the others as collateral on a mortgage the day after he purchased them at the Sheriff’s Sale[12].

The last mention found of members of Silla’s family in Liberty County records was in this 1828 chattel mortgage. No records relating to them were found by searching Chatham County deed records related to William Law but that does not mean that records do not exist somewhere.

Silla was of course of childbearing age in 1804 when she was listed in Mary E. Law’s estate inventory, and all of her children discussed in this study were born by then. It is unlikely that Silla lived to Emancipation. Her youngest child, Betty, if only 1 year old in 1804, would have been 67 by the time of the 1870 census. Thus it seems it would be unlikely to find any of the family in the 1870 census, and even if they were there, the women would be difficult to identify, since they had relatively common names.

However, Champion (“Champ”) was not a common name. In a search of the TheyHadNames database, which now has all the references to African Americans found in Liberty County wills, estate inventories, and deed records from 1777-1865, only a few other references to a man or boy named Champ were found:

-a Shampain/Champain in Roger Park Saunders chattel mortgage in 1789[13] and in his 1790s estate inventory[14]

-a Champaign in John Hext’s 1790s estate inventory[15]

-A man named Champaigne in Samuel Proctor Bayley’s estate inventory in 1803[16]

-Champaign (age unknown) in a chattel mortgage by Roger Sanders Gough in 1804[17]

-Champ in William West’s estate inventory in 1802[18]

None of the people listed above were likely to have survived to the 1870 census, or would have been very aged if they had. Only one man named Champion or Champ was found in the 1870 Liberty County census. He was Champion (“Champ”) Blake, born around 1820[19]. Even accounting for the variations in birth dates given by the census records, it is unlikely that he was the Champ named in any of the above records. However, names do get passed down through time, and it is possible that he had a family connection with one of them.

Endnotes

- Wills, Colony of Georgia, RG 49-1-2, Georgia Archives”, Colonial Estate Records, held by Georgia Archives Virtual Vault; accessed online at: https://vault.georgiaarchives.org/digital/collection/cw/id/1177/rec/166. ↑

- Andrew Elton Wells will named as executors his brothers-in-law John Sandiford and James Maxwell, and identified his wife as Jane. “Wills, 1775-1927; Author: Georgia. Court of Ordinary (Chatham County); Probate Place: Chatham, Georgia,” in Georgia, Wills and Probate Records, 1742-1992, an Ancestry.com collection. Accessed on 5/27/2022 at https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8635/images/005759790_00330. ↑

- See the will for other bequests naming enslaved people. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L93L-P9CR?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 83 of 689. ↑

- The relationships mentioned were named in the will. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-PGT?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 266 of 689. ↑

- A number of Ancestry.com family trees show James Sandiford as having died in 1810, but no documentation was found. This deed record appears to indicate that he was still alive in 1815. See Liberty County Superior Court, “Deeds & Mortgages v. H 1816-1822,” p. 95; digital image, FamilySearch.org, “Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831” within “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” image #77, (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSYJ-J?i=76&cat=292358, accessed 5/27/2022). ↑

- 1830 U.S. Census, Twiggs County, Georgia, population schedule, p. 85, Thomas R. Sandefor; digital image, Ancestry.com, image #51 (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed 5/27/2022). ↑

- Ancestry.com, digital image from “Savannah, Georgia Vital Records, 1803-1966.” P. 301, image #6. (Accessed 5/27/2022, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/166379:2209?ssrc=pt&tid=160855012&pid=362125198974.) ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L93L-GCXP?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 461 of 689. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, 1822-1831, p. 379-80. Image #497-8 (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSYS-3?i=496&cat=292358). ↑

- Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book I, 1822-1831, p. 310. Image #463 (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSY1-M?i=462&cat=292358). ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. A-B 1777-1793,” Record Book B, 1787-1793, p. 395-9. Image #478-480 (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSLZ-FPB5?i=477) ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-893L-P9SX?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 223 of 689 ↑

- ”Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-P931?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 221 of 689 ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L93L-PVF?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 257 of 689. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. E-G 1801-1816,” Record Book E (1801-1804), p. 186-8. Image #104 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QL-J969-2?i=102&cat=292358) ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-893L-PY2?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 243 of 689. ↑

- Be aware when searching the 1870 census for Liberty County on Ancestry.com or FamilySearch.org that they both include a fraudulent census conducted by Charles Holcombe. This census was rejected, and another 1870 census was conducted that fall by local planters. The fraudulent Holcombe census did list two people named Champ, but these names are likely to have been completely made up, in the author’s experience. Look for the name Holcombe as the enumerator to identify this fraudulent census. ↑