I’ve posted previously about a church record and an estate inventory I found in a book that were created by combining parts of historical documents from Liberty County, Georgia. These illustrate the need to verify any document you plan to use in your family history research. It may be easier now than it ever has been to create fraudulent documents to “prove” a family line, but it’s always been possible to do and there have always been people who will do it. It’s very important to check your sources always so that you don’t innocently perpetuate someone else’s mistake or even fraud.

Again, I have not named the book because I’ve tried several times unsuccessfully to reach the author and don’t want to implicate someone who may have unknowingly received falsified images through another researcher.

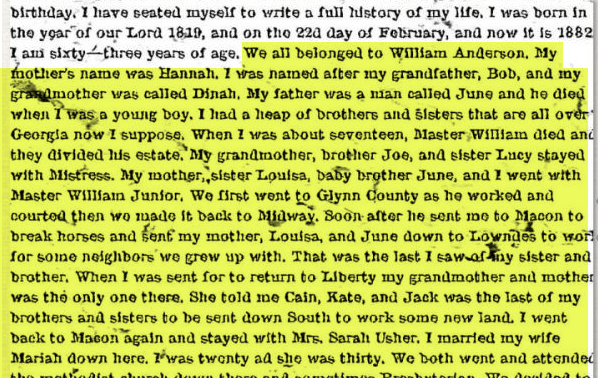

Another image from that book illustrates the same point but in a slightly different way. Here’s the image, which is a page from the published autobiography of Reverend Robert Anderson, a formerly enslaved man originally from Liberty County, Georgia. The autobiography is a remarkable historical document, but — in this version — also apparently a genealogy treasure. Look at all the detail in the highlighted section.

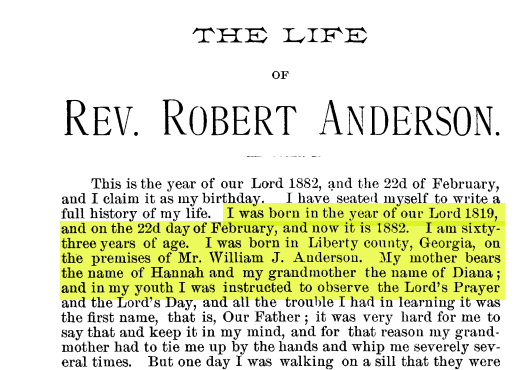

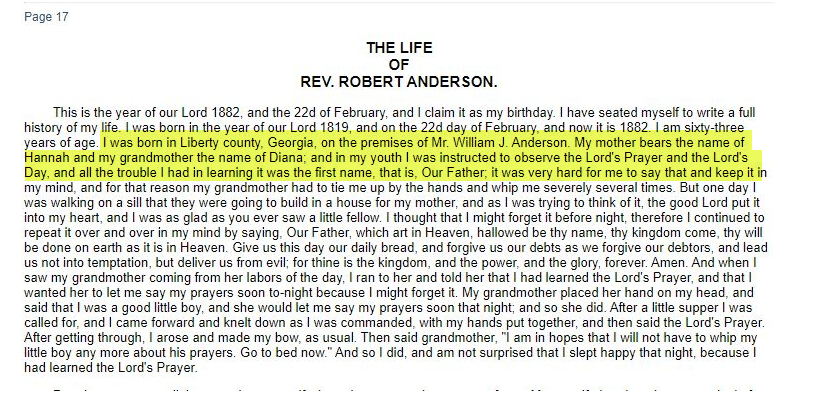

The problem? When I checked two copies of the original that are online at reputable sources, they don’t include the above highlighted portion. See them below, with links.

The “added” highlighted portion appears designed to support a particular family line narrative in the same way that the altered estate inventory and church record were.

Download this OCR version of the original at Emory University’s website. Do read it — it’s a remarkable book!

See this transcription of the original memoir at the wonderful Documenting the American South website.

This example is different from the church record and estate inventory examples, because I can’t be certain that these two other sources didn’t for some reason omit the detailed genealogical portion. The original is held at the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries and would have to be checked there. It seems unlikely that both Emory University and the Documenting the South website would have left that portion out.

This again highlights the need to verify, verify, verify.

I wouldn’t normally have thought to check an image of a published item had it not been for the other two problematic Liberty County images in that book…and because I remember being disappointed when I originally read Reverend Anderson’s autobiography online and noticed the lack of genealogical detail for his Liberty County family.

There are reasons we do genealogy. One of them is to ensure that the ancestors are remembered, especially those for whom there may be few records, like people who were held in slavery. As a descendant of enslavers, I feel a particular responsibility for this, but all of us should do our best not to pass along mistaken research or fraudulent documents. The best way to do that is to research thoroughly every piece of evidence you find, no matter how beautifully presented or seemingly original. We need to check the original sources, whether at the repository or a digitized version at a reputable online source like Ancestry or FamilySearch, and always cite our sources.