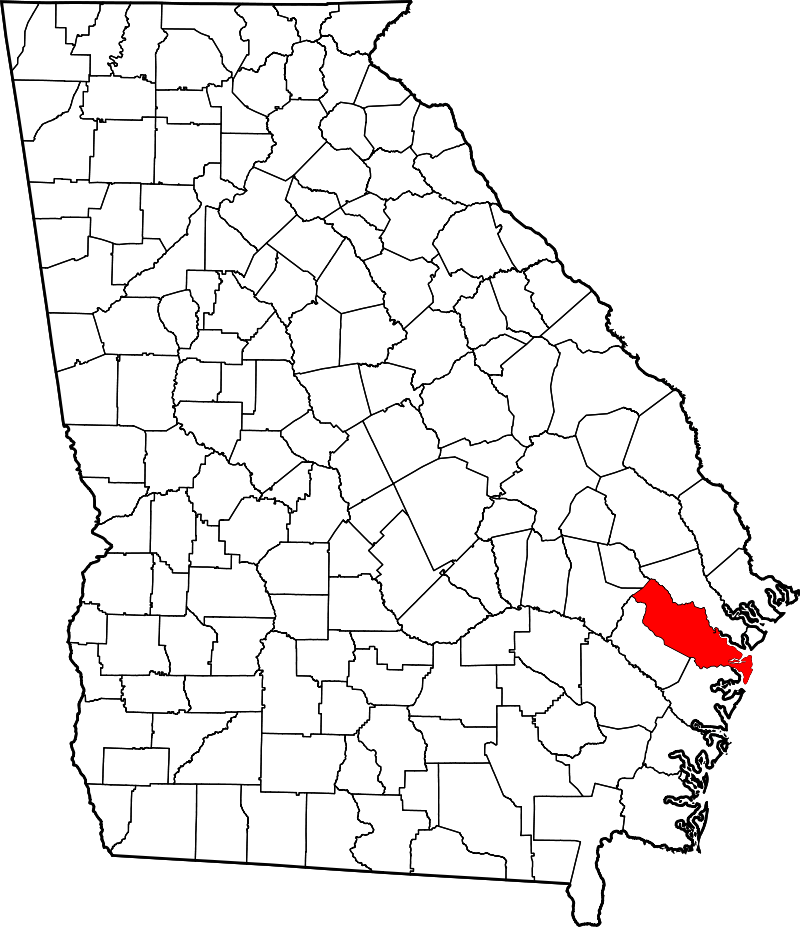

James and John Somersall were white brothers who lived in rice-growing, slave-owning Liberty County, Georgia. They were poor. They owned a few acres of land, grew their own food, milked their own cows, and didn’t own people.

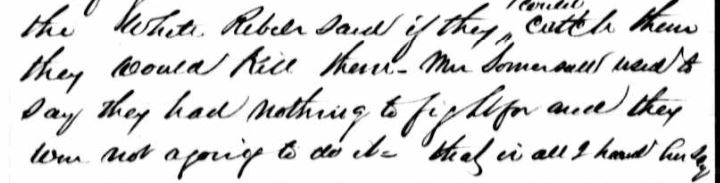

John was in his late 30’s when the clouds of the Civil War appeared on the horizon, and his view of the matter was that he had nothing to fight for. His mother, Elizabeth, a widow, tried telling her neighbors that they shouldn’t fight to keep their slaves. She told them that if she did own slaves, even a lot of them, she would gladly give them up to keep the war away. John had to tell her to stop, that they were going to come for her and kill him for defending her. She stopped.

John didn’t seem to think there were states’ rights involved. He thought he was poor, and that he was going to get killed so that rich men could keep on profiting from owning people.

How do we know that? As the war was starting, he went to the nearby Laurelview plantation, owned by the wealthy Jones family, and found Sam, an enslaved man he knew.

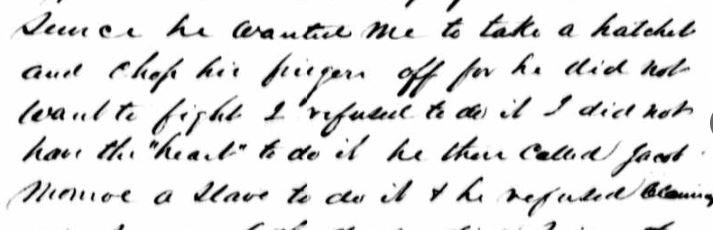

He said he knew the South was going to lose, and asked Sam to take a hatchet and cut some of his fingers off.

So he wouldn’t have to fight.

Sam wouldn’t do it. John asked Jacob, another enslaved man. He also refused.

John and James were forced to join up. James was in the Liberty Independent Troop, 5th Georgia Cavalry. At the end of October, 1864, as Sherman’s Army prepared to march for Savannah, he was sick in a Savannah hospital. He and John then deserted and hid in the woods near their mother’s house in Sunbury, Liberty County.

Moke, an enslaved man who lived about two miles from them and belonged to William Thompson, used to bring them food. Their mother Elizabeth told Moke, “They have nothing to fight for and they’re not going to do it.”

The rebels were looking for John and James, suspecting they had gone to their mother’s, and Moke had heard they would be killed if caught. Elizabeth wanted Moke to hide James, who was probably still too ill to be hiding out in the woods, but Moke was afraid, because he had known some slaves “whipped nearly to death for harboring a deserter & that was as bad, as shooting would not hurt so bad.”

Lafayette, another enslaved man at Laurelview Plantation, recalled that James and John were hunted by the rebels with dogs while they were hiding, adding, “They were poor men. They owned nothing but horses & cows & such things. They could not go in a rich man’s home in Liberty County.”

The U.S. Army showed up in Liberty County before James and John were caught by the rebels, and they and their mother lost everything. The U.S. soldiers stripped their property of everything that could be eaten, fed to horses, or burned for cooking fuel and to keep warm, as they did to the rest of Liberty County, both white and black.

Sam, the enslaved man who wouldn’t chop James’ fingers off, took the surname Elliott and successfully sued the U.S. Government in the 1870s under the Southern Claims Commission program to get paid back for the property the soldiers took from him.

Lafayette took the surname DeLegal, and also successfully sued the U.S. government for compensation.

John and James both died a few years after the war. Elizabeth Somersall tried suing for compensation for all that she lost when the U.S. soldiers came through Liberty County, but was refused. To get compensation, claimants had to prove that they had been against the rebellion. Only Elizabeth’s African-American neighbors would testify that she was against the war. Ironically, the Southern Claims Commission officers felt that she should have been able to find white neighbors who would testify that she had supported the U.S. cause.

Sam Elliott, Moke Todd, and Lafayette DeLegal did testify for her. They were farmers in Liberty County after the war. Sam walked 15 miles each way to testify for her, even though it was August and the weeds were growing fast in his corn and rice fields. He said he came “out of kindness” and that he was “glad to help the old lady if I can.” Lafayette said in his testimony, “If I should go to her house now she would set me at her table just the same as herself.”

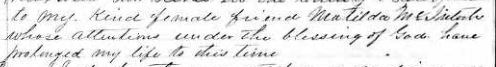

Elizabeth died in October 1877 at 84. She gave her house and the surrounding lot in Sunbury to a much younger sea captain who lived with her, and gave a 10-acre plot of land her son had bought from William King to “my kind female friend Matilda McIntosh whose attentions under the blessing of God have prolonged my life to this time.” Matilda was a 62-year-old African-American widow who was born enslaved in Savannah. She had been owned by George W. Walthour, of Walthourville, Liberty County, until the war set her free.