By Stacy Ashmore Cole (5/16/2022)

Edited on 5/18/2022: Changed the paragraph on manumissions to show that it was still possible to manumit enslaved people by application to the Legislature (thanks to Elizabeth Olson).

An interracial marriage recorded in 1818 in Liberty County, Georgia, helps illustrate the social environment of the time. This and other records demonstrate white planters and slaveowners attempting to provide for their mixed-race children, while denying the humanity of the people they were holding in slavery.

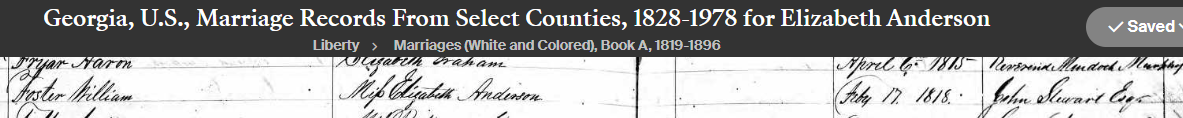

On February 17, 1818, William Anderson, a planter and slaveowner of Liberty County, Georgia, watched John Stewart conduct the marriage[1] of Miss Elizabeth Anderson, a young woman of color, and William Foster, also a Liberty County planter and slaveowner.

Fig 1. Marriage record for William Foster and Elizabeth Anderson, 1818

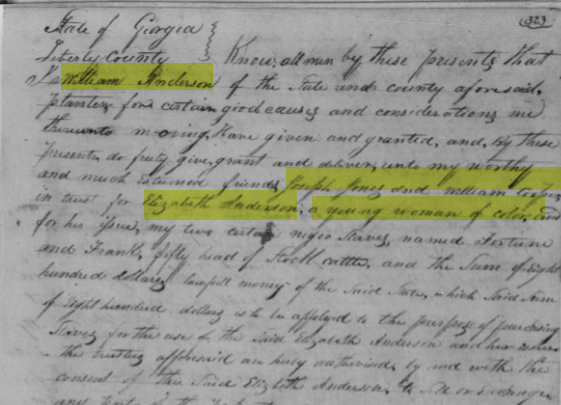

On that day, William Anderson established a trust for Elizabeth Anderson[2]. He named his friends Joseph Jones and William Cooper, both also Liberty County planters and slaveowners, as her trustees, and gave them, to keep in trust for her, two enslaved men named Fortune and Frank, fifty head of cattle, and $800 that they were to use to purchase additional slaves for her. William Anderson identified Elizabeth Anderson only as “a young woman of color.”

Fig 2 1818 William Anderson gift to Elizabeth Anderson

This marriage between “a young woman of color” and a white, wealthy Liberty County planter and slaveowner would presumably have been shocking for its time. What was its purpose? It seems likely from all the documentation that Elizabeth was William’s daughter or some other relationship, and that this was an attempt to provide for her. Why was it necessary? And why not free her?[3]

Georgia had been working on prohibiting manumissions for some time[4]. An act of 1801 outlawed manumission unless approved by the Legislature. In 1815, it was made illegal for probate court judges to record any deed of manumission, and in 1818, stricter rules were put on manumission, although it could still be done by application to the Legislature, and any slave who was manumitted could be seized and sold at auction. Free persons of color were to be required to register and were forbidden to own real estate or slaves.

This law was about to take effect, and Elizabeth Anderson would be vulnerable to anyone who decided it should be enforced. William Anderson was 41 at that time; he was married and his first daughter with his wife, Sarah A. Anderson, was to be born that year. He was holding 25 people in slavery, and he was a member of the Midway Congregational Church. He did not seem to be in a good position to protect Elizabeth personally, assuming that was his wish; his desire could also have been to remove her from his life, with his wife about to have their first child. He could not legally free her without applying to the Legislature, and since she apparently was not free[5], she could not have a guardian named, as was about to be required by law for free people of color. Even if she were free, she could not legally own property.

Marriage to a white man was an unusual solution – no other such case has been found in Liberty County records so far – but it did resolve some of the problems, because her husband would be considered responsible for her, and the marriage settlement named two prominent white trustees who could hold property for her.

Was it not illegal for a white man to marry a Black woman at that time? Although an exact timeline of Georgia’s early anti-miscegenation laws has proven difficult to find, it seems likely. However, laws on the books are not always enforced, and she had powerful protectors in her trustees, Joseph Jones and William Cooper, both wealthy white planters and slaveholders.

The cultural environment of Liberty County in that time may also have assisted her. Although Liberty County planters and slaveholders certainly believed in the institution of slavery and held strong views about the racial inferiority of African Americans, these prejudices seemed in some cases not to extend to their own children by enslaved women.

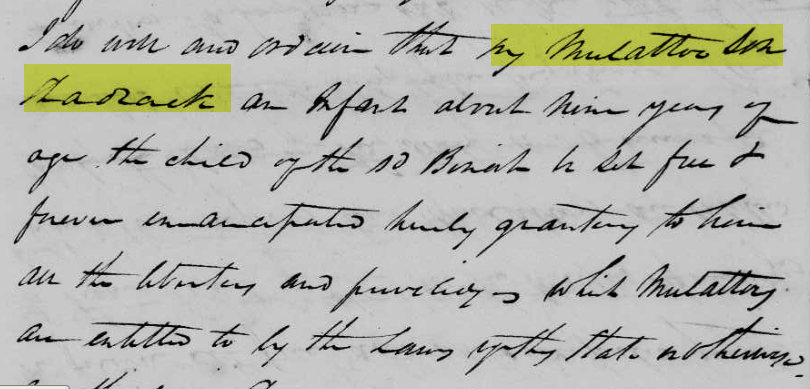

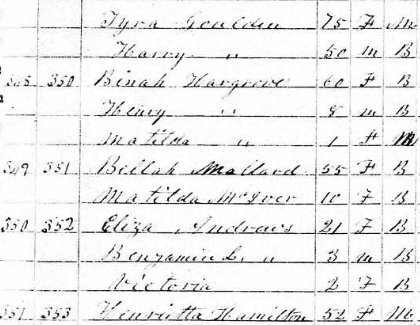

In 1828, William Foster’s and William Anderson’s neighbor, Joseph Hargreaves, a wealthy white planter and slaveowner died, attempted via his will to leave ¼ of his estate to Shadrach, whom he acknowledged as his mixed-race son by his enslaved woman Binah[6]. He also named two local white planters as Shadrach’s trustees. Although his will was altered before being probated because parts of it referring to Shadrach were illegal, and Shadrach did not in fact inherit, the white planters did send Shadrach to England to Hargreaves’ nephew, where he lived life as a free man. Shadrach’s mother Binah lived afterward as a free woman of color in Liberty County, legally or not.

Fig 3 Joseph Hargreaves will naming Shadrach as his son

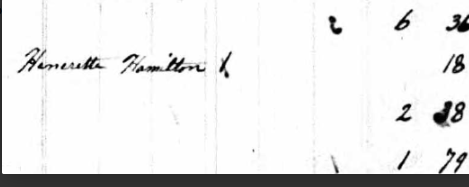

Henrietta Hamilton[7], a free woman of color about the same age as Elizabeth Anderson, was listed by name in the 1830 U.S. federal census in Liberty County. She was protected by wealthy white planters throughout the rest of her life, and in fact owned enslaved people (who of course may have been family members).

Fig 4 Henrietta Hamilton, free woman of color, named in 1830 census

Other free women of color who seem likely to have been the children of white planters have been documented living in a cluster in Liberty County in the 1850s[8].

Fig 5 Free women of color cluster in 1850 Liberty County census

William Foster, the man who married Elizabeth, was from a family that had been among the earliest European-descended settlers in that area of Georgia. His father, John Foster, signed the articles of incorporation of the Midway Church in 1754[9]. He had married another member of the “founding” families, Lydia Way. At his death in 1790, John Foster had five enslaved people in his estate inventory[10].

Perhaps William Anderson hoped and expected that the complex web of protection he had spun over Elizabeth would be enough to keep her safe.

Whatever his motives, it appears to have worked.

By 1820[11], when Elizabeth Anderson was represented in William Foster’s household by the census as a free woman of color aged 14-25 (she was 21), William Foster was holding 25 people in slavery. William and Elizabeth’s first daughter, Susannah M. Foster, born November 21, 1818, was listed in the household as a free female of color under 14 years of age.

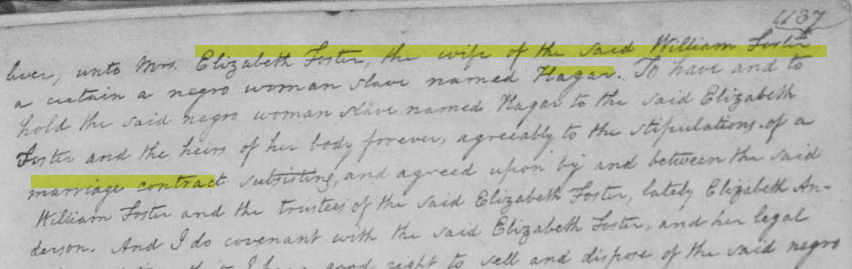

William Anderson’s wishes that the $800 he gifted to Elizabeth on her marriage be used to purchase more enslaved people for her were carried out. On March 31, 1818, Benjamin Mell, a Liberty County planter, sold to Mrs. Elizabeth Foster, wife of William Foster, for $700 “a certain negro slave named Hagar.” Mell noted that this was per the stipulations of the marriage contract between William and Elizabeth Foster, who had been Elizabeth Anderson before her marriage.[12]

Fig 6 Sale of Hagar to Elizabeth Foster

Hagar may have been previously owned by Thomas Mell Senior, as a Hagar was seized from Thomas Mell Senior and sold at a Sheriff’s Sale on July 5, 1814, to Benjamin Mell for $220[13]. No one named Hagar was listed in Jonathan Bacon’s 1843 estate inventory.[14]

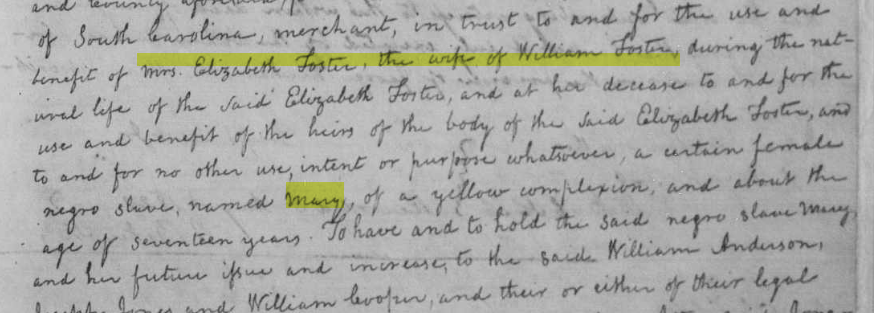

On March 8, 1819[15], Jonathan Bacon sold to William Anderson and Joseph Jones, identified as Liberty County planters, and to William Cooper, identified as a merchant of South Carolina, “a certain female negro slave, named Mary, of a yellow complexion and about the age of seventeen years,” in trust for Mrs. Elizabeth Foster, wife of William Foster. Jonathan Bacon was married to William Foster’s sister Mary.

Fig 7 Sale of Mary to Elizabeth Foster

William Anderson died sometime before his estate inventory was conducted in May 1825[16]. It showed that he had owned 57 enslaved people in at least two locations with a total appraised value of $14,155. He died without a will, and Elizabeth does not appear to have received anything from his estate, unless it was done informally. His estate was divided in 1835[17], 1837[18], and 1841[19] as his children came of age. The heirs were his widow, Mrs. Mary E. Anderson, and her children Joseph A. Anderson, Sarah Anderson, Marion Anderson, William J. Anderson, and David Anderson.

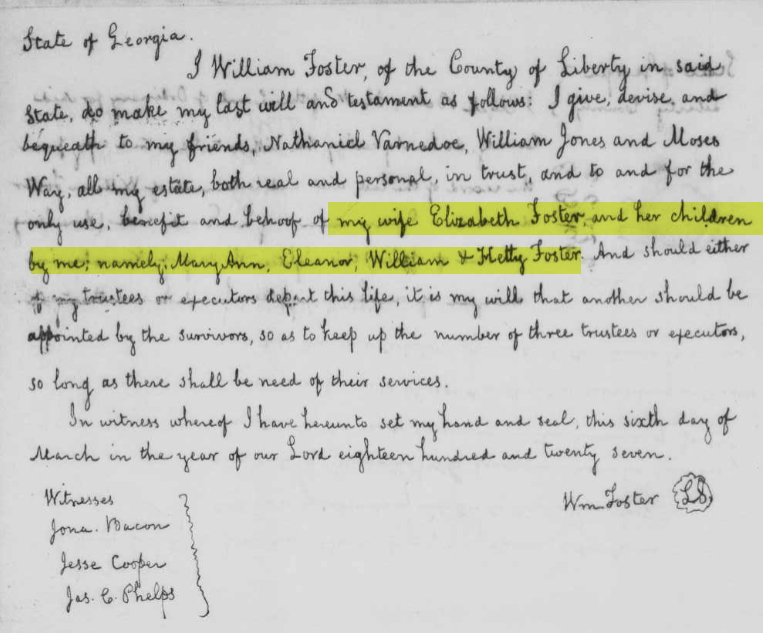

Elizabeth’s husband William Foster died in 1827, sometime after March 6th, when he wrote his will[20] leaving everything to Elizabeth and to his four children, whom he specifically identified as his: MaryAnn, Eleanor, William and Hetty. He named as trustees for them his friends Nathaniel Varnedoe, William Jones, and Moses Way, all prominent and well-off Liberty County planters and slaveholders. Moses Way was likely the father of William Foster’s mother Lydia. Jonathan Bacon, Jesse Cooper, and James C. Phelps witnessed the signing of the will, and Jonathan Bacon probated it in court before three Inferior Court Judges on January 7, 1828.

Fig. 8 William Foster’s 1827 will

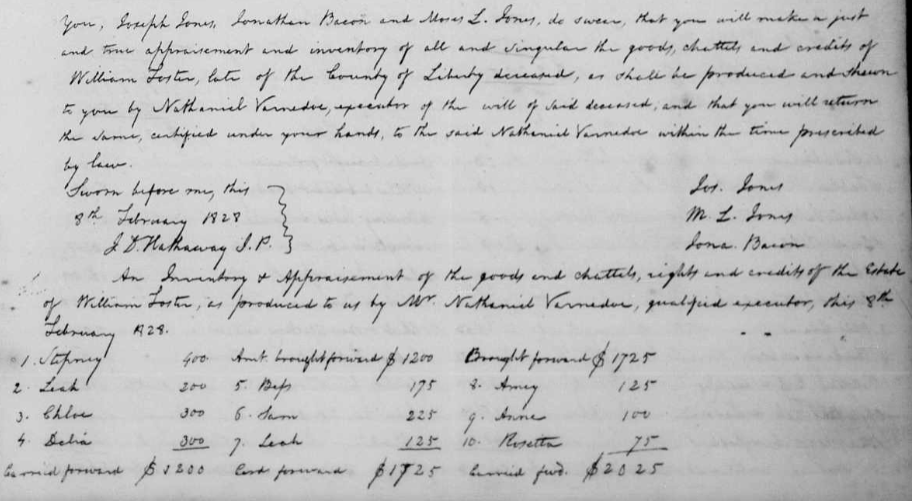

The estate inventory performed in February 1828[21] showed that Foster had 10 enslaved people, appraised at a total value of $2025.

Fig 9 William Foster estate inventory

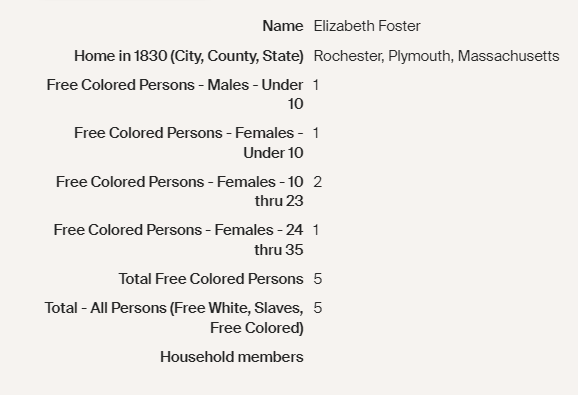

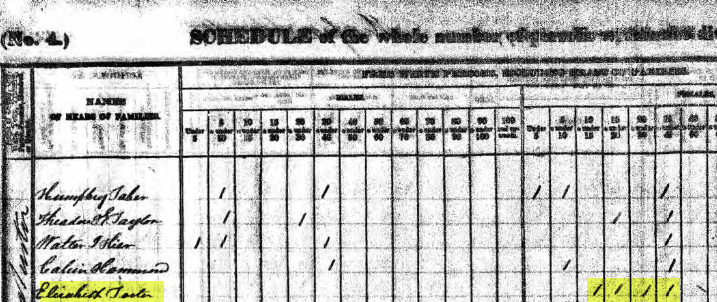

It is not hard to imagine Elizabeth (Anderson) Foster’s feelings and fears upon her husband’s death, and indeed, she took her four children and moved to Massachusetts. The first time she appeared in the U.S. census under her own name was in Rochester, Plymouth County, Massachusetts in 1830[22]. Her household was comprised of a free woman of color between the ages of 24 to 36 (herself), 2 free females of color between 10-24, 1 free female of color under the age of 10, and 1 free male of color under the age of 10.

Fig 10 Elizabeth Foster in the 1830 census

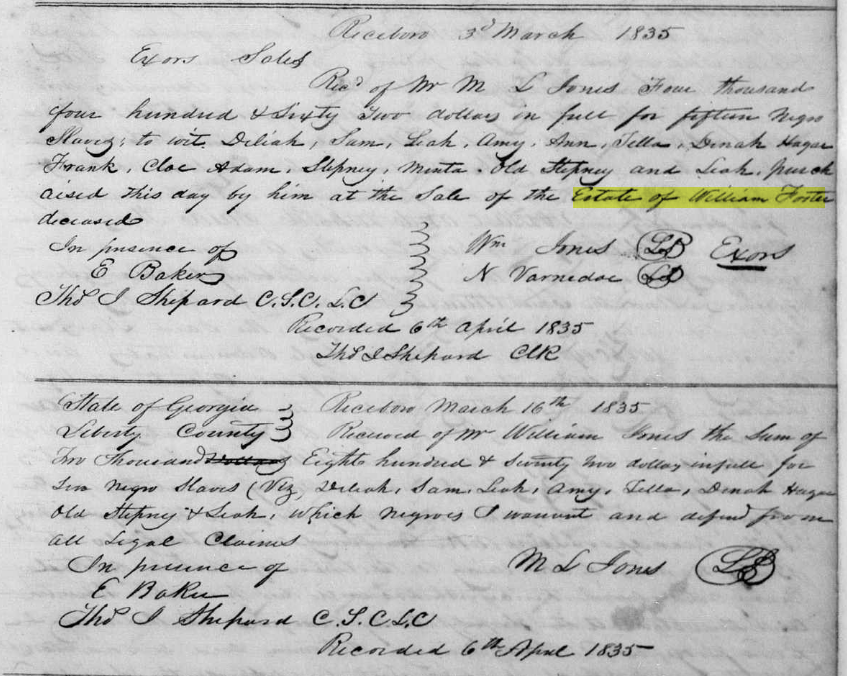

Moses Way, one of the executors of William Foster’s will, passed away shortly thereafter, but Nathaniel Varnedoe and William Jones continued to maintain the estate, submitting annual reports until 1835, when they obtained court permission to sell the estate. On March 3, 1835[23], in Riceboro, Liberty County’s seat, they sold to M.L. Jones for $4462 “fifteen negro Slaves: to wit, Deliah, Sam, Leah, Amy, Ann, Tilla, Dinah, Hagar, Frank, Cloe [alt: Chloe], Adam, Stepney, Minta [alt: Minder], Old Stepney and Leah.”[24] On March 16, M.L. Jones sold ten of these people — Deliah, Sam, Leah, Amy, Tilla, Dinah, Hagar, Old Stepny and Leah – to his brother, William Jones, the executor[25].

Fig 11 Sale of enslaved people belonging to estate of William Foster

The executors also sold William Foster’s land to Peter W. Fleming for $305, describing it as 200 acres bounded on the north by the Hargreaves estate, south by land of Jonathan Bacon, east by land of Jesse Cooper, and west by land belonging to the Anderson estate. So it was William Foster’s neighbors who witnessed the signing of his will, and his land neighbored that of William Anderson.

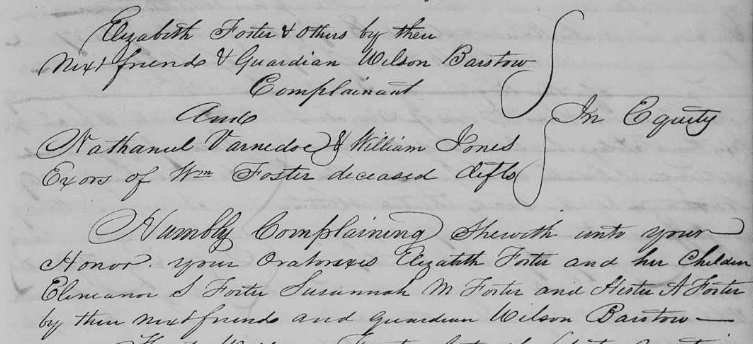

What happened to the proceeds from the sale? In 1835, Elizabeth Foster, living in Rochester, Massachusetts, sued Nathaniel Varnedoe and William Jones in Liberty County Superior Court[26]. Her attorney, William Barstow of Rochester, Masschusetts, who was also the legal guardian of her minor children, acknowledged that Mrs. Foster had agreed to the sale of the estate, but stated that the executors had refused to convey the proceeds to her in Massachusetts through her attorney. Exhibited as evidence were William Foster’s will, legally probated; documentation of Barstow’s appointment as the Foster children’s guardian; and Elizabeth Foster’s power of attorney given to Barstow to collect the estate’s proceeds.

Fig 12 Lawsuit by Elizabeth Anderson against executors of William Foster’s estate

The defendants acknowledged that Foster’s will was legal but said they had been advised that they could not safely turn over the proceeds of the sale without the court’s permission. They stated that they had decided to obtain permission to sell the estate because it had become “difficult & troublesome” to manage it, and that they had obtained $5429 from the sale.

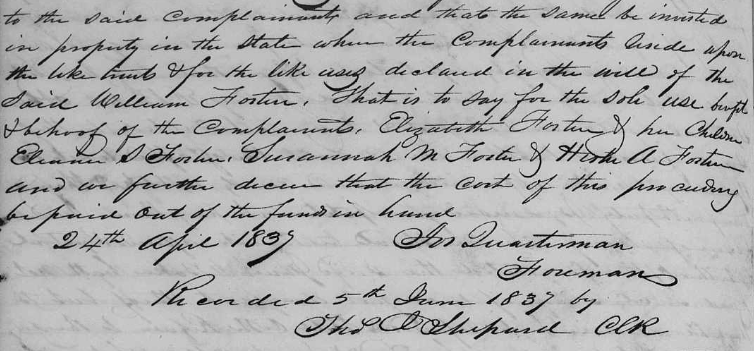

The Liberty County Superior Court jury, headed by Joseph Quarterman, ruled in favor of Mrs. Foster on April 24, 1837, ordering that the money should be handed over to William Barstow by the defendants and invested in the state where Mrs. Foster resided for the purpose described in William Foster’s will, i.e., the “sole use, benefit & behoof of the complainants, Elizabeth Foster & her children.”

Fig 13 Jury verdict in Elizabeth Anderson’s lawsuit against executors

In the lawsuit, Elizabeth Foster had named her children as Eleanor S. Foster, Susannah M. Foster, and Hester A. Foster. She noted that the other children named in William Foster’s will (Mary Ann and William) had died as “infants” (minors) and unmarried, so she was their next of kin. Sadly, they must have died between 1827 and 1835.

Nowhere in any of the lawsuit documents was it mentioned that Elizabeth Foster was a woman of color.

Why did Elizabeth Foster move to Massachusetts, and why did she turn to William Barstow to be her attorney and guardian of her children? William Foster’s direct line had been in Liberty County since the 1750s; however, genealogical records show intermarriage between Fosters and Barstows in Massachusetts dating back to the Mayflower days, and it is likely there was a family connection.

In 1840[27], Elizabeth Foster was listed in the federal census for Rochester as a white head of household with four white children.

Fig 14 Elizabeth Foster in the 1840 census

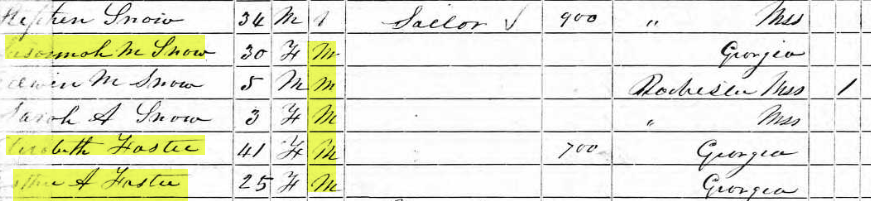

In 1850[28], Elizabeth Foster and her daughter Esther A. Foster, now 25, were still living in Rochester. They were both identified as mulatto, both born in Georgia, and the value of the real estate Elizabeth owned was estimated at $700. She was living near her daughter Susannah, who had married Stephen Snow, a sailor, and their two children, Edwin and Sarah Snow. Susannah and her children were listed as mulatto, but Stephen was not. They were living in a neighborhood of white tradesmen – ships carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers – and sailors, including a number of Barstow families.

Fig 15 Elizabeth Foster in the 1850 census

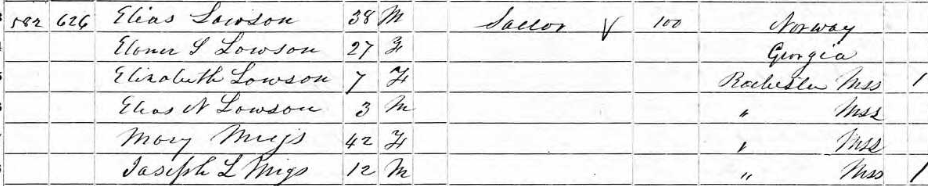

Daughter Eleanor was also in Rochester in 1850[29], but was living with her husband, Elias Lawson, and their children Elizabeth and Elias. Their race was not listed, indicating that they were perceived as being white. Elias was a sailor born in Norway.

Fig 16 Eleanor and Elias Lawson in the 1850 census

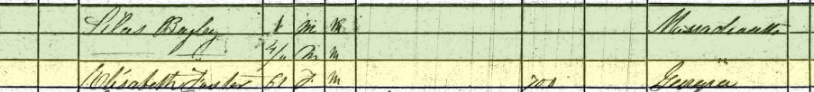

By 1860[30], Elizabeth Foster, still listed as mulatto, was listing with daughter Ester and her husband Silas W. Braley. Braley’s race was not listed, indicating he was white, but Ester, and her two oldest children, Gertrude and Russell, were listed as black, and two younger children, Silas and an unnamed infant, were listed as mulatto. Silas Bayley was also a ship’s carpenter, and the neighborhood was still occupied by white tradesmen and seafarers.

Fig 17 Elizabeth Foster in the 1860 census

In the 1865[31] Massachusetts state census, Elizabeth Foster, still listed as mulatto, was living with the Harvey Snow family in Rochester.

Her daughter Susannah and husband Stephen Snow moved to Port Orange, Volusia, Florida between 1865 and 1870[32].

In 1870[33], Elizabeth Foster was living by herself in Mattapoisett. She had real estate valued at $500 and her personal estate was valued at $200.

![]()

Fig 18 Elizabeth Foster in the 1870 census

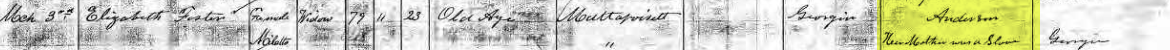

Elizabeth Anderson Foster died shortly before her 80th birthday in Mattaposett, Massachusetts on March 3, 1878[34]. Her father was listed as “Anderson” and where her mother’s name should have been listed was the notation “Her Mother was a Slave,” born in Georgia.

Fig 19 Elizabeth Anderson Foster’s death record, 1878

Elizabeth Foster’s daughters married men with extensive family connections in Mattapoisett, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, and had children of their own. Eleanor’s children all died young, but Susannah and Ester all had grandchildren who were listed as “white” in census and other records. Their descendants may not know of their ancestor Elizabeth Anderson Foster’s complex family history.

Endnotes

- Liberty County, Georgia, Court of Ordinary Marriages White & Colored, Book A, 1819-1896, Index Section “F” (by men’s names), William Foster to Miss Elizabeth Anderson, Liberty County, Georgia, Feby 17, 1818, by John Stewart, Esqr. Digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed 5/16/2022): “Georgia, Marriage Records From Select Counties, 1828-1978,” -> “Liberty” -> “Marriages (White and Colored), Book A, 1819-1896.” ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book H (1816-1822), p. 323-5. Image #194-5 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSTD-M?i=193&cat=292358) ↑

- No manumission records for Elizabeth Anderson were found, and it is noteworthy that she was referred to as a “young woman of color,” not as a “free woman of color.” ↑

- Slave Laws of Georgia, 1755-1860, PDF from the Georgia Archives. Also, timeline created by Tara D. Fields in 2004, referring to pertinent Georgia laws: http://www.glynngen.com/enslavement/slavelaw.htm. ↑

- She could only have been free if she was born to a free mother, and if she had been manumitted. Her death registry information indicates that she was born to an enslaved woman, and no records of a manumission was found. ↑

- For documentation of Joseph Hargreaves’ will and the aftermath, search for “Joseph Hargreaves” on the website https://theyhadnames.net/. ↑

- For more about Henrietta Hamilton’s life, see https://theyhadnames.net/2021/06/14/henrietta-hamilton-free-woman-of-color/. ↑

- For documentation, see https://theyhadnames.net/category/free-persons-of-color/. ↑

- All references to Midway Church membership are from History and Published Records of the Midway Congregational Church, Liberty County, Georgia, by James Stacy, published 2002 by The Reprint Company, Publishers. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L93L-PTX?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 180 of 689 ↑

- 1820 U S Census; Census Place: Liberty, Georgia; Page: 314; NARA Roll: M33_8; Image: 249. William Foster family. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book H (1816-1822), p. 136-7. Image #98 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SST1-S?i=97&cat=292358). See abstract at: https://theyhadnames.net/2022/05/03/bill-of-sale-mell-foster/ ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book H (1816-1822), p. 136-7. Image #98 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SST1-S?i=97&cat=292358). See abstract at https://theyhadnames.net/2022/05/03/bill-of-sale-mell-foster/ ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-893L-GHP5?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 610 of 689. See abstract at https://theyhadnames.net/2018/10/29/liberty-county-estate-inventory-division-jonathan-bacon/ ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. H-I 1816-1831,” Record Book H (1816-1822), p. 341-2. Image #203-4 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS42-SSRB-7?i=202&cat=292358) ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-893L-GCQ1?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 447 of 689. See abstract at https://theyhadnames.net/2018/07/06/liberty-county-estate-inventory-william-anderson/. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, pp. 227-8. Image #155-6 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T9KZ-X?cat=292358). See abstract at https://theyhadnames.net/2020/03/13/liberty-county-estate-inventory-division-william-anderson/. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, pp. 372-3. Image #237-8 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T925-4?i=236&cat=292358]. See abstract at https://theyhadnames.net/2020/03/13/liberty-county-estate-inventory-division-william-anderson-2/. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93L-GHGD?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 682 of 689. See abstract at https://theyhadnames.net/2018/09/09/liberty-county-estate-division-william-anderson/. ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9Q4-ZS8D?cc=1999178&wc=9SBV-C6D%3A267679901%2C267957201 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Estates 1775-1892 Dunham, William-Fraser, Abram > image 1137 of 1188, Last will and testament of William Foster. Abstract at: https://theyhadnames.net/2022/05/09/liberty-county-will-william-foster/ ↑

- “Georgia Probate Records, 1742-1990,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-893L-PQB?cc=1999178&wc=9SYT-PT5%3A267679901%2C268032901 : 20 May 2014), Liberty > Wills, appraisements and bonds 1790-1850 vol B > image 456 of 689. See abstract at https://theyhadnames.net/2019/07/28/liberty-county-estate-inventory-william-foster/. ↑

- 1830 United States Federal Census, Census Place: Rochester, Plymouth, Massachusetts; Series: M19; Roll: 64; Page: 289; Family History Library Film: 0337922. Elizabeth Anderson. Viewed at Ancestry.com (accessed 5/16/2022). https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8058/images/4411352_00581?pId=2007568. ↑

- Family Search.org. Liberty County Superior Court “Deeds and mortgages, 1777-1920; general index to deeds and mortgages, 1777-1958,” Film: Deeds & Mortgages, v. K-L 1831-1842,” Record Book K, 1831-1838, pp. 225. Image #153 (Link: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-T9L4-2?cat=292358 ↑

- To research the individuals not sold to William Jones, please see Moses L. Jones’ 1851 estate inventory (and succeeding inventories on the TheyHadNames.net website): https://theyhadnames.net/2019/09/08/liberty-county-estate-inventory-mary-l-jones/. ↑

- For more information on the enslaved people sold to William Jones, see: https://theyhadnames.net/2021/04/27/list-of-enslaved-people-belonging-to-william-jones-1802-1885/. ↑

- Proceedings of the Liberty County Superior Court, 1835. FamilySearch.org, Liberty County Superior Court Proceedings, Vol. 4 1833-1840. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3H3-Q587?i=124&cat=293357. ↑

- 1840 federal census for Rochester, Plymouth County, Massachusetts. Elizabeth Foster. Accessed at Ancestry on 5/16/2022 (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8057/images/4409451_00564). ↑

- 1850 United States Federal Census, Rochester, Plymouth, Massachusetts; Roll: 333; Page: 288a. Accessed at Ancestry.com on 5/16/2022 (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8054/images/4181058_00580?pId=10462969). ↑

- 1850 United States Federal Census, Rochester, Plymouth, Massachusetts; Roll: 333; Page: 294a. Accessed at Ancestry.com on 5/16/2022 (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8054/images/4181058_00592?pId=10463451) ↑

- 1860 United States Federal Census, Mattapoisett, Plymouth, Massachusetts; Roll: M653_519; Page: 400; Family History Library Film: 803519. Accessed at Ancestry.com on 5/16/2022 (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7667/images/4232248_00399?pId=9673326). ↑

- Massachusetts, U.S., State Census, 1865, Mattapoisett, Plymouth County, p. 36. Accessed at Ancestry.com on 5/16/2022 (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9203/images/41265_316188-00075?pId=3645027). ↑

- 1870 United States Federal Census, Subdivision 17, Volusia, Florida; Roll: M593_133; Page: 733A. Accessed at Ancestry.com on 5/16/2022 (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7163/images/4263359_00601?pId=13911324). ↑

- 1870 United States Federal Census, Mattapoisett, Plymouth, Massachusetts; Roll: M593_639; Page: 427B. Accessed at Ancestry.com on 5/16/2022 (https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7163/images/4271390_00023?pId=25829200). ↑

- Massachusetts, Death Records, 1841-1915, Ancestry.com. (Accessed on 5/16/2022; https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2101/images/41262_b139264-00287?pId=1131574) ↑